At most endowments, the majority of the long-term portfolio is invested in public equity and PE/VC. On average for the overall C&U universe, about 63% of the long-term investment portfolio (LTIP) was allocated across these categories at the end of fiscal year 2024. The combined average allocation does not vary much across different asset sizes, ranging from a low of 59% for the $500 million to $1 billion subgroup to a high of 65% for the $200 million to $500 million cohort. However, the breakdown of allocations between public and private equities does look quite different when going up or down the portfolio size spectrum.

Generally, smaller endowments continue to have the highest public equity allocations, while larger endowments have higher private allocations (Figure 19). For endowments less than $200 million, public equities made up 51% of portfolios, on average, while PE/VC accounted for just 12%. In contrast, the average breakdown was nearly even across the two categories for endowments greater than $3 billion. The largest endowments allocated an average of 30% to public equity and slightly more (32%) to PE/VC.

There were also distinct differences elsewhere when comparing asset allocation structures across the asset size groups. Smaller endowments tend to allocate more to bonds, with an average allocation of nearly 13% for endowments less than $200 million. This was about three times what the average fixed income allocation was for endowments greater than $3 billion. Conversely, the largest endowments allocate more to real assets and inflation-hedging strategies, with an average of 11% invested, compared to less than 4% for the smallest endowments. The bulk of real assets allocations for larger endowments came from private investment strategies. Hence, the differential in illiquid allocations between large and small endowments is even wider than what is shown in the PE/VC category alone.

Asset Allocation Trends

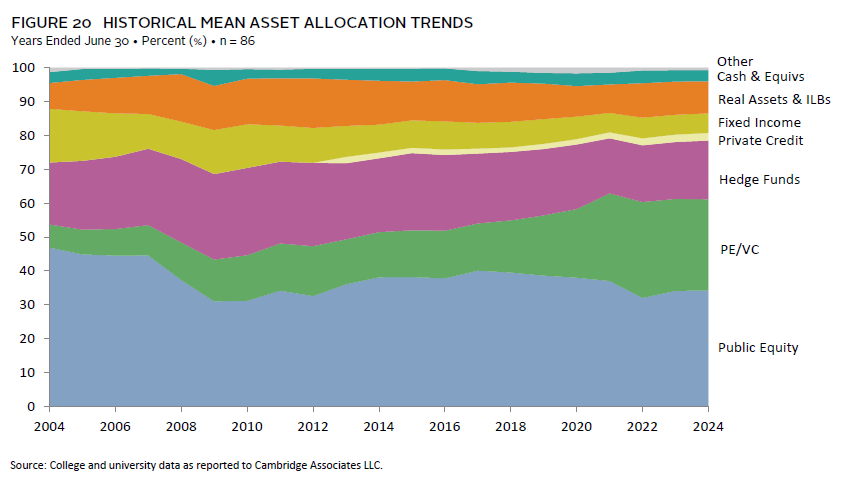

Over the long term, the key trend in endowment investing has been the increase in private equity allocations. Figure 20 tracks the trend in average portfolio allocations for a group of 86 C&Us that have participated in each of our annual surveys over the past two decades. The average PE/VC allocation for this constant group has nearly quadrupled, rising from 7% in 2004 to 27% in 2024. This shift has largely been funded by diversifying out of public equities, with average allocations declining from 47% in 2004 to 34% in 2024. However, this decrease in public equities alone does not account for the entire increase in PE/VC. Average fixed income allocations have declined substantially over this period from 16% to 6%. The result is that the portfolio risk profile at most endowments is more equity-oriented today than it was two decades ago.

Examining only the beginning and ending points of this period overlooks changes that occurred in between. For instance, allocations to hedge funds and real assets in 2024 are within a few percentage points of their 2004 levels. However, both categories experienced steady increases in the early years of this era before trending downward for most of the remaining years. The average hedge fund allocation peaked at 26% in 2010, while real assets allocations reached a high of 15% in 2012.

Notably, there have been some shifts in allocations in recent years that diverged from the long-term trends. The average PE/VC allocation peaked at just more than 28% in 2022 but has since declined slightly. Meanwhile, public equity and hedge fund allocations saw minor increases over the last couple of years. One challenge in analyzing short-term asset allocation trends is distinguishing between changes driven by market movements and those resulting from intentional allocation adjustments. For example, the outperformance of public equities compared to private equities in recent years could naturally lead to some shifts in the weightings of those strategies, as already noted. Are these changes primarily driven by the market dynamics or are endowments reducing new private equity commitments and perhaps even selling off existing investments?

While the precise details are difficult to ascertain through our survey data, information we collect on target asset allocations can be insightful in understanding where endowments might be modifying their policies going forward. Despite the slight decrease in actual PE/VC allocations over the past two years, a significant number of endowments continue to raise their targets in this category (Figure 21). Over the past year, nearly one-quarter (23%) of respondents increased their target to PE/VC, while only 4% reported a decrease. In contrast, for public equity and hedge funds—where actual allocations have recently ticked up slightly—more endowments reported decreases to their targets in 2024 than increases. These data suggest that the recent changes in average asset allocations are mostly attributable to market dynamics and the natural effects those have on portfolio holdings.

Portfolio Liquidity

See the Institutional Support section for more analysis and commentary on spending and net flows.

Liquidity management is a key issue that endowments need to be cognizant of. Traditionally, the biggest liquidity need for endowment portfolios has been meeting their annual spending policy distributions. The median effective spending rate for C&U peers tends to be between 4.5% and 5% in most years. While new gifts and inflows can help offset some of this spending from a liquidity management perspective, ensuring adequate liquidity for annual distributions remains a key objective for endowments.

