Demand for collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) has soared in recent years, despite lingering suspicions about asset-backed securities due to their role in the global financial crisis (GFC). Investors have recognized the attractive qualities of the asset class, such as relatively high yields, low default rates, and floating-rate coupons, which reduce sensitivity to rising interest rates. Investors can choose from a variety of pooled vehicles through which to access CLO debt and equity, including those that offer exposure to specific slices of the capital stack, multi-asset mandates, and those that offer exposure to assets (debt and/or equity) from either externally or internally managed transactions.[1] Some funds offer exposure to purely “third-party” debt and equity from externally managed CLOs, while others provide a blend of exposure to external deals and CLOs managed by other arms of the … Continue reading Careful manager selection is essential in the current environment, given the weakening protections provided by loan documentation, as well as technical pressures that can quickly shift the relative value opportunity. This paper provides an update on recent trends in the CLO market and discusses what we believe are some of the more attractive implementation options.

Growth of the CLO Market and Recent Returns

The CLO market has grown strongly in recent years, as soaring issuance of leveraged loans has created a rich opportunity set for CLO managers. CLO launches hit $117 billion last year in the United States, a near record, and 2018 is on track to exceed this amount (Figure 1). This issuance brings the total CLOs outstanding in the United States to more than $550 billion, with roughly another €75 billion outstanding in Europe. The size of the CLO market now exceeds that of the US non-Agency CMBS market, and is approaching that of the non-Agency RMBS market. These issuance numbers do not include significant amounts of repriced deals,[2]Over $80 billion of CLO deals have been repriced in 2018 alone, according to Wells Fargo. which also expand the opportunity set for investors.

Sources: Thomson Reuters and Wells Fargo Securities.

Note: Data for 2018 are through September 30.

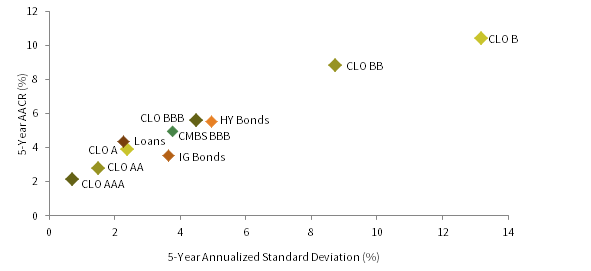

Surging loan issuance is not sufficient to explain the popularity of this asset class; strong absolute and relative performance has attracted investors. CLO debt has outperformed similarly rated corporate debt in recent years (Figure 2), with BB-rated CLO debt handily outpacing US high-yield bonds despite weaker credit ratings for the latter. Volatility has been higher than comparable asset classes, though much of this in recent years stemmed from the commodity-driven sell-off in late 2015 and “risk retention” concerns, which seem unlikely to repeat in the near future.[3]The risk retention rule requiring US CLO managers to retain 5% of the economic interest in new deals was rolled back in early 2018. From a fundamental perspective, CLO debt has recently suffered near-zero defaults or impairments.

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Credit Suisse, and J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc.

Notes: Annualized based on monthly data. Asset class returns and standard deviations are represented by: J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO AAA Index (CLO AAA); J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO AA Index (CLO AA); J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO A Index (CLO A); J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO BBB Index (CLO BBB); J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO BB Index (CLO BB); J.P. Morgan CLOIE CLO B Index (CLO B); Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index (Loans); Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High Yield Index (HY Bonds); Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Index (IG Bonds); and Bloomberg Barclays US CMBS Baa Index (CMBS BBB).

