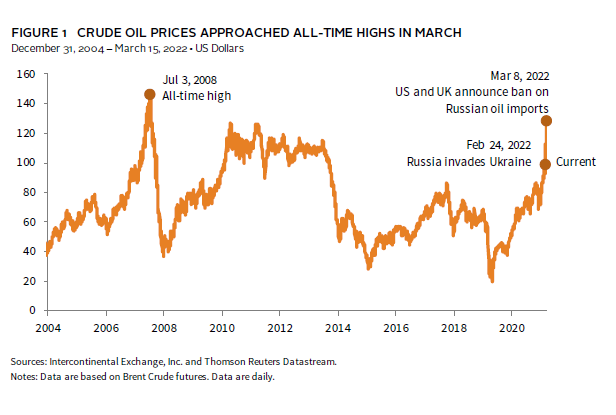

Oil prices spiked earlier this month as Russia’s supply was disrupted due to sanctions stemming from the country’s invasion into Ukraine, making an already tight market even tighter. Prices briefly surpassed $130/barrel in early March, the highest since July 2008. Pressure on prices has abated in recent days, but significant uncertainty remains. Barring a resolution to the military conflict, balancing the oil market in the coming months will depend on the following: OPEC increasing supply, Western allies striking a deal with Iran and/or Venezuela involving the easing of oil export sanctions, major energy consumers outside the United States and Europe (such as India and China) stepping up their imports of Russian crude, and—to some extent—demand destruction. Today’s events may also be the impetus for redrawing the energy landscape over the next decade.

Why Are Oil Prices so High?

Oil markets were already tight leading into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, due to a combination of resurgent demand driven by fiscal and monetary stimulus, lagging production, and relatively low and declining inventories.

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the West has used financial sanctions to economically isolate Russia, exacerbating the supply/demand imbalance in oil markets. On March 8, both the United States and United Kingdom announced bans on Russian oil imports, contributing to a spike in prices. However, many Western-based companies had already been avoiding Russian oil since the beginning of the invasion. For context, Russia typically exports 7–8 mb/d of crude oil and has seen a shortfall of 3 mb/d so far this month, representing one of the largest oil disruptions since WWII.

How Might This Supply Gap Get Resolved?

There are various potential supply sources to compensate for foregone Russian exports. First, led by the United States, the 31 members of the IEA are collectively releasing 60 mb from their emergency reserves. This short-term solution will likely last a few weeks.

Longer term, core OPEC countries could plug much of the supply gap, but it would require a several-month ramp up period and OPEC has so far refrained from making any commitments to do so. One major hurdle is a frayed relationship between the Biden Administration and the Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who has thus far declined to speak to the United States. The United States is pursuing deals with both Iran and Venezuela that would involve easing oil export sanctions for the OPEC member nations, though Goldman Sachs estimates it would take at least six months to partially ramp up production, and talks have stalled.

Meanwhile, US domestic shale producers have pushed back on political pressure to expand production, citing shareholder concerns over increasing long-term investments amid an uncertain profitability outlook. In recent years, investors have directed shale producers to adopt a less reactionary drilling strategy. Given shortages of labor and equipment, ramp up times for new drilling projects are currently ~18 months. In this time frame oil prices may already have declined from today’s elevated levels, which could lead to significant losses. However, a more sustained supply deficit could compel shale producers to make these capital expenditures.

Finally, buyers outside of the United States and Europe, such as India and China, could play a critical role in a supply re-alignment by soaking up much of the excess Russian crude, freeing up more of OPEC’s oil for the West to consume. India has recently stepped in as a potential buyer of Russian crude. Meanwhile, China also has the capacity to step in as a buyer, but it would require some costly supply-chain reconfigurations and involve significant lead times due to the lengthy shipping routes. Further, China may be reluctant to increase imports from Russia, at least initially, at a time when Russia is becoming a “global pariah.” Notably, there are no reports of increased Chinese purchases of Russian crude. Similarly, China did not scale up oil imports from Iran or Venezuela in recent years amid Western sanctions. Indeed, a major risk for any potential buyer of Russian crude is the prospect of facing the West’s consternation.

The Outlook and Implications

The futures market is currently betting that supply/demand will begin to come back into balance in the coming months. As the price of oil spiked, the futures curve went into extreme backwardation with six-month ahead futures as much as $19 lower than front-month futures on March 8—implying sub-$100 oil.

However, as discussed, a lot needs to go right for oil markets to balance out. If markets lose confidence this will happen, then it could send prices higher again. In such a scenario, sustained higher oil prices would contribute to inflationary pressures and at extremes could be a drag on growth. It is difficult to say how expensive oil would need to be to cause so-called “demand destruction.” It is worth considering that, in inflation-adjusted terms, oil prices exceeded $100/barrel from 2010 to 2014, peaking at $160/barrel, but never impeded consumption growth. Further, the efficiency of oil use has improved over the years, such that in the early 1970s 1.1 barrels of oil was required to produce $1,000 worth of real GDP, while in 2017 it only took 0.4 barrel.

Regardless of how the supply and demand balance evolves, today’s events may be the catalyst for a dramatic reshaping of the energy landscape. The EU is developing an energy roadmap to mitigate reliance on Russia. Meanwhile, tides appear to be shifting toward an expansion of domestic oil production in the United States. If OPEC does not step up to plug the supply gap from Russia, conditions will support tighter oil markets, potentially creating incentive for shale producers to invest in bringing more supply online. In the long run, this situation underscores the need for energy independence and should reaffirm the West’s commitment to invest in renewable energy sources and technology development.

Joe Comras, Associate Investment Director, Investment Strategy