In this Edition:

A look back at key regulatory changes and proposals in 2015 and a look ahead at 2016 for mutual funds, hedge funds, and private investments.

- Mutual fund regulations hone in on systematic risk, targeting money market funds, liquidity, and use of derivatives

- Market conditions and regulations present opportunities, test skill of hedge fund managers

- Private equity firms adjusting to new levels of regulatory scrutiny

Mutual Funds

Money funds, liquidity, and use of derivatives areas of regulator focus

Mutual funds and their advisors, already highly regulated, were affected by several broad-based regulatory initiatives last year. In early 2015, the industry focused on the probability of large fund companies being named “systemically important non-bank financial institutions,” and thus subject to an even higher level of regulatory scrutiny. US regulators then shifted their efforts to address systemic risks away from a company-based approach and toward an activities-based approach. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed several regulations over the year (and in 2014 as well) to address what it views as significant risk factors in the mutual fund industry: money market fund reform, liquidity of mutual funds, and, most recently, use of derivatives.

See, for example, the November 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update

US money market mutual fund reforms are furthest along, with new rules taking effect in October 2016 that will mark a significant shift in the institutional money fund market. Among the changes: only “government” institutional money funds will be allowed to maintain a $1.00/share net asset value (NAV). While it is difficult to say how much of the market will shift to government-only products, this shift is coming at a time when the supply of Treasury bills (relative to total Treasuries outstanding) is at a “multi-decade low,” according to the US Treasury. As we have noted in the past, it is unclear whether this regulatory change (along with a host of others that rely on high quality collateral) will have an impact on the short end of the Treasury market. However, in response to low supply and in acknowledgement that demand for T-bills is high and likely to grow, the US Treasury recently announced it will change its issuance pattern in favor of increased T-bill issuance. Over the next quarter, the Treasury Department expects to decrease nominal coupon security issuance by $12 billion in favor of T-bills. The department has also signaled that it may do more of this going forward.

See November 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on this topic.

In September 2015, the SEC floated a proposal to require mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) to take a more formalized approach to liquidity management. The Commission’s proposal included establishing liquidity-related policies, as well as a portfolio-level requirement that funds maintain sufficient liquidity while taking into account fund-specific characteristics (e.g., fund investment types and shareholder base). As if on cue, Third Avenue Focused Credit Fund, a high-yield bond fund, suspended investor redemptions, citing the illiquidity of its distressed bond holdings. While industry participants are still seeking modifications to the proposal, continued illiquidity in the high-yield bond and bank loan markets may serve to strengthen the regulator’s hand.

For more background on alternative mutual funds, please see Sean McLaughlin et al., “Assessing the Liquid Alternatives Landscape,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, March 2015.

Before year-end, the SEC took the next step in its systemic regulatory-focused agenda by proposing a major overhaul of regulations on the use of derivatives by mutual funds and ETFs. Generally, the proposed rules cap funds’ aggregate notional exposure at 150%, with a risk-based portfolio exposure limit of 300% of assets.[1]If a fund can show that derivatives are being used to reduce portfolio risk, the 300% limit applies. While traditional stock and bond mutual funds often reserve the right to use derivatives, most make little use of these financial instruments. However, the proposed changes have the potential to significantly impact more leveraged corners of the fast-growing “alternative” mutual fund segment of the market. The leverage limits may also be a death knell for portions of the nearly $42 billion leveraged ETF market. The SEC’s proposal also requires mutual funds and ETFs to segregate cash and equivalents sufficient to cover their obligations under derivatives contracts on a mark-to-market basis plus a little bit more coverage in case of market stress.[2]The proposed regulations also allow funds to meet coverage obligations by holding the asset that would be deliverable under the derivative contract. This stands to increase the cost to funds of entering into derivatives transactions, and, of course, reduces asset management flexibility in the fund format. Expect the derivatives debate to continue into 2016 as the SEC seeks comments and the industry (inevitably) pushes back. And even as the US regulator proposes leverage limits on ETFs and mutual funds, some jurisdictions are heading in the other direction. Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission just recently announced it would allow leveraged and inverse ETFs in the Hong Kong market. This appears to be in response to the Hong Kong government’s interest in maintaining the competitiveness of its funds market with other regional jurisdictions.

Looking ahead, the SEC plans to continue addressing systemic risks in the asset management market. Expect to see the regulator implement Dodd-Frank mandated stress testing and, potentially, “resolution” plans for failed asset management firms. The SEC’s current activities-based approach to systemic financial regulation of asset managers has bought at least some time for large non-bank asset management firms, but global financial stability regulators such as the Financial Stability Board still appear to be pursuing a company- or fund-based approach. This raises the prospect that within the next several years, large firms may still find themselves subject to “enhanced” regulatory supervision.

