The recovery rate on senior loans looks poised to fall in the next cyclical downturn, as weaker structures and terms impact the market

- The increased use of unitranche loan structures, which by definition do not have junior debt, have reduced senior debt’s cushion to absorb losses

- Senior loan recovery rates are likely to be also impacted by inflated cash flow assumptions and lax terms governing the borrower

- Investors considering an allocation to a senior debt fund should keep an eye on these trends and understand how its manager intends on navigating these challenges

Our concerns over the leveraged loan markets have grown recently. Specifically, we see deterioration in both terms and conditions, as well as in cash flow assumptions in the sponsor coverage, senior debt (direct lending) market. These phenomena are mainly present in the unitranche, or loan-only, corporate capital structures that finance leveraged buyouts (LBOs), dividends, and recapitalizations. In this research note, we highlight our concerns and consider how the cocktail of unitranche loans, inflated cash flow assumptions, and weak terms could threaten recoveries in the next cyclical downturn.

Since past experience informs expectations, historic recovery rates are a sound place to start when considering future recovery rates. To be sure, recoveries on senior loans vary by the information provider. Standard & Poor’s estimates that recovery rates on senior bank debt have ranged between 60% and 89% depending on the amount of capital subordinated to it. In contrast, New York University, which is another leading data source for this market, pegs the average annual weighted recovery rate of senior debt from 1983 to 2016 at 59.1%.

However, these calculations are based on borrowers with capital structures that typically had junior debt, which is less common today. Historically, a senior lender may have lent the equivalent of 3.0x EBITDA to the borrower, with bondholders lending an additional 2.0x EBITDA, raising total leverage to 5.0x EBITDA. As a result, for the senior lender to become impaired, the enterprise value of the borrower would need to decline to the point where equity investors and bond holders lost all their value. But if the traditional senior lender lent the full five “turns” of EBITDA, meaning it had a unitranche structure, only the equity piece would serve as a cushion.

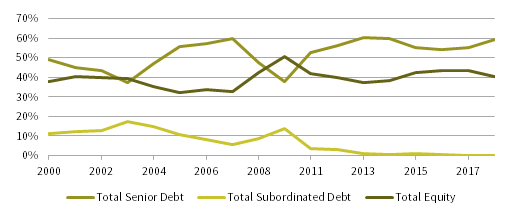

The trend toward a unitranche structure is particularly visible in the financings of LBO transactions (Figure 1). Historically, subordinated debt provided a level of cushion to holders of senior debt, but that cushion has virtually disappeared in more recent transactions. While private equity sponsors do provide a cushion, senior lenders are closer to the first loss piece without junior debt. As a result, the unitranche structure exposes senior lenders to risks typically held by junior debt lenders.

Source: Standard’s & Poor’s.

Note: Data for 2018 are through June 30.

If unitranche lenders are more exposed to junior debt risk, what level of recoveries can reasonably be expected? The portion of current loan-only structures that map to traditional first-lien debt level may average a 60% to 80% recovery rate, with the junior portion recovering between 20% and 50% on average. Using simple algebra and assuming the unitranche structure consists of two-thirds traditional first-lien debt and one-third traditional subordinated debt, the debt holder could expect a recovery rate near 46% to 70%.[1]Recoveries can range from 0% to 100% of par, plus accrued interest regardless of structure. For purposes of this analysis, we refer to empirically observable, probabilistic, and historical outcomes.

One mitigating factor to this is that loan-only structures give senior lenders virtually complete control over workouts. More complicated structures introduce layers of lenders with their own interests, potentially leading to protracted negotiations. The unitranche removes those complications and allows the lender greater flexibility. That is if the loan documents grant the lender adequate protection!

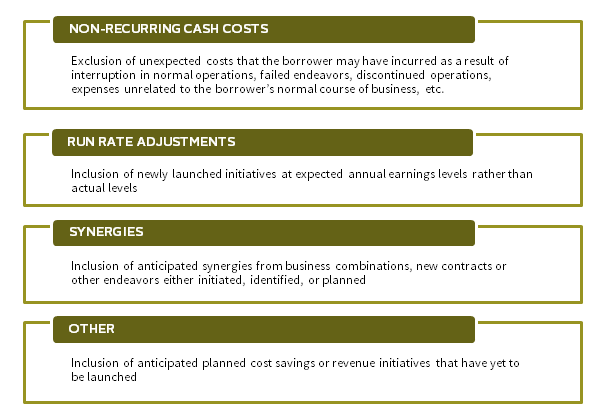

With unitranche loans representing a greater portion of enterprise value, senior debt fund investors should be concerned with inflated cash flow assumptions and weak terms. The former, which tend to take the form of adjustments to EBITDA, impact the financing costs of LBOs. Some of these adjustments are justified, such as easily achievable cost savings, but other adjustments require optimistic assumptions and may be unlikely to materialize. These inflated assumptions mask the enterprise’s true cash flow potential and make it more difficult for lenders (and investors) to gauge the risk of a unitranche loan (Figure 2).

If a unitranche is “too deep” into a capital structure, then lenders can rely on covenants and other protections that allow them to intercede in a timely manner and preserve value. Sadly, many loans are currently covenant-light, meaning that they either have only an incurrence covenant or lack certain covenants altogether.[2]An incurrence covenant prohibits additional borrowers rather than a suite of covenants that polices financial performance. What is infrequently recognized but is almost as important are “covenant-wide” loans, which permit finances to deteriorate so dramatically as to eviscerate creditors’ protections. In other words, covenant-light and covenant-wide loans make it difficult for lenders to intervene in a timely manner to preserve value.

But much like an iceberg, greater peril may lurk below the surface of these trends. Loan terms include not just covenants but also provisions that give borrowers certain liberties free from lender interference. We are concerned about one those liberties—the right to alienate assets. Specifically, par lenders and distressed managers are eyeing how distressed borrower corporate officers can remove assets from a lender’s collateral pool in an effort to generate needed liquidity.

One situation may look something like this: Borrower A’s earnings and cash flow are far worse than its reporting package may suggest, liquidity needs are growing, and a refinancing is looming. Lenders have weak covenants and cannot intervene to protect their principal. Borrower A’s CFO needs cash but is reluctant to turn to his lenders as they might use the opportunity to renegotiate more creditor-friendly terms. If the CFO can transfer collateral to another subsidiary not named in the credit agreement, then he may be able to borrow against them.[3]Credit opportunities funds often engage in such transactions. This transfer may adversely affect recoveries.

Limited partners should consider these trends when allocating to senior debt (direct lending) funds, as these realities may conspire to drive recovery rates to new lows. In underwriting these funds, we think investors should carefully review examine internal documentation to understand how a manager will address these challenges. Will investment memoranda clearly identify EBITDA adjustments and scrutinize their achievability? Will loan documentation properly restrict transfers of borrower assets? Will leverage levels be appropriate? Ensuring you’re invested in a thoughtful manager will be essential to maintaining performance through the next cycle.

Tod Trabocco, Managing Director

Footnotes