In this Edition:

- Money market fund reform may require a change in approach to cash management

- Updated FASB fair value guidelines modify disclosure requirements for certain assets

-

A look at Dodd-Frank’s first five years

Money Market Fund Reform

Time to Make the Switch?

A year ago, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted rules that effectively restructured the $3.0 trillion US money market fund industry. These changes, many of which become effective in October 2016, may require institutional investors to make changes to their approach to cash management. While the effective date is more than a year away, we believe affected investors should source vehicles sooner rather than later.

Money market fund reform was driven by regulators’ desire to reduce sources of systemic risk in an effort to bolster the resiliency of the financial markets. Regulators pointed to the capital markets impact of large outflows from institutional prime money funds during the credit crisis and noted that investors appeared to be motivated by a perceived “first mover advantage” in redeeming from riskier (prime) cash vehicles.

Historically, US money market funds have been permitted to use amortized cost accounting and other techniques to maintain a value of $1.00/share. In its most recent round of reforms, the SEC focused on this stable share price feature as a reason for shareholder “runs on the bank.” Why? If the underlying net asset value (NAV) of a fund diverges too much from its $1.00 share price in a market drawdown, funds may “break the buck” and pay out shareholders at less than the expected $1.00/share. In fact, the SEC noted that there have been numerous instances of fund sponsors “bridging the gap” through cash infusions to avoid this outcome.

For further discussion, please see the November 2014 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update.

The structural changes included in the 2014 money market fund reforms seek to improve market stability in two ways: (1) eliminate the $1.00/share NAV standard for institutional prime money market funds, and (2) establish a framework for implementing gates or redemption fees in some classes of (non-government) money market funds. Going forward, government funds will be the only type of money market fund available to institutional investors seeking stable NAV funds.[1]Per the SEC, government money market funds must now have 99.5% or more of total assets invested in cash, government securities, or repurchase agreements collateralized by cash or government … Continue reading Institutional prime money market funds will go to a floating NAV structure and be subject to the new redemption fee and gate framework.

What amount of assets could shift from institutional prime funds to government funds as the October 2016 effective date nears? According to the SEC, more than $1.2 trillion (about 40% of the money market fund market) are invested in institutional prime money market funds. Consensus is that a significant portion of these assets could move to institutional government money market funds in response to the new regulations, with several pre-reform surveys indicating that more than 75% of polled investors would reduce or eliminate investments in floating NAV funds. That implies the potential for up to $900 billion in demand for government-only money market funds.

Could investor shifts from institutional prime money market funds push down yields on government securities or swamp the existing supply of institutional government money funds? Pre-reform, SEC estimates were that Treasury debt and repurchase agreements held by all money market funds (retail and institutional combined) amounted to approximately 45% of the available supply of Treasury bills and repurchase agreements. The prospect of adding significant new demand on top of that sounds worrisome. However, institutional government money funds are not restricted to only holding Treasuries, and by some estimates eligible government securities (including Treasuries) total between $5.2 trillion and $6.8 trillion. By itself, this reform is unlikely to cause a supply/demand imbalance, but investors should also consider that other regulatory shifts (derivatives reforms among them) appear to lean heavily on high-quality collateral as a problem solver. In aggregate, the SEC has acknowledged the possibility that its reforms could drive down yields for government securities—delicately referring to this potential outcome as “lowering borrowing costs.”

Predictably, investment managers have been rolling out new products and reconfiguring existing money market funds in response to the pending regulations. There has been a pronounced uptick in “ultra-short” funds coming into the market, often looking like floating NAV retreads of “enhanced cash” funds. Our Manager Research Team has engaged with a number of cash managers since the reforms were announced to gauge the impact of these regulatory changes. While the extraordinary short-term cash flows into government and Treasury money funds in September and October 2008 may not be poised to repeat, managers have been willing to close money market funds in the face of strong investor flows.[2]According to the SEC, $409 billion flowed into government and Treasury money funds during a five-week period in September/October, 2008. This has especially been the case when managers perceived that flows would potentially drive down fund yields. We remain concerned that if investors in institutional prime money market funds wait until 2016 to source a stable NAV fund, they may have limited choices.

FASB Change to “Fair Value Measurement” Standards

Not Quite Regulation, but We Thought You Might Ask . . .

For many of you, ’tis the season—the summer picnic and barbeque season? No—the audit season, at least for those many institutions with June 30 fiscal year ends. So, in the spirit of the season, we thought we’d diverge from focusing strictly on regulations and spread some cheer (?) in the form of a recent (May 2015) change to the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB) Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 820 Fair Value Measurement Standards. ASC 820 is the standard that brought investors “Level 1,” “Level 2,” and “Level 3” investments.[3]The fair value levels run from Level 1 (most transparent and verifiable valuation) to Level 3 (least verifiable valuation inputs), as defined by FASB in ASC 820. Essentially, the ASC requires organizations to characterize the fair value of their investments based upon either the observability of pricing inputs or using reported NAV as a “practical expedient.”[4]According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, for investments such as publicly traded mutual funds, a publicly quoted NAV is the fair value, and is not treated as a “practical expedient.” These amendments … Continue reading Investments measured using NAV as a practical expedient must then be leveled based on characteristics such as redemption terms. Simply put, the intention of this structure is to provide information on both the value of investment assets and the likelihood that an entity would actually receive the reported fair value of assets if it attempted to liquidate to cash.

