In This Edition

- Banking regulations continue to impact hedge funds

- FSOC moves forward in identifying systemically important financial institutions

- SEC’s 2014 report provides insight on trends in alternative funds

- FATCA implementation continues

Assessing the Evolving Impact of Banking Regulation on Hedge Funds

Hedge funds’ relationships with prime brokers unstable due to new regulations

While increased regulation in the post–financial crisis era has directly affected hedge funds, shifts in banking regulations that affect the prime broker (PB) business model are also increasingly impacting funds. Our discussions with funds and PBs have made apparent that implementation of Basel III (an international regulatory framework for banks) is changing the way funds interact with PBs and how PBs assess their relationships with funds. As some in the industry predicted, PBs are in some cases terminating relationships with hedge funds, citing increased capital costs of doing business. This has fueled concerns that less readily available PB support will increase the barriers to entry and break-even costs for smaller and start-up funds.

Our business risk management group recently met with a number of PBs to discuss the current market environment and its impact on their businesses. From those conversations and our discussions with managers, several trends emerge: (1) banks and, by extension, PBs are much more focused on the “balance sheet cost” of their relationships with hedge funds than in the past; (2) funds must be much more cognizant of the way they allocate balances across their relationships; (3) the prospect of increased costs has caused some behavioral shifts at hedge funds; and (4) increased pricing transparency is helping funds and brokers rationalize their relationships.

Banks increasingly assess their relationships in terms of the regulatory capital cost of the services they provide. This includes the extension of credit to funds, the type of financing the banks provide, and the duration of financing. Rather than simply assessing the overall size of the relationship and level of activity, banks have become more focused on the mix of services they provide to funds and on ensuring they make efficient use of balance sheet cost. In addition, banks are looking across their enterprise to assess the overall economics of a relationship with a firm.

In response to this shift in the PB business model, hedge fund managers are more focused on the amount and types of balances they have with individual PBs. For example, managers place greater emphasis on having both long and short balances with brokers to reduce the capital cost of the relationship. In addition, brokers are providing feedback to funds on alternative ways to structure investment exposures to reduce the express or implied costs of the positions.

Looking forward, our discussions with funds and PBs suggest further ways that fund managers will likely change their operations. While many fund managers moved toward having multiple PBs after the financial crisis, a consolidation of balances with two or perhaps three PBs looks to be the trend. This allows funds to better manage their balances and increase the overall size of their relationship with individual PBs while also maintaining some level of counterparty diversification. Some managers are now willing to engage in securities lending as a way to offset internal costs. Others have revisited allowing “rehypothecation” of fund assets, the practice of permitting PBs to use hedge fund assets posted as collateral for their own collateral needs. Market participants have noted that firms permitting rehypothecation today receive much more transparency than in the past, which helps them better assess the risks of the activity. Similarly, funds have noted that services today can supply much better transparency into security borrowing costs, which has helped improve managers’ ability to assess the economics of balances with their PBs.

Taken together, these changes put even more emphasis on fund’s ability to effectively manage operational and treasury functions. As banks continue to refine their approach to the cost of providing PB services to funds, some funds will likely see their financing costs rise significantly. This will either put pressure on their strategy or require managers to be creative in finding cost-effective ways to execute in a new environment. Finally, as funds seek ways to reimagine their relationships with PBs, investors should focus on whether those shifts are likely to erode returns or increase the risk level of the fund.

The Debate on Defining “Systemically Important” in the Asset Management Industry Continues

Greater reporting burdens on the horizon for asset managers

US super regulator the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC or Council) has been charged with identifying systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, SIFIs are subject to “enhanced prudential oversight” by the Federal Reserve and additional capital requirements. The FSOC started off by designating large banks and several large insurance companies as SIFIs. Over the past year, the Council has struggled with how to assess and reduce the systemic risks associated with the asset management business.

Please see Stephen Saint-Leger, “How Should Investors Respond to the SEC’s New Regulations Governing Money Market Funds?,” C|A Answers, Cambridge Associates, August 5, 2014.

