Another outbreak of Eurozone distress is not our base case, but more risk-averse investors should understand their options

- Improving economic growth and corporate profits, as well as receding political risk, may make this seem like an inauspicious time to consider another outbreak of political stress in the Eurozone. However, recent events in Spain and next year’s elections in Italy mean some investors are asking whether this is a good time to lock in gains or try to position portfolios for another uptick in market volatility.

- Correctly timing any distress event is difficult and opportunity costs can be significant; building diversified portfolios that include safe haven assets like sovereign bonds would be our first line of defense. However, investors do have other options, including reducing targeted allocations to Eurozone assets, employing derivatives-based strategies, or tactically underweighting related assets.

- For more bearish investors that can avoid tax consequences, reducing equity exposures and buying call options may have some appeal.

The European Union has weathered several potential storms since the decision by voters in the United Kingdom to seek ‘Brexit’ in June 2016. The defeat of anti-EU candidates in various national elections earlier this year, combined with rebounding economic growth and company profits, have boosted confidence and sent local equity markets to new heights. While concerns about a Eurozone breakup seem to have been allayed, recent election results in Germany and the independence referendum in Catalonia have reminded investors of the tensions and potential vulnerabilities underlying the European project. As 2018 will present further tests, some investors are asking whether and how to protect against the possibility of an extreme outcome.

We think there is a low probability of an extreme event like the breakup of the Eurozone, and typically do not advise investors to position portfolios for extreme events. We remain proponents of diversified portfolios, which we view as the best bulwark against severe losses in portfolio value. Still, we recognise that in another outbreak of political turbulence European assets could head down together, creating more downside for European-based investors that likely have greater exposure to such assets. With equity option pricing attractive from a historical perspective, we review hedging strategies that may be of interest to investors with defined spending needs, lower risk tolerance, and a view that the risks of a Eurozone breakup are severe enough to attempt to protect against.

What Are the Potential Risks?

European investors face several risks in the years ahead, including politics, potential policy missteps, and another economic downturn that exacerbates intraregional tensions. Political risks remain the most immediate concern, though the lack of structural reform that currently is curbing economic growth may be the bigger long-term threat for investors.

Politics. While the first part of the 2017 election cycle in Europe passed without event as elections in France, the Netherlands, Austria, and other countries resulted in victories for more centrist, pro-EU candidates, the gains of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party in September’s German election suggest populism retains some allure. The tensions that increase the odds of an extreme event continue to percolate beneath the surface. Many Europeans remain concerned over their economic fortunes, and unemployment remains elevated in many countries. Opinion polls show that voters also remain concerned about terrorism and immigration, explaining related support for more protectionist and nationalist platforms. The same polls also show only 42% of voters ‘trust’ the EU, though this is actually the highest level since 2010, when the sovereign debt crisis got fully underway.

Spain represents a different challenge for the Eurozone, and the long-simmering desire for more autonomy by many Catalans recently erupted via an independence referendum. There is no clear constitutional path to independence for Catalonia, and leaders in Madrid have a number of options to try to respond to a potential declaration of independence, including asserting more control over local institutions. The stakes are high for both sides; Catalonia contributes nearly 20% of Spanish GDP but also relies on the rest of the country for 35% of its exports. In the meantime, some companies are voting with their feet and moving their headquarters to other regions.

Subject to what happens in Spain, the next significant political flashpoint is probably the Italian election, which must occur by May 2018. An anti-EU party or coalition could emerge victorious and schedule an (ultimately successful) referendum on Eurozone membership. Italy’s use of the common currency would make this exit far more complicated than that being pursued by the United Kingdom, as the issue of outstanding debts and contracts that are euro-denominated would need to be resolved. A high-stakes game of poker between Italy and other Eurozone countries could ensue, with markets assuming the worst regarding topics such as redenomination of local debt and equities, resulting in a steep sell-off that ensnares assets across the region.

This outcome is possible but has recently seemed less likely. Italians are worried about their economic prospects and the related topic of immigration, but migrant flows have recently started to slow. Italians may lack trust in the EU, but this is different from wanting to leave. According to Pew Research, while 57% of Italians would favour having a referendum, 56% want to remain in the EU.[1]Dorothy Manevich, Bruce Stokes, and Richard Wike, ‘Post-Brexit, Europeans Are More Favorable Toward EU’, Pew Research Center, June 15, 2017. The leading populist parties seem to have accepted as much in recent months, with both the Five Star Movement and the Northern League backpedalling from earlier promises to host referendums.