One unforeseen challenge with applying ASC 820 has been that in some cases, funds with portfolios comprising long-only, publicly listed securities are being characterized as “Level 3” investments (basically, illiquid and leveled alongside private equity funds) if they offer only quarterly liquidity. In adopting these amendments, FASB recognized that reporting entities have taken different approaches to leveling assets in funds with periodic liquidity—particularly those that sit between daily priced funds and private equity–style investments with no redemption provisions. This weakens the usefulness of the leveling system. The amendments to ASC 820 move away from leveling assets where reporting entities are using NAV as a practical expedient.

Going forward, assets valued using NAV as a practical expedient will be reported separately from the fair value hierarchy. In addition, reporting entities must disclose the nature and characteristics of investments held outside the fair value framework. Examples of the types of information to be disclosed include: investment category and description, liquidity periodicity, and notice period.[5]See page 10 of the FASB release for a more detailed example. Investments that continue to be included in the fair value hierarchy will not be subject to the same disclosure requirements. These changes should improve disclosure regarding the nature of investments held and also simplify leveling decisions. The amendments have a rolling effective date beginning in December 2015, though early adoption of the amendments is permitted.

“Happy” Birthday?

Dodd Frank Turns Five . . .

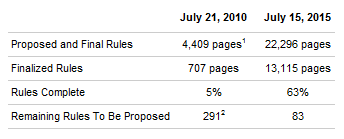

US landmark financial legislation The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank) celebrated its fifth birthday in July. Yet despite the fact that Dodd-Frank has been the law of the land for five years, substantial portions of its enacting regulations are not finalized (15%) or not yet proposed (21%). While Dodd-Frank’s impact will continue to unfold in the years ahead, it has already been a driving force for a series of significant changes to the asset management business and investment markets. Below are some of the major changes already underway and those that are yet to come.

Source: Davis Polk & Wardell LLP., Wall Street Journal.

¹ At the end of the first year.

² As of March 31, 2011.

More regulation of alternative funds. Alternative funds—hedge funds, private equity, and private real estate funds (but not venture capital)—are much more regulated today than five years ago. Managers of these types of funds must now register with the SEC.[6]Note that SEC registration requirements are subject to asset size thresholds. Even if they do not manage publicly traded mutual funds, private fund managers must now report detailed information about assets, investment strategies, investment holdings, leverage levels, and counterparty exposure to the SEC on a periodic basis via the newly implemented Form PF. Private funds of all types are under much greater regulatory scrutiny today, and SEC examinations of these newer registrants have led to a string of enforcement actions. Not unexpectedly, the internal infrastructure changes and additional staff needed to comply with a new regulatory structure have driven up costs for these managers.

For more on this, please see the February 2015 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update.

The end of proprietary trading. Although barriers to entry (in the form of costs) for private funds have increased, a steady stream of private investment teams have exited banks over the last five years. Dodd-Frank’s Volcker Rule prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading in many types of assets. The Volcker Rule also restricts banks’ ability to hold positions in private equity funds. While the Rule just became effective in July 2015, affected banks and bank employees have been restructuring or spinning out groups since shortly after the legislation was finalized. Volcker Rule compliance has also driven secondary market sales of bank private equity portfolios.

Volatility continues even if “systemic” risks are now a regulatory focus. Five years in, it is clear that the Volcker Rule (and Dodd-Frank more broadly) won’t prevent banks from incurring large trading-related losses. Witness the estimated $6.2 billion loss incurred by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. in the “London Whale” episode in 2012, for example. Or, more recently, the $150 million in losses posted by Citi and $300 million in gains posted by J.P. Morgan when the Swiss Central Bank decided to unpeg the value of the Swiss franc. While the law did create a structure to reduce systemic risks to the financial system, the last five years have not lacked drama, as evidenced by the 2010 “Flash Crash,” the 2011 trading-driven bankruptcy of MF Global, and the 2012 software bug that took down market-maker Knight Capital.

Effects on a wide range of markets. Dodd-Frank has had other impacts on the investment markets. The US law and pending Basel III Capital Requirements are often the “usual suspects” blamed for well-documented declines in dealer inventories of fixed income instruments. A totally new regulatory structure has been constructed around the over-the-counter derivatives markets, with some market participants (municipalities and other “special entities”) finding it harder to access the market and costs (including margin) going up for other participants. Banks have apparently unloaded some of their private equity portfolios on the secondary market, but ebullient market conditions and continued investor enthusiasm appear to have bailed them out, as secondary market pricing has not approached distressed levels. These impacts are just the tip of the iceberg as Dodd-Frank and other legislation come into effect.

More still to come. We continue to assess the impact of these legislative changes on the markets. Market inefficiencies driven by Dodd-Frank and other post-crisis regulations may increase the possibility of price dislocations that hedge funds and less constrained investors can take advantage of. Higher barriers to entry in the private investments space and less leveraged capital in the system (in the form of proprietary trading desks) may improve the prospects for some investment strategies over time. Changes to the collateralized loan markets are still underway and may create some opportunities. The introduction of central clearing for over-the-counter derivatives has encouraged a move toward “futurization” in the derivatives markets and spawned new types of instruments that are intended to have a lower implementation costs. And while regulators continue to grapple with the “shadow banking” market, they are in some cases trying to encourage alternative lending channels to support credit needs in the real economy. In sum, five years in the long-term impacts of Dodd-Frank are still unfolding and will undoubtedly provide opportunities for flexible investors along the way. ■

Footnotes