In 2012 the FSOC stepped into the debate on money market fund (MMF) reform. After the SEC failed to vote on a series of MMF reforms, the Council threatened to take up the issue itself. The MMF reform issue eventually resolved itself with the SEC passing a series of changes to MMF structure that are largely due to take effect in 2016.

Next, the FSOC trained its sights on the largest non-bank investment management firms. In a broadly criticized report[1]Please see Emily Stephenson and Sarah Lynch, “U.S. Senators Slam Study on Systemic Risks Posed by Asset Managers,” Reuters, January 24, 2014, for an example of the controversy. from FSOC’s research and data arm, the Office of Financial Research (OFR) attempted to link the largest asset management firms—most of which are associated with mutual funds and ETF markets (Figure 1)—with systemic financial market risks. Based on robust feedback from the industry, the FSOC has pivoted and is now refocusing on the impact of particular products and activities on the financial system. Today, the regulator is looking more closely at investment vehicles as potential transmitters of risk—this includes consideration of liquidity risks and first mover advantages for those redeeming in stressed market periods. Specific types of investments or approaches are also under scrutiny, including the use of securities lending in funds, derivatives use for both registered and un-registered funds, and the “L” word—in this case, leverage. Finally, and taking a page from banking regulation, the FSOC is also focusing on issues arising from the failure of an asset manager.

Source: Towers Watson.

The SEC has since stepped in and announced that it would be focusing on improving its risk monitoring activities and on ensuring that registered funds have appropriate risk controls to address liquidity and portfolio-level risks. The SEC also intends to look at requiring resolution plans for large managers and annual stress testing for large managers and large funds. These initiatives mirror the FSOC’s focus, though they are said to be “complementary” efforts.[2]Mary Jo White, “Enhancing Risk Monitoring and Regulatory Safeguards for the Asset Management Industry,” speech at the New York Times DealBook Opportunities for Tomorrow Conference, New York, NY, … Continue reading

Taken together, there seems to be no question that managers will find themselves with even greater reporting burdens than in the past. Taking MMF reforms as a blueprint, one must also wonder whether regulators will be looking more critically at the risk exposures of US mutual funds in light of their mandate to provide shareholders with daily liquidity. In addition, the FSOC’s focus on leverage and financing exposures instead of asset manager size may lead it to look more critically at the risks posed by some private fund (e.g., hedge fund) managers. Firms that employ significant levels of leverage despite more modest levels of capital under management may find themselves under greater scrutiny going forward. Like the changes in the PB market, this debate bears watching as it is yet another factor that could have an impact on return prospects for funds going forward.

Taking a Second Look at the Alternative Funds Industry

Form PF report provides insight into trends in private funds

As required by the Dodd-Frank Act, private funds (including hedge funds, unregistered liquidity pools, and private equity firms) must report data to US regulators on Form PF.[3]Investment advisers with at least $150 million in private fund assets must file Form PF. One purpose of Form PF is to provide information to assist the FSOC in assessing systemic risks. The information is also playing a role in SEC enforcement activities, with the regulator looking to manager-specific filings and aggregated data to better target enforcement resources. While data filed on Form PF are not available to the public, SEC staff prepares an annual report to Congress regarding Form PF, and this provides a look at trends in the private fund industry.

The 2014 report[4]Please see the “Annual Staff Report Relating to the Use of Data Collected from Private Fund Systemic Risk Reports,” Securities and Exchange Commission, August 15, 2014. on Form PF provides some interesting detail on the growth and continued concentration of the private funds industry. This reflects data from the second full year of Form PF reporting and so some comparisons can be made to assess industry trends.