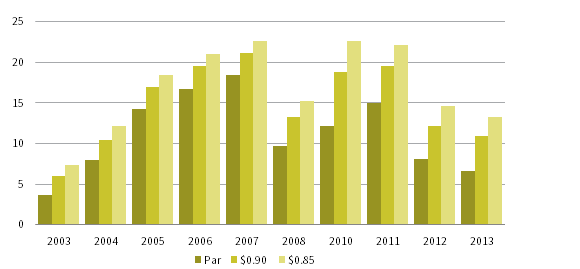

CLO equity has also generated impressive internal rates of return (IRRs), but several dynamics make about it harder to generalize about performance. One is that CLO equity is sold over the counter and newly issued equity is often sold at different prices to different investors. For example, a specialist CLO equity investor that works with an investment bank to structure a deal and commits to buying a majority of the equity may get a better price than another asset manager buying a smaller stake. Another is that calculating the value of the equity tranche depends on many assumptions, including when the liabilities will be repaid. Wells Fargo calculates a range of IRRs for recent CLO equity in terminated (fully wound-down) CLOs based on a range of potential purchase prices (Figure 3). While modeled CLO equity IRRs assuming an initial price discount are impressive, it is worth noting that the difference between top and bottom quartile returns (not shown) can be significant—pointing to additional upside for skilled investors that can access these discounts, choose superior CLO collateral managers, and successfully trade the portfolios.

FIGURE 3 TERMINATED BSL CLO EQUITY IRR PERFORMANCE BY PURCHASE PRICE

As of Second Quarter 2018 • Percent (%)

Source: Wells Fargo Securities.

Note: “BSL” refers to Broadly Syndicated Loan.

How CLOs Work

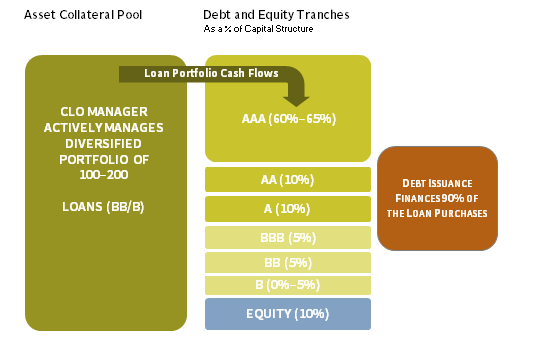

A CLO is a bankruptcy-remote special purpose vehicle (SPV) created to invest in a pool of leveraged loans. The SPV is established by a collateral manager who supervises the loan pool going forward (overseen by a trustee). With the assistance of an underwriter, the CLO raises funds to purchase the loans by issuing debt securities secured by a claim on the loans, as well as by selling (or internally funding) a residual equity exposure. A typical capital structure for a new CLO is illustrated below.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

CLOs employ several structuring techniques to obtain the highest possible credit ratings for these various tranches of debt. A securitization concept known as “waterfalls” ensures that interest received on loan assets is first used to make coupon payments for AAA-rated notes, then AA-rated notes, and so forth. Overcollateralization (OC) tests are used over the life of the CLO to ensure the pool’s collateral is sufficient to cover the claims of different types of debtholders, with more senior liabilities requiring greater amounts of excess collateralization.

CLO debt investors also benefit from other restrictions on what CLO managers can do regarding the credit quality of the pool. A minimum weighted average rating factor (WARF) test ensures that average credit quality stays above a certain level. In addition, the pool’s maximum exposure to individual credits, credit received for CCC-rated loans, sector concentration, and many other aspects of the structure are restricted.

CLOs are designed to be self-correcting. If during the CLO’s life it breaches any of these requirements, the CLO manager must take steps to rectify the situation, such as using interest received from assets to pay down debt or buy higher quality collateral. Though they share many similar characteristics, no two CLOs are structured exactly the same way. This variation across structures ensures a relatively fertile opportunity set for CLO debt and equity investors.