For example, please see Wade O’Brien et al., ‘European Equities: Time to Focus on the Macro’, Cambridge Associates European Market Commentary, October 2013.

Further, and as we have written before, leaving the euro and launching a new currency is not a panacea for economic woes. It could boost exports and thus employment for a country, but a cheaper currency would lead to import-led inflation, and rising interest rates would make debt service more difficult. Investment might also stall given the resulting policy and economic uncertainty, as the new currency would trigger immediate capital outflows and could take several years to stabilize in value.

The ‘Brexit’ referendum last June served to remind at least some voters and politicians of the benefits of currency union and the merits of economic coordination. Eurozone leaders are now considering deeper economic integration across a number of areas, including schemes to further backstop failing banks and providing benefits to the unemployed during downturns. Recently, French President Emmanuel Macron has pushed for a pan-Eurozone budget that might fund a stabilisation scheme. However, prospects for such an arrangement are far from clear and possibly challenged by recent events in Germany and Spain. Political risks, while perhaps slightly diminished since the French election, have not gone away.

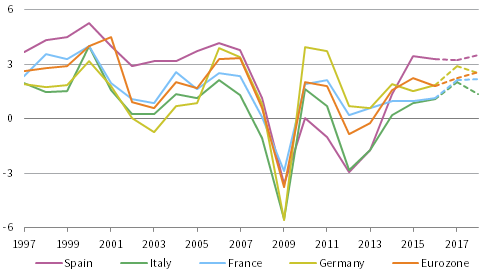

Policy Error. The European Central Bank (ECB) could also surprise markets in the months ahead by becoming unexpectedly hawkish. Despite slowing its pace of purchases this spring, the ECB’s balance sheet is still growing by around €60 billion/month and stands at €4.3 trillion (Figure 1). Low interest rates have been unpopular with savers and financial institutions for some time, and the ECB has recently acknowledged the pick-up in Eurozone growth. If the ECB tapers more rapidly than expected, or shocks investors by announcing a rate hike before the end of 2017, bond markets would likely be rattled and equities could also suffer. This event seems unlikely, and in any case, the repercussions could be short lived. A rate hike would probably only occur if growth and inflation were accelerating, which would provide offsetting benefits for earnings and thus equities. In the meantime, inflationary pressures remain limited, ECB President Mario Draghi has given few signals to question the status quo, and central bankers across the globe continue to carefully coordinate messaging and action.

FIGURE 1 GROWTH IN CENTRAL BANK BALANCE SHEET ASSETS

31 January 2007 – 30 September 2017 • Local Currency • 31 January 2007 = 0

Sources: Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

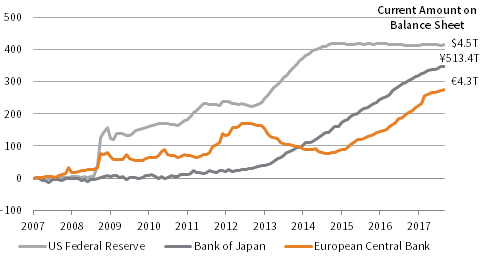

Economic Downturn. The improving macro backdrop may make it seem like an inauspicious time to discuss Eurozone tail risks. Eurozone GDP grew at a 2.6% annualised rate during second quarter, the 17th straight quarter of expansion and among the highest rates since 2010 (Figure 2). A combination of forces has boosted growth, including pent-up consumer demand as confidence rebounds; reduced fiscal austerity; increased credit creation; and a cheaper euro, which boosts demand for Eurozone exports. Encouragingly, growth has broadened out from traditional engines like Germany and is slowly gaining steam in countries like Italy.

Sources: Eurostat, France National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies, Germany Federal Statistical Office, Italy National Institute of Statistics, Spain National Statistics Institute, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Growth data are year-over-year percent change, except for dotted lines. Dotted lines show annualized 1Q 2017 and 2Q 2017 growth. 2Q 2017 growth data for Spain are estimates.

