We retain our overweight to Japanese stocks, but are watching closely to ensure economic or political events do not undermine the promising case for company fundamentals

- Japanese equities have had a particularly poor start to 2016, as concerns mount that slower economic growth and renewed yen strength will weigh on company profits.

- Recent economic data actually look reasonable in the context of long-term trends in Japan; some of the optimistic case for inflation and growth may have been oversold.

- The risk of policy missteps is rising, and the Bank of Japan’s surprise move to negative interest rates has raised questions given implications for savers and financial institutions.

- More important for investors are improvements in corporate governance and a renewed focus on profitability that together are leading to rising earnings and distributions.

- Yen strength and negative interest rates are headwinds, though current valuations offer a cushion; small and domestic-focused companies should be more insulated.

Japanese equities have suffered a rough start to the year—despite a rally in recent weeks, the MSCI Japan was still down around 12% year-to-date through April 15. Recent Japanese economic data have been uninspiring, and the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) surprise decision to adopt negative interest rates at the end of January suggested to some that things may be taking a turn for the worse. Recent yen strength has left many investors feeling nervous about earnings prospects, and foreign investors in particular are heading for the exits. We believe investors should look beyond the recent economic softness and focus instead on what Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s package of economic policies and structural reforms (aka Abenomics) are doing for profits. Index earnings have soared and earnings growth should again outpace that of global peers in the upcoming fiscal year. Given that relative valuations have improved further, we retain our overweight to Japanese stocks versus US equivalents, but are watching closely to ensure the stronger yen and growing disenchantment with Abe’s policies do not jeopardize recent improvements in company fundamentals.

Recent Economic Data Have Been Soft, But Context Is Required

A principal goal of Abenomics was to spur a virtuous cycle where the anticipation of faster growth and inflation would lead to increased spending, spurring an increase in corporate profits that would then be shared with workers, giving the spending boom a second leg. Several initiatives were rolled out to jump-start the cycle and boost corporate profits, including corporate tax cuts and aggressive monetary policy that devalued the yen. Lackluster wage growth during the second half of 2015 and limited inflationary pressures have raised fears that this positive feedback loop has been interrupted or even broken, and new challenges such as ultra-low interest rates and the stronger yen threaten to depress corporate profits. Recent economic data do raise questions about the efficacy of some aspects of Abenomics, but context is required, and the government retains some options.

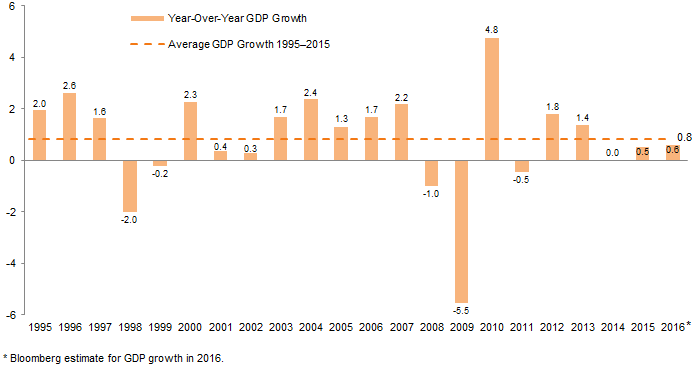

Japanese economic data have recently been a touch weaker; a small contraction in the fourth quarter suggests that 2015 (calendar year) GDP growth will come in at just 0.5%. Exports (around 18% of GDP) and consumption (another 60% of GDP) both shrank during the last quarter of 2015 due to a variety of forces including weakness in China (for the former) and concern over stagnant incomes (for the latter). Analysts believe this weakness may spill over into the first quarter and expect only 0.6% growth in calendar year 2016; the International Monetary Fund recently stated that growth could be even slower (0.5%). These rates of growth are unspectacular on an absolute basis but represent an improvement since Abenomics first came into effect during the recession. Expectations for a sharp growth bounce may also have been unrealistic given longer-term trends; the economy has only grown on average 0.8% per annum since 1995 (Figure 1). Japan’s shrinking population and thus workforce recently caused the BOJ to suggest the long-term potential growth rate for the country is just 0.5%. Generating growth by boosting the share of women in the workforce has seen some success, though encouraging more skilled worker immigration has seen limited progress.

