Asia has a structural and cyclical need for alternative credit providers; given where Asia is in the credit cycle, special situations and direct lending strategies should offer attractive risk-adjusted returns

- Returns for traditional Asian fixed income and credit are unattractive today. However, opportunities remain in the less liquid, underserved, and complex spheres of corporate lending in Asia.

- Special situation and direct lending funds are a way to circumvent some of the pitfalls of private equity investing in Asian markets. Such funds will not deliver typical private equity returns of 2.5x to 3x at the fund level, but if carefully structured in the hands of a skilled manager, they can achieve a stable 1.5x to 2x with the potential for more, and in a shorter time frame.

- If the credit cycle fully turns and macro conditions deteriorate, the opportunity set and return potential for alternative credit in Asia will only broaden. By identifying skilled managers now, investors can prepare for the eventual emergence of a distressed cycle in Asia over the next few years.

- Given the complexity and legal/regulatory risks associated with investing in Asia, manager selection is of the utmost importance. Investors should focus on managers with clear expertise and ample resources to both source and properly structure deals.

As economic growth slows across Asia and the credit cycle begins to turn, both local and foreign banks have tightened their lending to the region, exacerbating existing structural issues of limited funding for small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). This presents an opportunity for specialized investors to propose alternative credit solutions to bridge the lending gap. Such investments have the potential to generate stable, low-single-digit return multiples with downside protection, making them attractive in today’s uncertain market environment.

This research note will introduce the different types of alternative credit strategies being implemented in Asia, with a focus on special situation and direct lending managers, which we view as offering attractive risk-adjusted returns in the current market environment.

What Is Alternative Credit?

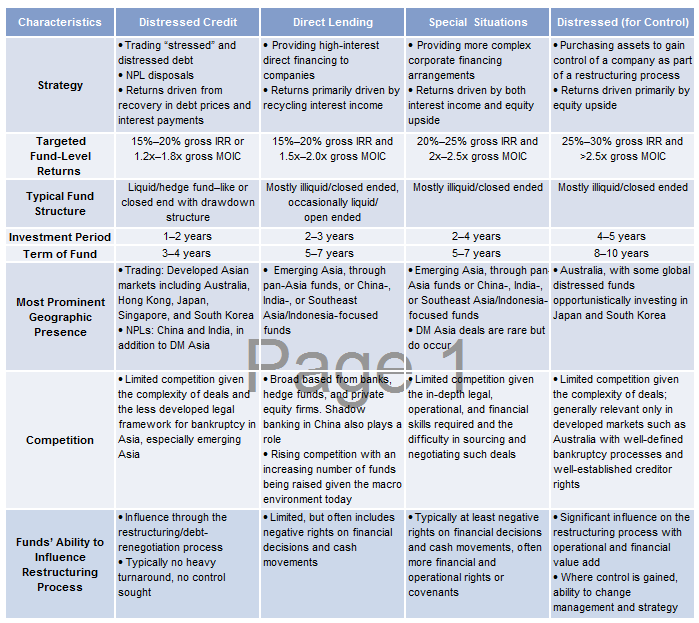

This piece focuses on “alternative credit” opportunities, which are distinct from “traditional credit” opportunities such as investment-grade and high-yield bonds or other liquid strategies centered on fixed income and currency trading. Alternative credit encompasses a wide range of strategies, which we have grouped into four broad categories:

- Distressed Credit. Investing in “stressed” and distressed debt at a discount to reap gains as a result of eventual recovery. There are two main sub-strategies: distressed trading, which focuses on publicly traded debt, and non-performing loans (NPLs), which focus on acquiring bad loans from financial intermediaries.

- Direct Lending. Making direct loans to companies, usually structured with downside protection mechanisms and collateral. Interest income is the primary return driver.

- Special Situations. Providing more complex financing arrangements to companies, where returns are driven by both interest income and equity upside.

- Distressed for Control. Buying distressed financial assets to gain control of a company and benefit from a restructuring process, with returns generated primarily through equity upside.

It is worth noting that these strategies typically use limited fund- or deal-level leverage.

Given the overlap among distressed credit, direct lending, and special situations, many managers combine or migrate across these strategies as opportunities emerge throughout the credit cycle. Distressed for control is a more distinct strategy, in which equity upside tends to be the primary driver of returns, and a skill set in operational value add is needed for success. Figure 1 provides additional detail on the characteristics of these investments. As noted in the table, target returns range from gross internal rates of return (IRRs) of 15% –20% for distressed credit and direct lending to 20% –25% for special situations to 30% for distressed for control funds. Figure 2 is a stylized illustration of where these strategies fall on a risk/return spectrum.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Source: Cambridge Associates.

