See Eric Winig and Peter Mitsos, “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do,” Cambridge Associates Market Commentary, April 2009.

Seven short years ago, we published a paper making the case that although structural forces could, if left unchecked, eventually undermine the euro, the common currency was “currently proving more beneficial than costly to member countries, and thus there is no substantive constituency that supports a breakup.” The question in the “Brexit” aftermath, of course, is whether such reasoning still holds.

While the first part is open to debate, the second has clearly shifted, as the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union (EU) seems just the leading edge of deep dissatisfaction—and even outright anger—with EU policies, rules, and member requirements across the Continent. While immigration policies are clearly part of this, those who focus on the immigration aspect to the exclusion of other factors (e.g., the failure of many people to participate in the economic “recovery,” and a sense of being governed by “unelected elites”) are missing the broader implications of Brexit.

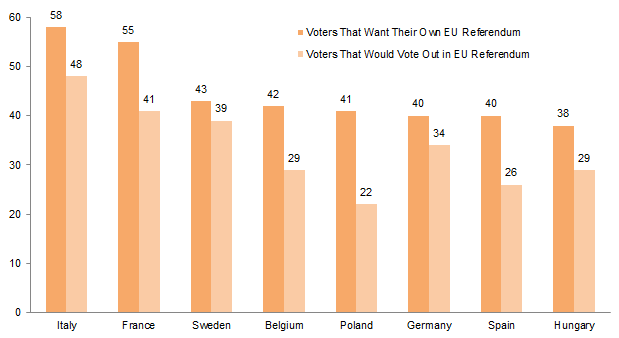

Thus, while many commentators seem ready to dismiss opinion polls that show strong support for leaving the EU in several countries—especially surprising given the “unexpected” Brexit result—we are less sanguine. The risks of real departures from the Eurozone no longer seem so remote.

Sources: Barclays and Ipsos Mori.

If History Is a Guide . . .

There is no surer way in the investment world to invite mockery than to claim “this time is different.” And it is true the euro has survived recent “existential” crises with nary a scratch. The question, then, is whether and why we should consider Brexit different from these events, which, while occasionally causing significant short-term angst, have done little to change the general narrative that the EU, and hence the euro, is solid and here for the long haul. Examples include the 2012 European debt crisis, the periodic panics over “Grexit” (the most recent of which was only one year ago), and the pressures that have come from finding ways to support other weak members (Portugal, Italy, Spain, and even France).

Yet none of these issues ever truly constituted a “crisis,” headlines at the time notwithstanding. In retrospect it seems obvious the European Central Bank (ECB) would do “whatever it takes,” or that Greece couldn’t really leave the EU even if it wanted to, or that political flare-ups would do little to imperil the ability of, say, Italy to borrow money at rates below those of countries with better economic profiles.

The difference between earlier situations and Brexit, in our view, is that those outcomes ultimately rested in the hands of a small cadre of individuals who each wanted the same thing—a resolution. Further, this sentiment was widely shared among investors and the “man on the street,” most of whom bought into the narrative that what was good for banks and large investors was ipso facto good for the economy at large. Thus, when ECB president Mario Draghi said he would do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro, or Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras agreed to a bailout after Greek voters emphatically rejected it, investors were soothed since they (rightly) assumed the people pulling the levers were on their side.

The Greek case is particularly instructive, as it represents a similar scenario to Brexit in that voters opted out of the current system. However, the economic situations for the two countries could hardly be more different. For example, when an analyst said in early 2015, “If Grexit is as bad as we think it is, there will be few who want to imitate it,” this not only reflected the conventional wisdom among commentators, but also resonated with Greek citizens watching unemployment skyrocket and banks restrict ATM withdrawals.

Britons, on the other hand, may justifiably look round and wonder what all the fuss was/is about. Indeed, while much of the “remain” campaign centered on telling people it would be economically disastrous to leave the EU—as, in one memorable phrasing, the country would “go to the back of the queue” for trade deals—such assertions are already being walked back, as the absurdity of not trading with Britain as an independent entity sinks in.