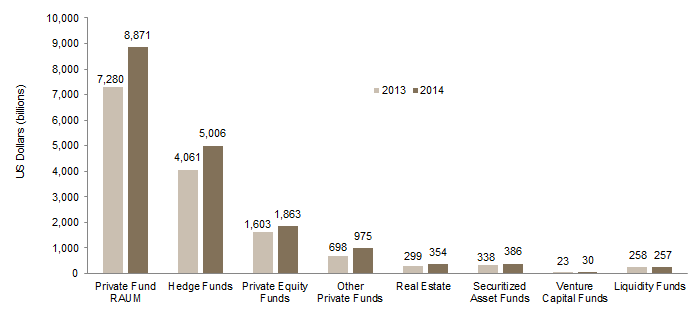

According to the SEC staff report, more than 2,600 advisers filing Form PF managed more than 21,500 funds representing $8.871 trillion in regulatory assets under management (RAUM).[5]RAUM are the gross value of assets, and in the case of private equity funds include unfunded commitments. This places the private funds industry at just over half the size of the US mutual fund industry[6]According to the Investment Company Institute’s Investment Company Factbook from May 14, 2014, the North American mutual fund industry had $15 trillion under management while $30.0 trillion was … Continue reading and represents an increase of more than $1 trillion in RAUM over 2013 Form PF Report levels (Figure 2).

Source: US Securities and Exchange Commission.

Assets remain significantly concentrated in the largest funds. This year, more than 6,400 hedge funds with RAUM under $500 million reported to the SEC. These represented only 19% of hedge fund assets while 1,326 larger funds (only 17% by number of the funds reporting) represented 81% of RAUM (Figure 3).

Source: US Securities and Exchange Commission.

Notes: The SEC considers a hedge fund to have a net asset value of at least $500 million. Large funds are larger than $500 mm.

FATCA Spreads to the Rest of the World

Steam builds as countries announce information-sharing initiatives

With implementation of the US Foreign Account Tax and Compliance Act (FATCA) finally underway, efforts to replicate the law’s emphasis on cross-border information sharing have gained steam. While FATCA became law in 2010, it has proven complex to implement and consequently has been subject to a number of delays. During 2014, FATCA-compliant financial institutions began to adopt and implement new FATCA-compliant account opening procedures. Beginning at year-end 2014 and extending into 2016, institutions are engaged in meeting phased-in requirements to complete due diligence on existing account holders. For many investors, this means a new round of requests for updated US tax documents, whether Form W-9, W-8, or W-8-BEN-E. In some cases, investment managers’ administrators appear to be sending all possible forms to investors in an effort to “cover the waterfront,” an approach that may lead to more investor confusion and less ready compliance. Even as they deal with the demands of the initial implementation phase of FATCA, investors should be aware that other multi-jurisdictional tax information sharing initiatives could result in further documentary demands through 2017.

For more on FATCA, please see Mary Cove, “Quarterly Regulatory Update,” Cambridge Associates LLC, May and August 2014 editions.

What is FATCA? FATCA seeks to reduce tax evasion by identifying and gathering information on US taxpayers that hold non-US accounts. This US law requires foreign financial institutions to agree to a series of reporting, account due diligence, and withholding requirements in an effort to improve tax collection efforts. Since some nations’ privacy laws do not permit financial institutions to share client data other than with the home country, FATCA implementation has been challenging. In response, nearly 100 jurisdictions have reached an agreement (or an agreement in substance) to receive information from local financial institutions and share it with US tax authorities. Further, some countries have established reciprocal agreements with the United States—which means that the United States will be sending foreign account holder information to participating jurisdictions.

While the United States has been attempting to iron out FATCA implementation, a number of other countries announced initiatives to allow for cross-border sharing of tax information. This effort gained significant traction in October 2014, when the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) announced that more than 50 jurisdictions had reached an agreement to share tax information with other members of the group. This initiative, sometimes referred to as “GATCA,” is expected to be implemented by 2017. While the OECD released details about a “common reporting standard” for tax information earlier in 2014, questions remain about how to integrate this reporting regime with FATCA. In the meantime, investors should expect that non-US financial institutions may begin another round of data gathering—just as soon as they are set with FATCA.

Footnotes