Approximately half of respondents have formal liquidity policies outlined in their investment policy statements. Another one-quarter of respondents have informal guidelines for liquidity considerations. Liquidity policies often include requirements for how much of the portfolio can be converted to cash within a specified number of days. Additionally, liquidity guidelines may establish limits on the percentage of the portfolio that can be invested in assets deemed illiquid. It is not uncommon for endowments to include unfunded commitments in these liquidity measures. Unfunded commitments represent capital that has been committed but not yet paid into private investment funds (Figure 22).

The dollar amount of unfunded commitments can be equivalent to as much as 25% or more of the portfolio’s current asset size at some endowments. On the other hand, at some smaller endowments, these commitments can be relatively small compared to the size of the investment portfolio. For endowments with assets greater than $1 billion, the median ratio of uncalled capital–to-LTIP market value was 16% at the end of fiscal year 2024. The ratio was just slightly lower (12%) at endowments with assets less than $500 million. However, when considering a measure that combines unfunded commitments with actual private allocations, these ratios were generally much higher at larger endowments compared to smaller peers.

Distributions from existing private investment funds can serve as a source of funding for new capital calls. However, when these distributions fall short, institutions must find additional liquidity to meet new capital calls. This was a common experience among endowments in fiscal year 2024. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of respondents reported that their private investment programs were cash flow negative, meaning the amount of distributions from private funds was insufficient to cover the new capital paid in (Figure 23). The experience was similar across both larger and smaller endowments, with the majority of respondents in each asset size cohort reporting the same outcome.

This was the second consecutive fiscal year that endowments have faced this scenario. In 2023, a nearly identical percentage of respondents (71%) reported that new capital calls were greater than distributions. This ongoing challenge underscores the importance of establishing appropriate liquidity management guidelines and strategies, particularly in when it comes to tracking and monitoring the illiquid bucket of the portfolio.

Portfolio Implementation

Endowments primarily use external investment managers to implement their portfolio allocations. The number of managers employed by an endowment is largely influenced by the scale of total assets under management. Larger endowments, which have more capital to deploy, naturally maintain more manager relationships compared to smaller portfolios. In addition, allocations to private managers are typically less concentrated than manager allocations in public asset classes, leading to a greater number of manager relationships for portfolios where private allocations are higher. The median number of managers employed by endowments greater than $3 billion was 145 at the end of fiscal year 2024. In contrast, the median was fewer than 30 managers for the subgroup of respondents with assets less than $200.[1]Further data on the number of managers used for specific asset classes can be found in the Appendix section of this study.

Some interesting trends emerged from a constant group of endowments that provided manager data going back to 2019 (Figure 24). For each asset size cohort, the median number of managers in 2024 was higher than the median from five years ago. However, many larger endowments have reduced the number of manager relationships in more recent years. For endowments with assets greater than $3 billion, the median number of managers peaked in 2021 but has declined each year since. Similarly, the median for endowments with assets between $500 million and $1 billion has declined slightly since 2022. Looking back over the past year for all C&Us in this analysis, slightly more than half (51%) of endowments reported more managers in 2024 compared to 2023.

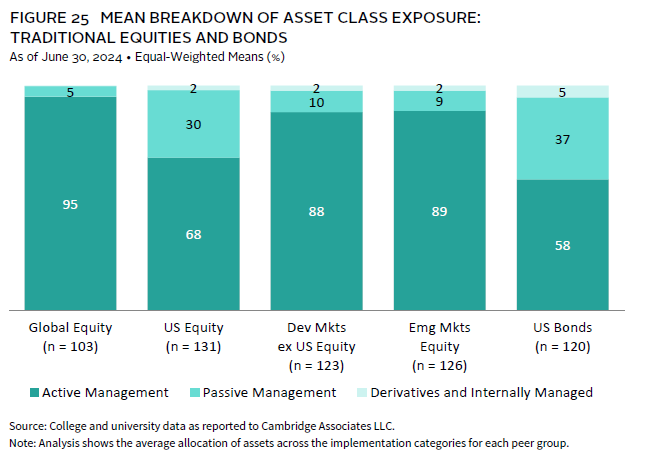

The overwhelming majority of allocations to public asset classes is invested via external managers, while just a small percentage of these strategies are internally managed. Most external allocations are implemented through actively managed funds and strategies, and this experience is consistent across different asset sizes. However, US equity and US bonds are two asset classes where the use of passive management and index funds has gained more traction over time (Figure 25). On average, 30% of US equity allocations were managed through passive vehicles in 2024, notably jumping up from 25% the previous year. Ten years ago, the average for our survey group was even lower at 19%. Similarly, passive management for US bonds accounted for an average of 37% of endowments’ asset class exposure at the end of fiscal year 2024. This was slightly higher than the average of 34% from the previous year and represents a substantial increase from 20% in 2014.

In private investments, endowments also implement most of their allocations through external managers (Figure 26). However, the types of funds used can vary based on the portfolio’s asset size. Smaller institutions tend to rely more on fund-of-funds compared to larger peers, particularly in venture capital and private natural resources. For endowments with assets less than $200 million, fund-of-funds make up the majority of the average allocation to these strategies. In contrast, fund-of-funds represent only a small fraction of the average allocations for endowments with assets greater than $3 billion.

Larger endowments are more likely to have direct private investments, although these typically account for 10% or less of average asset class exposure. Endowments that have the resources and expertise to manage direct investments effectively can take advantage of deals they find particularly attractive and save on higher fees that are charged through the traditional limited partner (LP) fund structure. Most direct investments reported by endowments are actually co-investments made alongside a general partner. Some endowments also engage in direct “solo” investments, where the transaction is originated and managed independently by the endowment itself.

Footnotes