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

Healthier wage growth would support stronger consumption. News that nominal wages in February increased by around 0.9% year-over-year (adjusted for inflation the increase was around 0.4%) was greeted with a sigh of relief given wages stagnated as 2015 drew to a close. The 3.3% unemployment rate might suggest that labor tightness could put upward pressure on salaries, but this statistic ignores a couple of dynamics. Many Japanese firms have large numbers of staff that receive relatively generous seniority-based pay, and thus are especially loathe to increase wages absent any commensurate increase in productivity. Companies with profits that are sensitive to the stronger currency (e.g., automakers) or negative rates (e.g., banks) are also proving especially resistant to demands for wage increases; the annual “shunto” (spring wage negotiations between the unions and large companies) suggests wage growth will be limited in 2016. It is not all bad news for Japanese workers. Large companies may be more generous than smaller peers, and white collar executives may fare especially well. According to research firm GaveKal, finance salaries in Tokyo have increased around 10% over the past year, with bilingual employees seeing even bigger increases. Whatever the outcome of current negotiations, even a slight increase in nominal wages will look favorable relative to the stagnation in 2015 and negative trend when Abe returned to office (adjusted for inflation, wages have been shrinking for years).

The goal of generating 2% inflation also seems a stretch given aging demographics and long-term price trends in Japan. Core consumer price inflation has averaged 0.2% over the past 25 years, and prices were actually declining for most of the five years before Abe came to power. Recently released figures that indicate the BOJ’s preferred measure of core inflation (consumer prices ex food and energy) increased 0.8% year-over-year look respectable in this context, with some of the largest increases seen in services like education and recreation. Forecasting inflation is difficult given uncertainty over commodity prices and the yen. Should crude oil consolidate around recent levels or rise further, this would translate into higher input costs in many different categories. Recent yen strength could have the opposite impact by lowering import prices, and lower import prices are already appearing in daily inflation statistics compiled by the University of Tokyo. The rise in the yen[1]For example, the yen rose 7% against the US dollar in February despite the BOJ’s rate cut; over the last 12 months it is up 6%. probably helps explain the BOJ’s surprise decision in January to move its base rate to negative territory, though elevated uncertainty about the economic outlook for regional neighbors like China also played a role.

Limited gains in growth and inflation generate significant media attention, but Abenomics has been more successful in encouraging structural reforms. Companies have increased their focus on profitability and shareholder returns. Despite the recent pullback, the return on equity of 8.3% for the MSCI Japan is nearly double what it was a little over three years ago. A variety of forces stand behind this resurgence, including the aforementioned tax cuts as well as soaring levels of share buybacks. Buybacks in fiscal year 2015 rose to a record ¥5.9 trillion according to Goldman Sachs; 2016 is off to an even more impressive start with the ¥2.2 trillion announced thus far—a more than 200% increase over last year’s level. Companies are also opening up corporate boards to outside directors and reducing the cross-company shareholding that could make managers resistant to change. According to Nomura, last year cross-company shareholding levels hit their lowest ever levels and are expected to decline further in 2016.

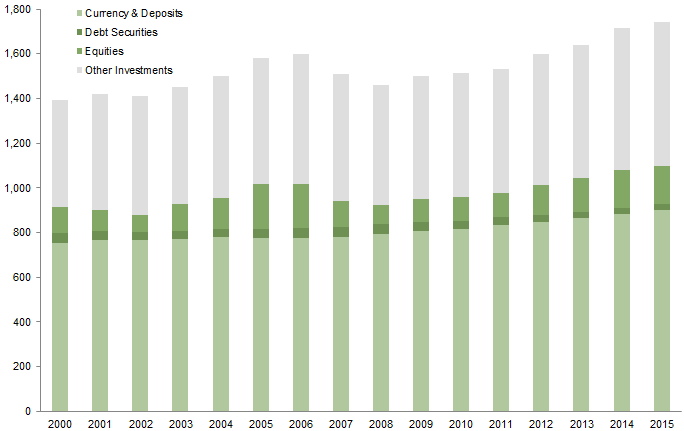

A more legitimate concern about Abenomics is that, at least thus far, it has failed to encourage companies to evenly distribute the benefits from lower taxes and various structural reforms. Workers are frustrated by their failure to share in growing corporate profits via higher wages. Meanwhile, savers and especially retirees have been hit by interest rate cuts. Japanese households are among the world’s largest savers and sit on over ¥1,700 trillion in assets; roughly 50% of this sits in bank accounts and generates very little income (Figure 2). Going forward, it seems likely that the government will respond to anemic demand and its fading popularity. Many expect further fiscal stimulus in 2016 and perhaps a postponement of the scheduled April 2017 increase in the consumption tax.

Source: Bank of Japan.

