The renminbi (RMB)[1]The Chinese currency, known as the renminbi or yuan, has two different exchange rates. CNY is the rate for onshore RMB, while CNH is the offshore, Hong Kong–traded RMB. The PBOC sets a daily … Continue reading fell 1.5% over the first four trading days of 2016—a move that coincided with a renewed slump in Chinese equities and tumbling oil prices—helping to trigger panic in global markets. January’s decline was less sharp than the 3% decline over August 11–13 that also sent markets into a tailspin, as the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has intervened and held the currency steady since January 8. While the currency has stabilized recently, investors remain on edge about the potential for a large devaluation in the RMB or a full-blown currency crisis in China. Our base case remains that China can avoid a currency crisis, although much depends on investor psychology and how the PBOC manages the capital account. In this research brief, we review recent developments in the RMB and the tough choices facing the PBOC.

Communication Breakdown

The angst over what are relatively small moves in the RMB stems partly from the PBOC’s lack of transparency and clear communication about its currency policy and objectives. This has caused confusion both domestically and internationally.

The PBOC explained the surprise “mini-devaluation” in August as a shift toward a more market-driven exchange rate made by basing the daily fixing rate on a moving average of quoted exchange rates. The fixing was higher than the market, which led to the downward adjustment. This change was presumably to address issues raised by the International Monetary Fund about potentially including the RMB in the special drawing rights (SDR) basket. However, the timing could not have been worse, occurring on the heels of a collapse in China’s domestic stock markets and amid widespread weakness in emerging markets currencies ahead of a potential US Federal Reserve rate hike. The lack of forewarning from the PBOC likely also contributed to market volatility.

Comparing China’s Trade-Weighted Basket for the RMB to the USD/CNY Exchange Rate

December 31, 2013 – January 31, 2016 • Rebased to 100 at December 31, 2013

What’s in China’s Trade Basket?

The table below shows the composition of the China Foreign Exchange Trading System (CFETS) basket. Unlike the more widely used Bank for International Settlements family of baskets, the CFETS appears to be more biased toward the major developed markets currencies, with the US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, and Hong Kong dollar (effectively the US dollar given its peg) accounting for 70% of the index. Interestingly, no Latin American currencies are included, which is ironic given how hard the Brazilian real has fallen partly due to China worries.

Source: China Foreign Exchange Trading System.

Further complicating matters, the PBOC introduced a new trade-weighted basket for the RMB in December, and while the bank has made references to the performance of this basket, it has not explicitly stated that it is targeting this basket. Despite the decline in the CNY exchange rate versus the US dollar, the new RMB basket has essentially been flat since the end of 2014. Furthermore, the devaluation in August and renewed weakness since late October coincided with RMB strength in basket terms.

Some analysts argue that if the PBOC is targeting a stable basket, then recent RMB weakness has achieved this by reversing the previous run-up. Thus, any additional RMB weakness will simply be a reflection of broad USD strength (and vice versa). However, this view assumes that the PBOC is targeting stability relative to the end of 2014. Going back one year to 2013 implies that a larger move downward in the basket is needed to reverse the broad strength in the RMB since the middle of 2014, when the RMB index diverged from the USD exchange rate.

Market uncertainty stems from the lack of clarity around whether the PBOC wants a stable basket at today’s level or prefers to push the RMB lower in broad terms. Either way, the PBOC seems to have misjudged how markets and domestic players would react to modest RMB weakness. With the consensus both inside and outside of China that the RMB is set to weaken, demand for US dollars from both mainland companies and individuals has surged, testing China’s increasingly porous capital controls. For now, the central bank has gone into bunker mode and is again prioritizing stability in the USD exchange rate, while press reports indicate attempts to tighten up existing capital controls.

The Trilemma: What Will the PBOC Choose?