Yet, a closer look at some of the growth statistics raises some questions. Aggregate growth data mask a relatively weak recovery in some key Eurozone economies. This helps explain why almost 50% of Europeans still describe their own economic situation as ‘bad’, with the percentage far higher in France (72%), Spain (85%), and Italy (86%). Focusing on France, real GDP growth has averaged less than 1% for the past five years, and even this level of growth was built on shaky foundations. French government spending represents around 56% of GDP and sovereign debt/GDP has mushroomed by around 20 percentage points since the end of the 2011 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 GOVERNMENT DEBT-TO-GDP RATIO

First Quarter 2007 – First Quarter 2017 • As a Percent of GDP (%)

Source: Institute of International Finance.

Notes: Debt-to-GDP data are quarterly. Debt-to-GDP data for first quarter 2017 are estimates as of June 2017.

In a similar vein, while employment looks robust in Germany, it is far from healthy in some other countries. Italian unemployment – at around 11% – is almost double the level of a decade ago. Wage gains also look far from encouraging, possibly because many of the recently added jobs are in temporary or low wage sectors like tourism. ECB policies had been intended to depress the euro and boost price pressures, but the currency’s recent strength may threaten what muted inflation has been seen thus far.

Structural reforms would boost growth in many European countries, and lack of progress in this area arguably presents the greatest long-term risk to investors. In many countries, trimming labour forces during downturns is difficult, discouraging hiring. In others, bankruptcy laws can mean creditors take years to get control of assets, deterring lending. While progress has been made across the region in recent years, much work remains. The recent efforts of new French President Emmanuel Macron to push through labour market reforms could serve as interesting test of voter acceptance of these efforts.

Options for Concerned Investors

Investors worried that these risks could lead to an extreme outcome (like a country leaving or a total disintegration of the Eurozone) have a number of options including de-risking portfolios, using derivatives, and employing tactical underweights. Whether any of these options is right for the portfolio depends on the specific concern one is attempting to protect against, the investors’ risk tolerance, and other factors such as existing portfolio weights and tax status.

De-risking the Portfolio. Selling equities and moving to safe-haven assets like cash or sovereign bonds is one simple way to protect against a sharp equity market drawdown. Pursuing this strategy requires making several hard decisions, some of which will be driven by the specific thinking behind the de-risking. Concerns about an ECB policy error may mean an investor should sell equities and invest in short-dated sovereign bonds from a basket of Eurozone economies. However, those worried about politics – and maybe even a Eurozone breakup – may favour only a handful of highly rated Eurozone sovereigns as well as other safe-haven currencies like the US dollar, Swiss franc, and Japanese yen. Gold might also be considered.

Alternatives to fully de-risking also include strategies like long/short and event-driven hedge funds. Some long/short managers have nearly kept pace with the strong equity index returns of recent years while employing far less net equity exposure. Some event-driven and multi-strategy managers also employ hedging strategies, which might protect against a sudden spike in political risk, for example by shorting bonds issued by peripheral sovereigns.

Investors that choose to reduce their equity (and potentially credit) allocations should have a plan for re-risking portfolios. Choosing when to re-allocate to European equities could be behaviourally difficult under several scenarios, including one in which fears are realised and the market tanks, as well as a scenario in which one is wrong and markets become more expensive. De-risking portfolios by selling equities and trying to await a ‘safer’ re-entry point may mean investors misjudge risks or simply miss out on large short-term rallies, potentially making return targets unrealisable. To use just one example, despite the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis, the MSCI EMU Index has returned about 12% per year over the past five years and this performance has often been ‘lumpy’.

Using Derivatives. Investors can also use derivatives to hedge against possible downside risk. Implementation could take a variety of forms, depending on motivation. For example, taxable investors wishing to avoid capital gains may want to buy put options on equities, while tax-exempt investors could trim some positions but purchase call options to retain some upside potential.[2]Tax-exempt investors may also prefer puts, both to retain more upside but also to retain existing managers. This will prompt a number of additional decisions, including type of options (put, call, combination), timeframe, and strike (percent out of the money or sell-off to protect against). Hedging budgets may need to be determined, i.e., how much is one willing to spend trying to avoid downside risks?