Equities Remain Attractive

For more on negative interest rates please see Wade O’Brien et al., “Feeling Negative About Sub-Zero Interest Rates,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, March 25, 2016. For our comments on investor concerns, see Wade O’Brien et al., “Japanese Equities: It’s Not Too Late to Capitalize on the Recovery,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, January 2016.

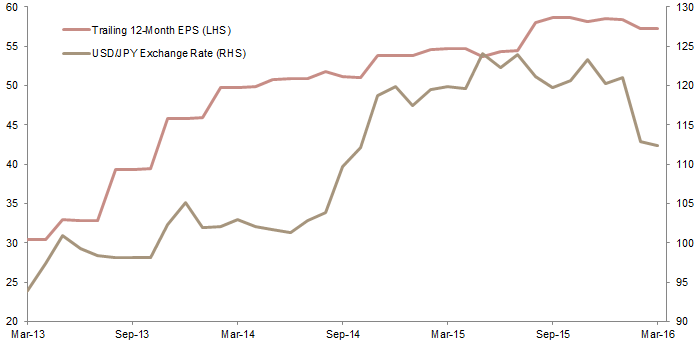

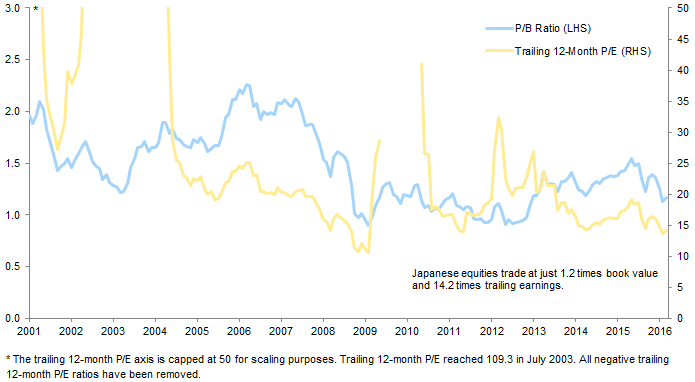

At first blush, lackluster domestic economic growth, uncertainty over key trading partners like China, and negative interest rates do not create a favorable macroeconomic backdrop for equity investors. Still, as we have stated in the past, these concerns should not distract investors from the more promising micro. Improvements in corporate governance and a renewed focus on profitability have resulted in a surge in Japanese corporate profitability. Profits for the MSCI Japan have risen around 90% over the past three years (Figure 3) and, the slow domestic economy notwithstanding, are expected to have grown around 6% in the fiscal year that ended March 31. Equity valuations have cheapened and offer a margin of safety if earnings disappoint. Japanese equities trade at just 1.2 times book value, and 14.2 times trailing earnings (Figure 4); both are in the bottom quartile of recent observations and represent a discount to global peers.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Note: Japan’s fiscal year is from April to March, and is represented by the period in which it begins; for example, the fiscal year from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2016, is called fiscal year 2015.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

The recent appreciation of the yen does pose a risk to earnings, especially for export-oriented sectors and those (like auto manufacturers) that generate the majority of their revenue overseas. The recent Tankan survey, which showed that companies may actually cut capital expenditure by around 5% over the next 12 months, reflects these concerns. The more constructive news is that managers are well aware of the difficulties in growing revenue in a slowing economy and thus have become active acquirers of foreign assets. Japanese companies made over ¥10 trillion of overseas acquisitions in 2015, an all-time record.

Expectations of weaker earnings growth have weighed on shares in recent months; the consensus now expects earnings will grow 10% in the current fiscal year (which ends March 31, 2017), roughly half what it expected just six months ago. Still, even this lower revised rate compares favorably with that of other global large-cap indexes. Eurozone earnings may only grow 6% in 2016 and US earnings growth may be just a quarter that rate. Currency appreciation has been blamed for many of the downgrades, but has a silver lining. Japan imports most of its oil and natural gas, as well as substantial amounts of medicine and medical devices. To the extent that Japanese consumers spend less money on these items, they will have more to spend on other domestically focused categories like food, clothing, and tourism.

For more on this please see Wade O’Brien et al., “Japanese Equities: It’s Not Too Late to Capitalize on the Recovery,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, January 2016.