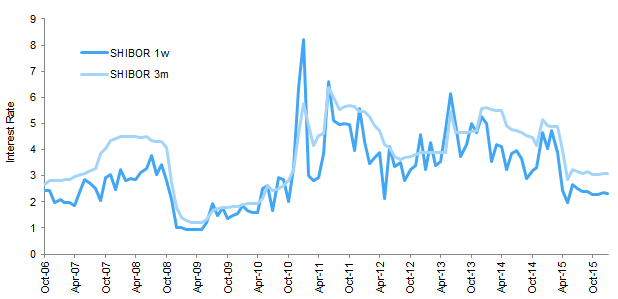

The PBOC is stuck in a difficult situation; it cannot control both the currency and interest rates and have even a semi-open capital account (the so-called currency trilemma). Short-term rates in China have been steady recently and at relatively high levels compared to 2008/2009, despite an arguably weaker economy. Given China’s debt burden, the PBOC should prioritize having control over interest rates.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Yet, the PBOC is also concerned that if it pushes interest rates down or lowers the required reserve ratios for banks, this excess liquidity will simply flee China, putting more pressure on the currency. The direction of the USD/CNY exchange rate is sensitive to the yield spread between Chinese and US bonds, as lower interest rates in China and/or higher rates in the United States encourage more outflows. Thus, before the PBOC can further ease monetary policy, it must stem the tide of capital outflows that have accelerated over the past year. This implies the PBOC should further tighten capital controls, which it seems to be doing on the margin.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Some commentators have argued that the PBOC might be forced into a “pre-emptive strike” to depreciate the RMB to a level that makes it attractive to investors, rather than a slow decline over time that keeps the possibility of a larger move on investors’ minds. While possible, a quick depreciation runs the risk of creating even more market uncertainty and loss of confidence. Such a move also runs counter to the risk-averse nature of Chinese policymakers, who are likely to prioritize stability above anything else. Yet it cannot be ruled out, especially if defending the currency starts to put upward pressure on interest rates. Furthermore, the PBOC is known to surprise markets; current rumors hint that such a move could occur during the week-long Chinese New Year holiday, when China’s banks and financial markets are closed. With the Bank of Japan instituting negative interest rates at the end of January and the European Central Bank stating it may expand its QE program in March, the PBOC may feel it needs to quickly join the “currency war.”

In the meantime, the PBOC could help calm nerves by clarifying what role, if any, the currency basket actually plays in monetary policy. Singapore, for example, targets a currency basket and provides broad guidance on the direction of the basket and trading band. The downside to such an approach is that it requires giving up control of domestic interest rates, and a historically closed institution like the PBOC may find such transparency challenging.[2]For further explanation of how the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) manages the Singapore dollar basket, please visit http://www.mas.gov.sg/monetary-policy-and-economics/monetary-policy.aspx. But if the PBOC can convince investors that it is targeting a band around the currency basket and not a broad-based devaluation, then market participants would be willing to step in and buy the RMB as it approaches the lower band, if they have confidence the PBOC will support the basket. At a minimum, making clear the basket is the target will make investors less concerned should the RMB weaken again amid renewed USD strength.

What’s Next?

The market consensus as recently as mid-2015 was that the RMB would remain stable and appreciate modestly over the next few years, in light of increasing investor demand for the currency stemming from the internationalization of the RMB and opening of China’s domestic asset markets (equities and fixed income) to foreign investors.

See Aaron Costello et al., “Escalator Up, Elevator Down? Recent RMB Weakness,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, March 27, 2014.

In March 2014 we made the case instead for continued RMB weakness, citing the need for China to ease monetary policy to help support growth and the fact that the currency was becoming increasing overvalued, especially on a trade-weighted basis. Our view was that a controlled depreciation of the RMB of perhaps 5% to 10% could occur, but a sharp devaluation (15% to 20%) was unlikely. Since the end of 2013, the currency is down 8% versus the US dollar, within our expected range.

We now expect further weakness in the currency given the additional broad strength in the RMB since mid-2014. Ideally the PBOC should guide the RMB basket lower and reverse the previous run-up, which was most likely due to a desire to keep the currency steady versus the US dollar during last year’s SDR negotiations. While SDR inclusion was an important symbolic goal for the PBOC (and provided political cover for pushing ahead with financial liberalization), letting the RMB appreciate was a policy error, as it increased deflationary pressure in the economy at a time when the PBOC was trying to lower real interest rates. By allowing the RMB to gradually weaken, the PBOC can lower interest rates and inject more liquidity into the banking system without burning through its FX reserves, the sharp decline in which has caused concern.

The new market consensus is that the RMB will weaken modestly this year to USD/CNY 6.80, or about 3% from today’s 6.58 level. This is based on the view that the PBOC is targeting the RMB basket at the current level, and the US dollar will see only modest upside this year. Notably, the 6.80 level is roughly where the RMB was pegged during 2008–09, so some analysts may be anchored to this number. Both Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have recently downgraded their forecasts to approximately USD/CNY 7.0 (or -6% from current levels), and expect the RMB to weaken further in 2017, based on a view that the PBOC will shift toward a weak basket policy in the second half of 2016 given weaker economic growth.