Stages of a CLO’s Life

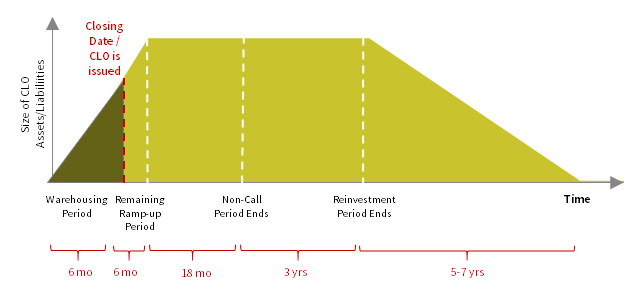

CLOs typically have legal maturities up to 12 years, though structures can vary and the actual life will depend on factors such as the pricing and performance of the underlying loan market. Figure 4 illustrates the main stages of a typical CLO’s life. During the first stage, the CLO manager uses an account (“warehouse facility”) with a third-party (usually an investment bank) to begin acquiring a pool of leveraged loans. A secured financing line typically provides around 75%–80% of the purchase price of the loans, and other investors (or the CLO manager itself) provide the remainder and bear the first-loss risk. Once the pool has grown to the desired size and characteristics, the CLO is formally launched, and following a short ramp-up period of between one and six months, the underwriter sells debt and equity from the CLO to investors, using the proceeds to repay the warehouse financing.

Source: Goldman, Sachs & Co.

During the reinvestment period, and subject to various restrictions governing average credit quality in the pool, average dollar price, and other criteria, the CLO manager may trade the collateral pool by buying and selling loans,[4]This is true of dynamic CLOs, but is not the case for so-called “static” CLOs, where the assets do not change after ramping up. as well as reinvesting proceeds from maturing loans into new investments. This reinvestment period has stretched in recent transactions to as long as five years. The reinvestment period is followed by a harvest period, where proceeds from maturing loans can only be used to repay senior notes and eventually equity holders. As with the interest payment waterfalls, principal repayment on liabilities is made according to seniority. Equity holders collect whatever excess interest remains from loans after payments on liabilities have been made, and only once other debt is paid down does the equity tranche begin collecting proceeds from maturing loans. Typically, the excess spread received by equity investors is substantial during the early life of the CLO and helps reduce their exposure, boosting rates of return. However, to the extent that hiccups arise shortly after launch and this excess interest is reduced (for example, because assets default and interest is diverted), returns can be much lower.

Typical CLO documents give the collateral manager[5]The owner of a majority equity stake in a CLO can replace a CLO manager that does not manage the transaction in its best interests, so these rights could also be considered as belonging to the equity. call rights (the option of collapsing the deal after a certain minimum amount of time). When the manager exercises call rights, the CLO liquidates its loan assets and uses the proceeds to repay debt and equity holders. The non-call period usually lasts around two years, though in some recent deals the period has been shorter. The CLO manager often chooses to call the CLO after the reinvestment period ends and the deal deleverages, lowering returns to the equity holder. Although less common, a CLO manager might be motivated to call the deal if the income generated by the assets is not sufficient to cover required interest payments and generate a reasonable return for its equity, and no change to this situation is envisaged. This second situation is less common because most CLOs allow the manager to refinance the liabilities after the non-call period has ended; repricing the CLO debt at lower spreads will improve the economics for equity holders.

Evaluating CLOs

The attractiveness of CLO debt or equity is driven by several things (other than price) including the capability of the CLO manager, the structure of the CLO (for example, the specific protections it affords), and (for CLO equity) its cost of funding. The skill of the CLO manager is paramount, as over the life of the CLO, the composition of loans may change entirely and thus the initial pool may not accurately reflect the real risk to investors.[6]Unless the CLO is “static,” meaning the collateral does not rotate over its life. Skilled CLO managers that can identify improving credits and thus underpriced loans have the opportunity of rotating into less expensive assets of similar quality, subject to various credit quality and other tests. These managers may also be more likely to avoid weaker companies that experience operational problems and see their debt fall in value (or incur rating downgrades), forcing other CLO managers that might have purchased these assets to add more collateral.

CLO-specific requirements, including average credit ratings, may mask tail risks that are greater in some CLOs than others. The likelihood that a CLO will be called can also materially impact the price of CLO debt and equity. For example, investors that correctly anticipate that it will be economical for a CLO manager to call a deal may profit if they are able to obtain debt in the CLO at several points below par in the secondary market. Conversely, buying equity in a CLO that struggles to deleverage (due to weak asset performance) can result in sub-par returns.

Assessing the quality of the structure also comes into play. In certain vintages, for example, the equity tranches of CLOs with larger OC cushions have outperformed peers, presumably because the CLO manager had more leeway when conditions weakened to take advantage of cheaper prices by mopping up underpriced assets.