The most striking part of the Brexit result was the juxtaposition of overwhelming support for “remain” among analysts and commentators and its summary rejection by voters. This was summed up both by now-former UK justice minister Michael Gove’s comment that “people in this country have had enough of experts,” and, arguably even more so, by the vote’s near-universal panning from . . . experts. Many have noted that a growing swath of people believe the global economic order, as currently constituted, is something of a scam that exploits workers for the benefit of owners of capital. Whether those with this view are “right” is beside the point; given this predilection, every data point is either proof of their thesis, or part of a scare tactic. In other words, the reason voters didn’t care about warnings that a vote to leave would roil markets and tank the economy was they either (a) didn’t believe it or (b) didn’t care. When you believe the system is rigged, you’re less concerned with the fallout from blowing it up.

Brexit Contagion

See Aaron Costello and Han Xu, “Has the GBP Bottomed? Not Likely,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, July 20, 2016.

Indeed, while much of the focus in the wake of Brexit has been on the potential impact on the UK economy, one can make a case that the EU is more at risk—British fortunes may now be inversely linked to those of the EU. In the event that Brexit leads to a broad fracturing of the EU, for example, we would expect British trade and the pound to benefit. As we state in another research brief, “the worst-case scenario for Europe may prevent the worst-case outcome for the United Kingdom.”

Of course, the consequences of Brexit could be contained under at least two scenarios:

- Brexit doesn’t actually occur. This was the odds-on favorite of most commentators in the wake of the vote, but seems more a coin flip at this point. Such an outcome could lead to further unrest if it were viewed as subverting the will of voters—but it would, ceteris paribus, allow a continuation of the status quo.

- Brexit occurs, but there is no spillover to other EU countries. This seems to us the least likely scenario, but after the Brexit result there can be little doubt “remain” campaigns elsewhere will take nothing for granted, and the EU is keenly aware of how closely what is negotiated with Britain will be watched. Similar to the “no Brexit” option, this would allow things to remain more or less as they are.

Investment Implications

Brexit fits into a broad narrative where policymakers have for some time focused their efforts on propping up risk assets—with the stated goal that such actions would “spill over” into the economy by boosting spending—even as such policies dramatically widened the gap not only between rich and poor, but also between rich and extremely rich. While we and others have commented on this phenomenon from time to time, Brexit seems a shot across the bow from the people not benefiting from such policies.

Clearly a full-fledged revolt (i.e., further countries voting to withdraw from the EU) would be disastrous for risk assets—or would it? Regardless of one’s views on the merits of the EU, the past few weeks have been instructive in the likely response of policymakers to further turmoil—according to Citigroup’s Matt King, we have seen “a surge in net global central bank asset purchases to their highest since 2013.”

Risks remain binary. Either the system will hold together—in which case assets such as richly priced equities and high-yield bonds will likely continue to rally—or it (and they) won’t. Our advice on how to navigate this environment hasn’t changed—seek out quality, make sure you are getting compensated for risk taken, and favor assets with true diversification (i.e., different economic bases of return).

We also continue to like the prospects for gold, as perhaps the most predictable feature of the current system is that central banks will continue to move out their own risk curve. The past few weeks have seen several open discussions of “helicopter money” by very prominent central bankers, both current and former, and absent some sort of economic miracle, this remains the most likely endgame.

The Bottom Line

Investors should take seriously the prospect that Brexit is different from the crop of recent crises. It’s easy to see the connections between Brexit, the success of Donald Trump’s candidacy in the United States, and the popularity of European politicians singing from the same hymnal. As Arnaud Montebourg, François Hollande’s former minister of the economy and a possible presidential candidate, recently told Le Monde, Brexit “is a shock for Europe, but a foreseeable one. For 20 years, every time the people have been consulted, they have expressed their rejection of the construction of Europe as it has been imposed on them. . . . The construction of Europe as it has been done is anti-democratic.”

The Brexit vote is the first time voters in a developed country were asked to opine in a material way on the merits of the current global financial system and they voted “nay.” Yes, immigration and nativist sentiment played a role, but the economic source of these worries should not be forgotten. Further, while it is still early days, at least some of the scare stories circulated by the “remain” camp will turn out to be overblown, which will provide yet another data point for those already leaning toward dismissing such warnings.

Whether or not the Eurozone is still “proving more beneficial than costly to member countries,” there is now, in stark contrast to 2009, a substantial (and growing) constituency that supports a breakup.

Eric Winig, Managing Director