Note: The blue circles represent traditional credit asset classes while the orange circles represent alternative credit strategies.

Where Are the Opportunities Today?

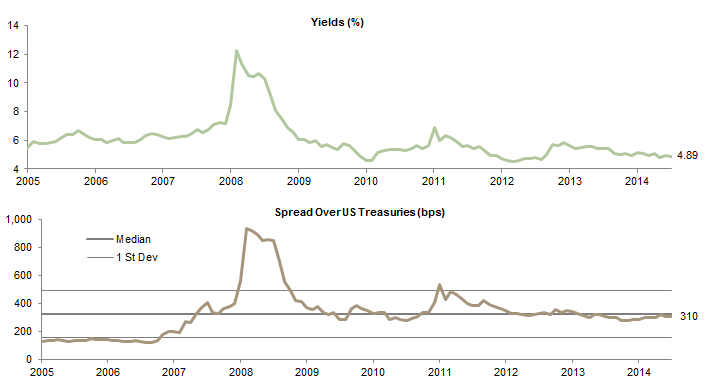

Investors today have limited opportunities in traditional Asian fixed income, as yields remain near record lows and credit spreads near historical averages, including for high-yield bonds (Figure 3). This reflects not only global investors’ search for yield, but the ability of large public companies and quasi-sovereign issuers to tap international bond markets. However, opportunities in the less liquid, underserved, and complex spheres of corporate lending in Asia are increasing. Indeed, there is a structural need for alternative credit providers in emerging Asia, created by inefficiencies in underdeveloped capital markets. Given where Asia is in the credit cycle, we consider the special situations and direct lending strategies to be more compelling.

Sources: J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Asia corporate bonds are represented by the J.P. Morgan Asia Credit (corporate) Index (JACI), which includes both investment-grade and high-yield bonds.

Market Background. SMEs have much more limited access to credit via the banking sector or public markets due to regulatory and behavioral constraints on bank lending in economies such as China and India that channel lending to state-owned entities at the expense of the private sector. Survey data from the World Bank indicate that 50% to 60% of “medium-sized” firms in China, India, and Indonesia are underserved by the banking system compared to only 29% to 35% in high-income OECD countries.[1]Based on data from the IFC/World Bank MSME Database and McKinsey & Company’s 2012 report, “Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Emerging Markets; How Banks Can Grasp a $350 Billion … Continue reading At the same time, debt and equity capital markets are not as deep nor as liquid as their developed markets counterparts. Some firms either cannot meet the hurdles to list or face the prospect of becoming a poorly traded stock with a significant valuation discount, while local corporate bond markets serve only the largest issuers.

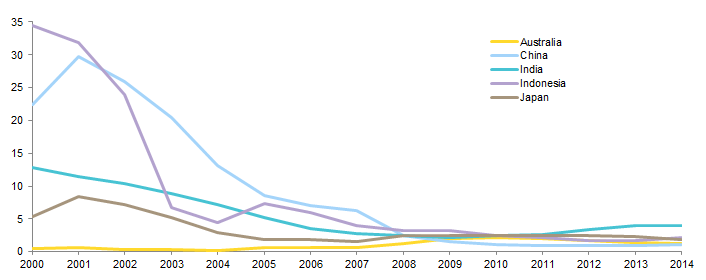

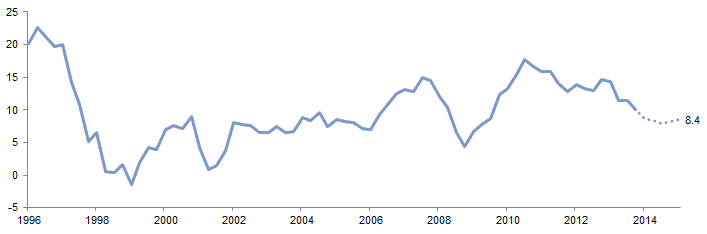

In addition to these structural issues, cyclical factors are also in play. Credit growth across Asia has slowed (Figure 4) alongside GDP growth. At the same time, North American and European banks have withdrawn from Asia in the aftermath of the global financial crisis as they focus on reducing their balance sheets. Equity capital markets have also disappointed and remain partly closed to smaller companies, while debt financing has become more costly for certain sectors, such as property developers and companies in the commodity and especially oil & gas sectors. Finally, fund flows to Asia have slowed amid concerns over Federal Reserve tightening and eventual interest rate hikes.

Figure 4. Median Asia Private Sector Loan Growth

Fourth Quarter 1996 – Fourth Quarter 2015 • Year-over-Year Percent (%) Change

Sources: Oxford Economics and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Asia is defined as China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. Data from fourth quarter 2014 are forecasts.