CLO Investors and Investment Vehicles

A variety of investors are attracted to the diversity of implementation options offered by CLOs. Highly rated CLO debt is often purchased directly in the new issue or secondary market by investors with defined liabilities such as pensions, insurance companies, and banks. At the other end of the spectrum, CLO equity is often purchased by specialized investors including business development companies, private equity firms, and hedge funds. Lower-rated CLO debt falls somewhere in the middle, attracting many types of investors, such as asset managers and insurance companies.

Potential limited partners looking for pooled exposure (exposure to debt and/or equity from a diversified pool of underlying CLOs) have a variety of investment options, including hedge funds, commingled open-ended vehicles, and lock-up funds. Mandates vary across these funds. Some focus exclusively on securities from CLOs managed by other parties (a pure third-party strategy), while other funds may allow the manager to combine debt or equity from CLOs managed in-house with those of outside managers. Some funds focus on debt or equity while others offer a blend of exposures. Drilling further, there are numerous sub-strategies, including vehicles that focus exclusively on low-duration, highly rated CLO paper, as well as those that focus on mezzanine (BB- and B-rated) debt.

CLO investors must navigate conflicts of interest, especially in instances where a commingled fund is buying debt or equity from CLOs managed by other teams housed within the same asset manager. CLO debt and equity investors can have competing interests, as the former have a capped upside but hope for a given amount of interest payments, and the latter may want to boost risk or simply call a deal if returns are expected to be sub-par, eliminating coupons for bondholders. Equity purchased from an internal team’s CLO must be purchased at a reasonable price, preferably accompanied by concessions (such as a share of the management fee going forward) that would be negotiated with an external seller. The owner of a controlling equity stake in a CLO should replace the manager if it is not managing the portfolio in the best interests of the equity tranche. Firing a CLO management team housed within another silo of the same fund management group may be a difficult decision.

Attractive Options in the Current Environment

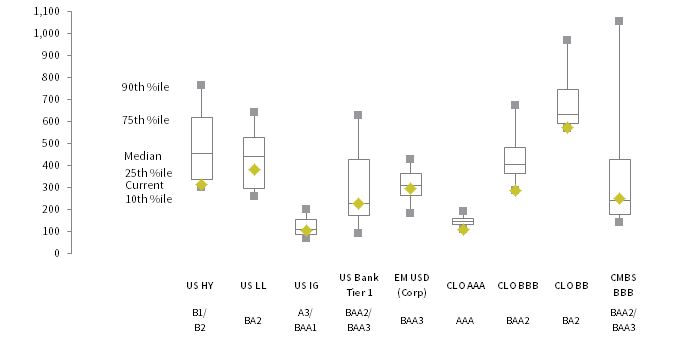

The floating-rate nature of CLO debt has helped insulate the asset class from rising rates in 2018, and this may continue into 2019. While below levels earlier in the cycle, current CLO spreads look attractive across the curve, so ideal exposure for investors will depend on their tolerance for credit risk, volatility, and liquidity. Looking at Figure 5, current discount margins on BB-rated CLO paper of around 575 basis points (bps) are well above those on high-yield bonds (316 bps spread), despite a much lower credit rating for the latter (B1/B2). CLOs currently offer elevated spreads, despite historical default rates that are much lower than similarly rated corporate bonds. One study noted that the long-term cumulative default rate for BB-rated CLO debt was 1.7%—roughly one-tenth the comparable default rate for similarly rated corporate bonds.[7]Standard & Poor’s Rating Services, “Twenty Years Strong, A Look Back at US CLO Ratings Performance From 1994 Through 2013,” January 2014. Both structural complexity and the less liquid nature of CLO debt might help explain this spread premium.

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Credit Suisse, and J.P. Morgan Securities.