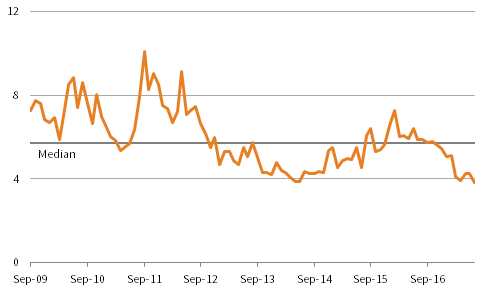

The good news for investors looking to hedge a Eurozone equity sell-off is that prices of all types of put options have become less expensive in recent months. In part, this is because recent market calm and thus realised volatility is influencing implied volatility in option prices. To cite one example, prices of 10% out of the money (OTM) 12-month puts on the Eurostoxx 50 Index have fallen around 35% over the past twelve months and now cost 3.8% upfront (Figure 4). The choice of tenor (maturity) option should be influenced by relative and absolute pricing, but also by when an investor thinks an extreme event might happen. For example, while pricing for six-month 20% OTM put options on Eurozone equities cost just 0.6% – almost half their cost one year ago – this may bring little comfort to an investor expecting volatility to tick up next summer. Pricing for short-dated options can be volatile, and thus buying them on a regular basis may present potential behavioural risks if volatility and thus costs were to suddenly spike.

FIGURE 4 EURO STOXX 50: 10% OTM PUT PRICES (1-YR EXPIRY CONTRACT)

30 September 2009 – 31 July 2017 • Percent (%)

Sources: BlackRock, Inc., STOXX Limited, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Investors could trim equity positions and sell OTM puts (forcing them to increase exposure when the market sold off) and at the same time buy OTM calls (providing upside if they were wrong and the market rose). Current pricing does not make the first leg of this strategy seem attractive, but buying call options might make more sense. At the end of July, 10% OTM one-year call options on the EuroStoxx 50 Index cost 1.2% upfront, down nearly 30% from June 30 and a 60% discount to their recent average.

Equity hedges are not the only tail-risk option. Holdings of euro-denominated corporate and sovereign bonds could be reduced, and a variety of options are available for hedging existing positions. Like equity options, fixed income hedges have also fallen in cost. For example, the cost of credit default swaps (CDS) to hedge against the Italian government defaulting on any of its bonds in three years has fallen to just 52 basis points (bps), down around 90% since its peaks during the Eurozone debt crisis (Figure 5). Hedging against a European high-yield bond market meltdown has cheapened by an even larger amount – buying protection on the three-year iTraxx Crossover Index now costs 163 bps, after exceeding 800 bps in late 2011.

FIGURE 5 EUROPEAN 3-YEAR CREDIT DEFAULT SWAP SPREADS

31 December 2007 – 30 September 2017 • Mid Spread (bps)

Sources: Markit Economics, J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Note: European IG Credit represented by iTraxx Europe Main 3-Year On The Run Index and European HY Credit represented by iTraxx Europe Crossover 3-Year On The Run Index.

* Scale capped at 900. European HY Credit peaked at 1,245 on 27 February 2009.

Offshore investors could also consider hedging the currency exposure embedded in their Eurozone equity holdings. Such hedges could serve two purposes: to reduce overall equity portfolio volatility on an ongoing basis, and to help cushion the portfolio during an extreme currency sell-off. Given the euro’s sell-off in recent years and current depressed valuation, however, it is not clear if another outbreak of political or other disquiet could trigger the same exchange rate volatility as was seen either in 2008 (when the euro started the year trading around $1.50) or even at the end of 2011 (the euro was near $1.40 that October).

Derivatives can offer several benefits, including allowing investors to retain some skin in the game, maintain commitments to high-quality managers, and limit tax liabilities (if keeping positions but buying puts). Selling puts can also force investors to ‘lean in’ and buy stocks when valuations improve. Equity options have recently improved in price, with call options in particular looking inexpensive relative to their histories.

Still, derivatives present several challenges. One is behavioural: will investors have the stomach to buy defensive put options just when they might be needed most? The same 10% OTM put options that cost around 4% today cost around 6% as recently as last November, and over 10% at the depths of the sovereign debt crisis. Another is more technical: does the investor have the staff and technology to monitor option pricing and implement desired hedges?

Despite improved pricing, current option pricing might still not be a bargain. History has shown that the type of extreme outcomes investors might want to hedge against are fairly rare, and buying options is likely to weigh on long-term performance. Over the past 30 years, only 14% of all trailing one-year returns on the MSCI EMU Index have been less than –15% (the point at which a 10% OTM put purchased for 5% would break even), though 47% of these returns have been greater than 15%. Looked at differently, paying current prices (3.8% upfront) for a 10% OTM put option on Eurozone stocks, if done on an annual basis, would generate a substantial drag on future returns. Eurozone stocks have only returned around 8% annualised over the past three decades.