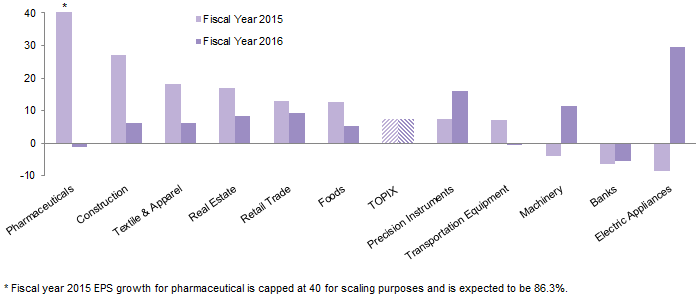

Fund managers (and investors) looking to shield themselves from currency strength have several options. Sectors that derive the majority of their revenue from the domestic economy are expected to see healthier earnings growth; examples include retailers, real estate development and construction firms (which benefit from falling rates and rising demand in key cities), and food and beverage (Figure 5). Pharmaceutical companies (which help treat the aging population) are expected to see profit growth taper off next year, but this follows an expected 86% increase in earnings during the most recent fiscal year. Japanese small- and mid-cap indexes in general are also more reliant on domestic sales and include service firms that operate in growing service categories like employment, child care, and real estate brokerage. Rising Japanese land prices belie the deflation concerns that exist in some circles, with shopping districts popular with tourists faring particularly well. Some small companies have little or no coverage from sell-side analysts, further boosting the alpha-generation potential for managers.

Figure 5. Topix Fiscal Year 2015 and Fiscal Year 2016 EPS Growth Forecasts

As of March 4, 2016 • Year-Over-Year Growth (%)

Sources: Daiwa SB Investments Ltd., Toyo Keizai Inc., and Tokyo Stock Exchange Inc.

Note: Japan’s fiscal year is from April to March, and is represented by the period in which it begins; for example, the fiscal year from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2016, is called fiscal year 2015.

Financial sector profits may be adversely impacted by the BOJ’s new negative rates policy, and securities firms and insurance companies have seen steep earnings downgrades over the past several months. Insurance companies are especially vulnerable as lower long-term rates increase the value of liabilities such as annuities; for securities firms, trading and marketing bonds with near-zero yields is no easy task. The outlook for banks may be more nuanced. Banks would suffer from an inability to pass negative rates on to savers (the concern is that depositors would rather withdraw deposits than be charged to hold money in a bank), but only a very small percentage of bank reserves with the BOJ (amounting to just 2% of GDP) are subject to negative rates. Were rates to go more negative, Japanese banks could try to make up for this by charging higher fees such as those levied on ATM withdrawals, checking accounts, etc.

Technicals have been poor for Japanese equities since the middle of 2015 and could continue to weigh on performance in the near term. Foreign investors have sold nearly ¥5.7 trillion of equities since last July, with most of the selling coming from European and, to a lesser extent, Asian accounts. This gels with speculation that much of the recent selling pressure has come from offshore investors like sovereign wealth funds. Rising share buybacks have offset some of this selling pressure, defying the old adage that companies unwisely buy their own shares at the top. Further support could come from several directions, including more exchange-traded fund buying from the BOJ and also pension funds closing some of their underweights to domestic equities. In any event, foreign selling pressure should eventually fade as positions are trimmed, and the recent stabilization of oil prices could alleviate pressure on certain sovereign wealth funds.

Conclusion

Recent economic data in Japan have been lackluster but are not the huge disappointment certain dramatic headlines suggest.[2]See, for example, Mehreen Khan, “Can Anything Rescue Japan From the Abyss?,” The Telegraph (United Kingdom), March 28, 2016, or Eleanor Warnock and Takashi Nakamichi, “Market Meltdown Threatens … Continue reading Growth looks in line with long-term averages, and statistics such as employment, land prices, and merger & acquisition activity suggest some of the most pessimistic narratives have been oversold. Inflation is higher than when Abe came into office, and could rise further if commodity prices stabilize at current levels or even recover. Investors should not lose focus on the micro—Abenomics has successfully boosted profits and has encouraged greater distributions to shareholders. The unwillingness of companies to share these spoils with workers has dented Abe’s popularity, though the government may take further steps to improve the plight of households such as boosting spending or deferring planned tax increases. Current valuations for Japanese stocks provide a cushion if companies see further earnings downgrades. Further yen strength poses a risk, as does the introduction of negative rates for financials. Both of these forces have silver linings, including the reduced cost of imports and the lower borrowing costs for leveraged companies. We retain our tactical overweight to Japanese equities versus US equities, which feature stretched valuations and limited prospects for earnings growth. On balance, offshore investors should continue to hedge some of their exposure to the yen given the low cost of such hedges and the likelihood the government tries again to push down its value. This said, we recognize that some of the forces that put pressure on the yen are reversing or at least stabilizing (including interest rate differentials and a growing current account surplus), and unhedged positions may benefit if further market volatility is accompanied by Japanese investors repatriating offshore funds.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Nroop Bhavsar, Senior Investment Associate

Footnotes