Notes: Asset classes represented by: Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High Yield Index (US HY), Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index (US LL), Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Index (US IG), Bloomberg Barclays Capital Securities Tier 1 Index (US Bank Tier 1), J.P. Morgan CEMBI Diversified Index (EM USD [Corp]), J.P. Morgan CLOIE AAA Index (CLO AAA), J.P. Morgan CLOIE BBB Index (CLO BBB), J.P. Morgan CLOIE BB Index (CLO BB), and Bloomberg Barclays US CMBS Baa Index (CMBS BBB). Observation periods begin: January 31, 1994 for US HY; January 31, 1992 for US LL; June 30, 1989 for US IG; December 31, 2001 for US Bank Tier 1 & EM USD (Corp); December 31, 2011 for CLO AAA, CLO BBB, and CLO BB; and August 31, 2000 for CMBS BBB.

CLO debt is not without its risks, and caution prevails in some quarters. Some analysts worry that surging CLO new issue volumes will push spreads even wider later in 2018, while others worry that slower repayment rates on CLOs will mean creditors are repaid more slowly, reducing potential demand from reinvested cashflows. The weak underwriting quality of new leveraged loans is a more general concern, though we would note that CLOs are far from the only asset class exposed to this issue.

CLO equity is harder to generalize about and implement from a tactical perspective, with many moving pieces that make timing more difficult. Current underwriting standards on loans, CLO liability pricing, and other market technicals, which influence how quickly a CLO sees its loan assets repaid and thus deleverages, all come into play. The rising share of B-rated loan issuance (around 63% of year-to-date supply) and the growing presence of these lower-quality loans in CLOs is sparking concern over downgrade risks (if CLOs exceed their CCC thresholds, they may need to buy more high-quality assets, impairing cash flows for equity investors). Third-party CLO equity funds (and mixed asset funds) can help navigate these challenges by influencing deal structures and collateral quality when the CLO is formed. In addition, CLO equity funds can help improve their economics by receiving a rebate on fees from the CLO manager in exchange for their role in helping the deal’s formation.

Timing aside, adding CLO equity to portfolios can provide benefits that include diversification, current income, and capital appreciation. CLO equity can also help mitigate the so-called “j-curve” effect in private portfolios because initial cash flows are typically significant. To get a sense of this, one can look at the current arbitrage rate on new CLOs (difference between asset income and debt payments) and see how much cash equity holders have received in recent deals. According to Wells Fargo, 2015 and 2016 vintage CLOs have returned the equivalent of 45% and 20% of the par value of equity from those vintages, respectively, though any equity investor buying at a discount will have received an even higher percentage of their investment.

Loan documents are declining in quality, but the offset for CLO equity investors now is that they are locking in inexpensive liability spreads that could remain in place for up to a decade. If the credit cycle turns in the next three to four years (i.e., before the reinvestment period of new CLOs terminates), managers will be able to reinvest the proceeds from maturing loans into cheaper assets, boosting returns for CLO equity. This helps explain why, as shown above, IRRs for 2006 and 2007 vintage CLO equity were so high.

For investors that are concerned about trying to time the CLO opportunity, given the potential for volatility as 2018 comes to a close, a third-party multi-asset fund may be a good option. These fund managers will try to navigate the potential technical pressures mentioned earlier. Some of these funds may also include an allocation to warehouse financing (funding the residual position that arranging investment banks do not wish to fund when a CLO is ramping up). The scale of this business can fluctuate, but IRRs tend to be high, though they are limited to short time horizons.

Conclusion

Investors have few compelling options in liquid credit today, with spreads on high-yield bonds trending toward post-crisis lows and underwriting standards in the leveraged loan market steadily slipping. CLO debt is more attractive than either of these assets, especially when accessed via a third-party manager that is likely to avoid debt from lower-quality transactions and is well-placed to make relative value decisions for investors given familiarity with underlying loan portfolios. CLO equity is a different asset class, but also attractive. Historical returns have been high, especially from well-managed deals. CLO equity also offers significant cash flows early in the deal’s life, and the current pricing of CLO liabilities mean these equity holders will be well-placed to reap the benefit of any future turndown in the credit market that would allow them to reinvest in cheaper loans. Investors interested in CLO equity have a variety of implementation options, but as with CLO debt, we recommend experienced managers that have the systems, teams and sourcing to harvest the best economics for investors.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Brandon Smith, Senior Investment Associate

Footnotes