Employing Tactical Underweights. Investors also have the option of simply reducing their exposure to Eurozone equities in favour of equities from other regions (both developed and emerging). Investors pursuing this option should be mindful of any currency risk being taken on and the resulting risk (volatility) being added to the portfolio. Some investors may also have investment policy statements or asset allocation targets that prescribe minimum weightings for European (or regional) equities, which would need to be followed or amended. Most importantly, investors should consider the prospects for other regions, and their valuations.

See, for example, the analysis in our annual report ‘Decades of Data’.

Underweighting Eurozone equities in favour of regions with seemingly better political or economic prospects raises several issues. If the concern is slower growth, it is worth noting that historically there has been relatively limited correlation between GDP growth and equity returns. This is especially so in markets where many companies are export oriented. If the concern is political risk, underweighting Eurozone equities in favour of another region may provide limited protection in a broad-based market sell-off. Eurozone equities did underperform during the depths of the Eurozone crisis in 2011, but lower absolute valuations for other regions were then more supportive. Specifically, in January 2011, US equity valuations traded at 13% above their historical median; today they trade 45% above that level. In contrast, current valuations for Eurozone equities (Figure 6) are only 7% above their historical median. Weak Eurozone earnings and growth in recent years help explain current valuations. Still, a low bar means that earnings growth expectations for 2017 are robust, and stronger earnings could be the catalyst that pushes the market higher.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: World represented by the MSCI World Index, Eurozone by the MSCI EMU Index, United Kingdom by the MSCI UK Index, and United States by the MSCI US Index. The composite normalized price-earnings (P/E) ratio is calculated by dividing the inflation-adjusted index price by the simple average of three normalized earnings metrics: ten-year average real earnings (i.e., Shiller earnings), trend-line earnings, and return on equity–adjusted earnings. History for composite normalized P/Es begins: January 1970 for World, April 1998 for Eurozone, and December 1969 for United Kingdom and United States. Median value forward P/E based on data from June 2003 to present. CPI data are through 31 August 2017.

Conclusion

Investors can be forgiven for casting a wary eye on Eurozone assets given the potential for more volatility around recent events in Spain and the Italian elections next spring. Still, we think the likelihood of another serious outbreak of Eurozone political distress is low. Opinion polls show most voters across the block firmly want to remain in the European Union, and a number of political parties are trying to back away from earlier populist promises. These politicians may be more economically literate than is often assumed, and even when they are not, the still-unfolding situation in Catalonia indicates business leaders are not afraid to step in and underlines the risks of breaking from the status quo. The risk of a large country defaulting on its debt also seems limited, given tools the ECB can employ like quantitative easing and the ease of servicing debt, when interest rates are set at zero.

Investors looking to hedge against some extreme Eurozone risk should also consider recent history, as authorities can be extremely resourceful when trying to stave off a sovereign default. When legal or technical obstacles to action have arisen, they have typically been changed via the legislative process or circumnavigated.

Even if an extreme tail-risk were to occur, hedging against such a risk might prove difficult for several reasons. Timing such an event is nearly impossible, and the costs of hedges would likely soar as more information became known, making the risk/reward less attractive. In the meantime, investors might find it hard to stomach paying a significant share of their returns away every year for portfolio insurance, and moving to cash (or other safe havens) might make covering spending more difficult. History has also shown that authorities at times can look unkindly on hedging strategies, and instruments such as CDS may be outlawed just when they are needed most.

That said, several current strategies do currently look attractive on a relative basis to make portfolios more defensive. Tax-exempt investors could trim equity positions and buy equity index call options, offering protection yet upside if stocks were to rise. Buying protection against a breakdown in corporate fundamentals via the CDS market is much cheaper today than historical averages and peaks seen during prior periods of distress. Finally, for offshore investors, currency hedging at least some equity exposure provides an evergreen benefit of reducing overall portfolio volatility.

Still, we believe the best thing investors can do to protect against downside risk is keep the same types of diversified portfolios they presumably already have, relying on safe-haven assets during periods of turbulence to fund spending and also provide some dry powder when sell-offs mean valuations improve.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Joseph Comras, Senior Investment Associate

Footnotes