It would seem that a 7% to 10% decline in the RMB basket is needed to reverse the run-up since early 2014. Yet it is hard to have conviction in how much further the RMB will weaken, as the direction of the US dollar is of critical importance to where the RMB heads; a relatively weak US dollar, especially versus the euro and Japanese yen (which are 36% of the RMB index), would put less pressure on the RMB to depreciate. Thus, the Fed needs to be very careful about when it hikes rates. Futures markets now price in only one rate hike this year. The Fed going back on hold would help drive the US dollar lower, assuming the US economy avoids a recession (otherwise, the US dollar is likely to surge).

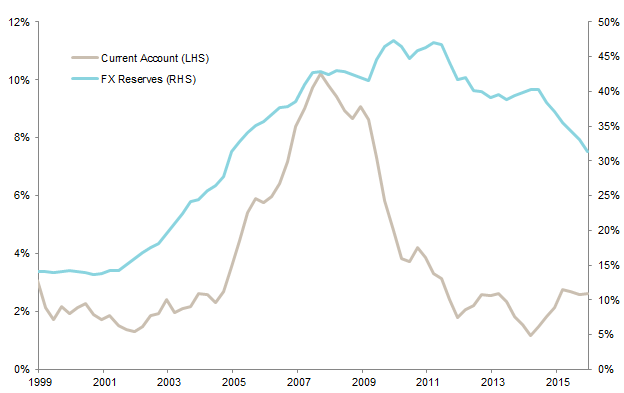

Could China be forced into a large devaluation, such as the 33% devaluation in January 1994 that helped kick-start its export sector? Fundamentally, there isn’t much case for this; China generated a record $600 billion trade surplus last year, which will likely increase this year (in part due to falling commodity prices). A large devaluation would not boost economic growth much, as the economy is driven more by investment than exports. Further, a large devaluation would be counterproductive by causing more stress in the corporate sector, given the increase in unhedged USD borrowing that has occurred over the past few years (with the rush to hedge and/or pay down this debt partly contributing to recent capital outflows).

However, markets are not driven by fundamentals but by perceptions, and the risk is that modest weakness will beget expectations of further weakness, allowing capital account flows to dominate current account (i.e., trade) flows. This could set in motion a dynamic where capital outflows lead to currency weakness, which leads to rising interest rates (as liquidity dries up as FX reserves are drawn down to prop up the currency), which weighs on economic growth, which leads to further capital flight and currency weakness, etc.

As of now, China’s semi-closed capital account, still large current account surplus, and FX reserves provide the tools to avoid a currency crisis, but much depends on investor psychology (both foreign and domestic), which is impossible to predict. Our base case is that the PBOC will attempt to engineer a gradual depreciation of the RMB as it lowers interest rates, rather than seek a one-off devaluation, which could trigger panic. While China’s FX reserves declined by $513 billion in 2015, and a staggering $108 billion in December alone, even at December’s drain rate, the PBOC still has two and a half years’ worth of reserves ($3.3 trillion), not factoring in ongoing current account surpluses. Unlike other emerging markets, China’s problem isn’t that it needs to borrow from abroad to service debts, but that there is too much money trapped inside that wants to leave. We expect additional capital controls and a halting of RMB “internationalization” for now. While China may move ahead with programs designed to attract foreign inflows (such as the recent changes to the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor program), keeping the $8.5 trillion worth of domestic household deposits in the banking system is critical.

As noted in our March 2014 publication, a premature opening of the capital account could trigger a crisis in China, and thus expectations of full capital account convertibility in the near term were, and still are, misguided. By opting to close the capital account, China may be taking a few steps backward, but this could help stabilize the exchange rate and lower interest rates.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

The Bottom Line

Investors should expect more weakness in the RMB as China tries to combat a weakening economy by lowering interest rates and to reverse the damage from holding the RMB steady amid broad US dollar strength. While a currency crisis in China can be avoided, much depends on investor psychology and how China manages the capital account. Some clarity from the PBOC would be helpful in calming markets. However, the outlook for the RMB also depends on the overall strength of the US dollar, making it hard to have conviction in any guesstimate of what level the RMB may reach. Expect uncertainty over the RMB to continue to weigh on global markets and emerging markets currencies this year, even amid a gradual depreciation, while a pre-emptive devaluation cannot be ruled out.

Aaron Costello, Managing Director

Footnotes