The combination of structural and cyclical pressures creates an opportunity for investors willing to provide capital and bear liquidity risk. Figure 5 shows a stylized version of the credit cycle. Asia has passed the peak in credit growth but is not quite fully in an economic downturn with rising defaults, placing Asia today in the upper right segment of our stylized cycle. While many central banks in Asia are now easing monetary policy, this is primarily in response to weaker economic growth and falling inflation, and is unlikely to result in a renewed credit boom. Indeed, if US rates begin to rise, this will likely increase the cost of capital across Asia, potentially triggering more stress among borrowers in the region.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Special Situations and Direct Lending Offer the Most Potential. As noted, we consider special situations and direct lending strategies to offer the most compelling opportunities within alternative credit in Asia today. In Asia, private equity investments have primarily been of the minority “growth capital” form rather than the majority “buyout” model dominant in developed markets. Yet given today’s low valuations, many business owners are reluctant to dilute their ownership or believe their need is temporary and are thus willing to consider alternative forms of capital under various names: private lending, private debt, structured lending, or direct lending, the term this paper will adopt. Often, the need for capital is related to a special situation, making it even more difficult for bank credit officers to price or underwrite the risk. Examples could be a need to finance a time-sensitive acquisition; a recapitalization of an ailing subsidiary of a larger business group; or temporary balance sheet issues creating the perception of poor creditworthiness, leaving a business unable to tap banks or other lenders.

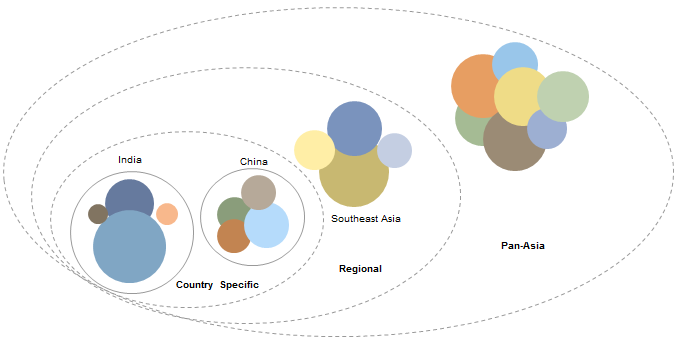

The manager landscape for the special situations and direct lending strategies offers numerous pan-Asia, Southeast Asia, and country-specific (China and India) opportunities. In Figure 6, we show our view of the institutional-quality manager landscape. Each bubble reflects an individual manager and the size of the bubble reflects the size of the fund. While some managers focus exclusively on direct lending to relatively healthy companies and others on resolving special situations, the reality is that the two strategies are intertwined, particularly in Asia. Not all direct lending involves a special situation, but most special situations require some form of direct, highly structured lending.[2]Furthermore, special situations and direct lending are distinct from strategies focusing on “structured credit” products, which involve investments in asset-backed securities, collateralized debt … Continue reading

Source: Cambridge Associates.

Note: Bubbles represent individual managers , and size of bubbles represent size of the funds.

From the investment manager’s perspective, these strategies are attractive because the manager does not have to pay up for above market equity valuations that the business owner is hoping to achieve, yet can still enjoy the returns from a growing business. Although these returns lack full equity upside, they often come with heavy downside protection. For investors, these strategies offer the potential for equity-like returns with a yield component and moderate downside protection, without being reliant on high economic growth or the equity market for exits.

For investors seeking diversification of returns beyond just equities, whether publicly traded or privately held, and also seeking the benefits of ongoing cash yield and downside protection, special situations or direct lending strategies could be attractive. These strategies are tailored for cyclical downturns, with their downside protective structures, but also work well delivering (high) yield as the credit and business cycles peak, when high-flying companies may not want to issue equity.

What About Distressed Opportunities? We have yet to reach the point where true distressed opportunities are plentiful. Even if they were, obstacles in the form of less developed or less tested regulatory frameworks on creditor rights would prevent successful execution of these strategies, at least in emerging Asian economies.