Hedge Funds

Regulatory scrutiny creates a tough deal environment while changes to the fixed income and equity markets have an impact on liquidity

See also our Fourth Quarter 2015 Hedge Fund Update for a discussion of recent hedge fund performance and the impact of regulatory issues.

Regulatory developments had a significant impact on hedge funds in 2015 and these trends show no signs of abating. This should benefit managers that can successfully execute their strategy in a more complex environment.

For more see Brett Snidtker et al., “Tough Sailing for Event-Driven Strategies,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, February 12, 2016.

For event-driven hedge funds, 2015 was a challenging year. Several large mergers[3]Among them, Comcast/Time Warner and Applied Materials/Tokyo Electon. broke under regulatory pressure as antitrust authorities increased both the number and duration of investigations. Industry sources estimated that the number of significant merger investigations rose by more than 30% in 2015, and those investigations took about 35% longer than two years ago.[4]Dechert LLP, “Dechert Antitrust Merger Investigation Timing Tracker Reports Record Duration and Number of U.S. Merger Investigations in 2015,” January 2016. Plenty of funds took a performance hit from this shift in the mergers & acquisitions market last year, but this uncertainty has also contributed to spread widening, thus improving return prospects for well-positioned managers.

The distressed markets have also felt the impact of regulatory changes that have been driving banks to hold lower inventories of bonds of all types. Managers have commented that they continue to see very low levels of liquidity in the stressed high-yield and distressed markets. They have also pointed to the greater participation of retail funds and ETFs in the high-yield and loan markets as a factor that could lead to increased price volatility. These funds offer high levels of liquidity to investors and that may make them more liquidity “takers” instead of liquidity “makers” in a stressed market. This is especially important because while banks have retreated, mutual fund and ETF holdings of less liquid credit instruments have exploded since 2008—from an estimated $150 billion to nearly $1 trillion in 2014, making them a major potential source of liquidity in credit markets. Reacting to the possibility of reduced market liquidity and longer holding periods for investments, we have largely seen distressed-focused hedge funds head the other direction, seeking longer lock-ups for capital or more staggered capital bases to give them better staying power. Experienced hedge fund managers have been moving cautiously given uncertainty about how rapidly the distressed pricing observed in the energy sector might spill into other sectors, as well as concerns about market illiquidity given these technical factors.

For more on dark pools, please see the August 2014 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update.

Equity market structure issues continue to have an impact on managers as well. Off-exchange trading remains a significant force in the marketplace, with so-called “dark pools” or alternative trading systems representing an estimated 15% of total US market share in 2015. Billed as an efficient marketplace for institutional traders, dark pools and their operators have taken some knocks lately. In early 2016, Barclays and Credit Suisse agreed to pay a total of $154 million in fines and profit disgorgement over allegations that they misled investors about the operation of their pools. The SEC had already stepped in with a proposal to increase transparency and regulatory oversight of these venues. An additional estimated 20% of US market volume in 2015 was represented by off-exchange trading that took place outside of dark pools. This represents shares traded on single-dealer platforms or internalized at broker-dealers. According to an analysis by Deutsche Bank, this shift to non–dark pool, off-exchange trading creates a market where accessible liquidity can be considerably less than one might expect simply by looking at market volumes. Case in point: according to the Deutsche Bank study, more than 30% of reported trading volume for Apple, Facebook, and Netflix took place in these “inaccessible” venues during 2015. For hedge funds, these market structure issues point to the continued need for excellent execution capabilities and an appreciation for how market structure may affect pricing and available liquidity.

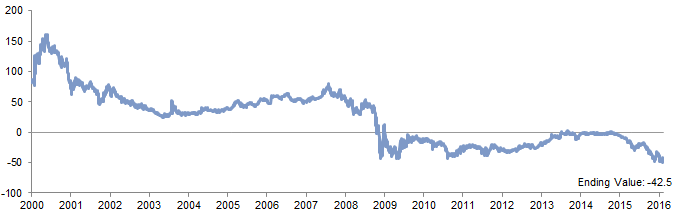

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

Note: Data are daily.

Ongoing and perplexing pricing anomalies between Treasury bonds and swaps referencing Treasuries (“swap spreads”) have been a source of profits or a thorny place to lose money for a number of trading-oriented funds. In effect, the interest rate for swaps on Treasures is now cheaper than for the physical security. The pricing shift first happened in the 2008 period and slowly corrected. However, it moved from the long end of the curve down through shorter maturities during 2015 and into early 2016. Changing bank capital rules, increased (repo) financing costs, corporate debt issuance, pensions’ hunger for duration and sales of cash bonds by massive sovereign wealth funds have been variously thought to be behind the inverted pricing in this market. Is this merely a temporary anomaly or is it paradigm shift? Some managers have already suffered losses betting on a return to historical norms, which would have physical Treasuries trading above swaps. Others have begun to speculate that swaps pricing is a purer reflection of the risk-free rate in the market today and could become the new market benchmark going forward.

See our May 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on swaps regulation.

Looking ahead, many of these market structure and regulatory factors are likely to continue to have an influence on the market environment for hedge fund managers. The increased level of antitrust and other regulatory scrutiny of mergers should support wider deal spreads. Meanwhile, within the stressed high-yield and distressed sectors, technical factors contributing to greater price volatility appear likely to persist. Both factors seem capable of leading to more return differentiation across managers and should have an outsized impact on funds that can operate successfully in a more complex environment. Managers that trade in the swaps market may see the impact of pending regulations governing margin on bespoke swaps. To date, Dodd-Frank driven changes to the swaps market have largely been focused on the standardized, (and now) centrally cleared swaps market. However, nearly 40% of all swaps are not centrally cleared and regulators have been driving toward standardized margin (initial and variation) requirements for this group of contracts. Meanwhile, European authorities are, yet again, trying to move forward with a financial transactions tax and have also begun requiring firms to enhance disclosure and reporting of securities financing transactions such as securities lending and repurchase agreements. These initiatives could also have an impact on managers during 2016 and beyond.

Private Investments

Expense allocation, fees, and valuation practices draw regulatory scrutiny

Private equity firms have not been immune to regulatory change in 2015, both on an organizational level and within their marketplace.

See our May 2014 Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on expense allocation.

As part of US regulatory reforms, buyout managers and private real estate managers were required to register with the SEC and are now subject to a higher level of regulatory scrutiny than in the past. SEC staff initially focused their attention on hedge funds and private equity firms, and by 2015 staff had completed “presence examinations” at about one-quarter of all registered firms. These focused examinations moved regulatory staff up the learning curve, helping them identify key issues within these new cohorts of registrants. Coming out of these early initiatives, SEC staff has focused attention on issues surrounding expense allocation, fee disclosures, and valuation practices. A number of private equity firms have been subject to SEC enforcement action as a result.[5]In mid-2015, KKR paid a $30 million to settle SEC charges that it misallocated broken deal expenses to the detriment of its flagship fund.

For more on this topic, see our May 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update.

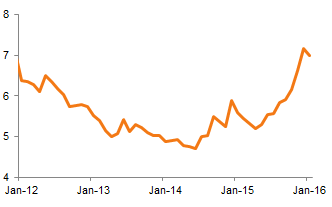

Private equity firms are also facing a tougher deal-financing environment, with regulatory pressures on banks mounting as the credit cycle matures. Beginning in 2013, banking regulators began to urge banks to put the brakes on issuing loans to “highly leveraged” buyouts—those where the company’s debt would exceed 6.0x EDITDA. While deals continued, market commentators began noticing that non-bank credit providers were filling the gap, as they began to provide more financing to leveraged transactions. More recently, the leveraged loan market has been under pressure and several large buyout deals proved difficult to finance. According to press reports, KKR approached more than 20 banks to provide financing for a deal late last year before it finally underwrote the debt itself.[6]Koh Gui Qing and Greg Roumetliotis, “Private Equity Deals Hit as Banks Curb Lending for Leveraged Buyouts,” Reuters News, January 17, 2016. In the meantime these pressures have helped drive up financing costs, with yields on first lien loans moving up considerably as of year-end.

Source: Credit Suisse.

Note: Data are monthly.

Looking ahead, private equity firms’ operations will be under continued scrutiny as regulators and industry develop a shared understanding of acceptable industry norms. The SEC continues to focus on the allocation of fees and expenses among parallel investment vehicles and the payment of fees (for example, accelerated monitoring fees) by portfolio companies to the manager or its affiliates. Given the growing role of co-investments in the private equity market, the regulator has also flagged disclosure of co-investment allocation policies, including arrangements whereby investors have negotiated priority capacity, as an area of ongoing concern. Additionally, recent press reports about potential conflicts of interest from the private equity industry practice of designating counsel to be used by investment banks in loan syndications may also prompt regulatory attention this year. Finally, the SEC’s private funds unit has highlighted concerns around the disclosure by private real estate managers of the provision of real estate management services and staff to fund-owned properties while charging separately for those services.

Footnotes