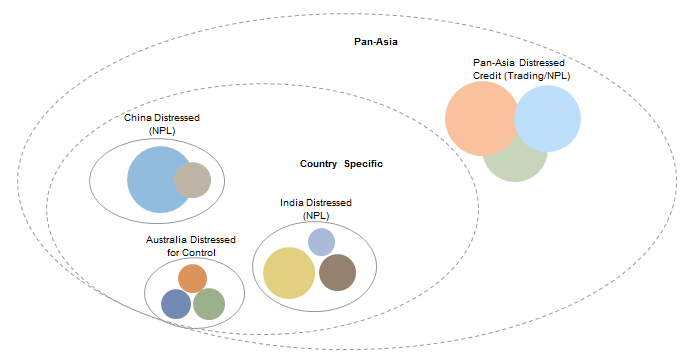

Few distressed for control managers exist in Asia (Figure 7). Of those that do, some have opportunistic investments in Japan and South Korea, but the majority of managers focus on Australia given that country’s strong legal systems and lack of cultural aversion to takeovers seen elsewhere in Asia. The bulk of the distressed opportunities are in the credit (trading and NPL) space. These managers are typically hedge fund–like groups that focus on pan-Asia strategies, mostly within the developed markets of Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea, given larger credit markets and stronger legal systems. A handful of NPL specialist managers focus on China and India. NPL disposals have been increasing in China (but are still modest in scale), while India has seen a rash of disposals recently amid a push by the new government to clean up the banking system. We see increasing interest in Indian NPL opportunities by managers, though there remains skepticism about the attractiveness of prices being paid for Chinese NPLs at the moment. In general, distressed credit opportunities are likely to grow when the credit cycle takes a turn for the worse (as it did over the late 1990s and early 2000s), but as of now the opportunity set remains limited (Figure 8).

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Note: Bubbles represent individual managers while size of bubbles represent size of the funds.

Sources: Thomson Reuters Datastream and the World Bank.

Characteristics of Special Situation/Direct Lending Strategies in Asia

As noted, special situations and direct lending are often blended in managers’ mandates, though they are distinct strategies. This section discusses characteristics based on a review of documents for several managers we are familiar with in the space.

Fund Level. Unlike private equity funds, which have a five-year investment period, ten-year life, and return targets of at least 2 times paid-in capital net of fees and expenses, special situation and direct lending funds typically have:

- Fund lives of between five and seven years, with possible fund extensions of one to two years;

- Investment periods of between two and four years;

- Targeted fund-level returns of between 1.5x and 2x for direct lending and 2x to 2.5x for special situations, heavily dependent on recycling realizations into new investments and, in the case of special situations, the employment of equity instruments or options to achieve the higher end of the range; and

- Most charge private equity–like “2 and 20” fees, with return hurdles between 8% and 10%.

In addition, there are also hedge fund–like vehicles with 90- to 180-day notice periods and investor-level redemption gates, which we believe are a poorer fit for this strategy, due to the resulting duration mismatch between the source and use of funds.

Fund sizes in recent fund-raising cycles have been between $200 million and $800 million, with pan-Asian funds at the larger end of the range. Some of the developed Asia–focused distressed managers have targeted or raised more than $1 billion. Given the smaller fund and deal sizes, these Asia-focused funds target opportunities that are generally too small for global credit or distressed players with much larger funds. This partly explains why they are able to source higher-returning deals from various borrowers.

Manager Level. For the most part, the professionals staffing special situation or direct lending managers have credit research and analysis backgrounds at corporate and investment banks. Many have also worked on special situation investing at hedge funds or the proprietary desks of investment banks—entities that in the past allowed wide leeway in investment style, permitting them to invest where regular banks could not.

Given this background, most special situation and direct lending managers have traditionally operated from financial centers such as Hong Kong and Singapore, where many of the deals are structured given rule of law and creditor’s rights (although underlying investments may be elsewhere).

Yet Asia has many disparate underlying political and regulatory regimes, so managers must possess a deep understanding of corporate law, creditor rights, and bankruptcy processes in each country where they operate. Thus, some managers focus on a single country, while pan-Asian managers typically have local capabilities and experience in each of the countries in which they are active. We would be skeptical of any manager that does not have strong local expertise, especially in emerging Asian countries.

Deal Level. The focus of special situation and direct lending investments is on securing a minimum contractual return, having adequate protection in case the borrower cannot pay up, and seeking possible return enhancement through partial equity or equity options, though the primary return driver is repayment of the loan through company cash flows. Typical deal sizes range from $10 million to $50 million in companies that generally have under $500 million in equity value, although deals with companies in the $1 billion size range are not uncommon. Other characteristics of deals (highly generalized as the details will be unique to each transaction) include:

- Tenures ranging between 12 and 36 months;

- Effective IRRs of between 15% and 25%, achieved through a combination of upfront fees and interest payments, which typically translates to between 1.3 and 1.6 times invested capital over the life of the loan;

- No leverage at the investment level (i.e., returns targets are unlevered);

- Collateral of up to several times the principal, often in the form of personal guarantees from the business owners, shares in the underlying business, its affiliates, subsidiaries, or even unrelated businesses controlled by the owners, real estate, etc.;

- Financial and operating covenants;

- Contracts agreed and enforceable in a jurisdiction with strong judicial processes, such as Hong Kong or Singapore, and often in foreign currencies such as US dollars (regardless of the location of the underlying company/investment);

- Equity options, allowing the manager to enjoy additional returns; and

- Pre-payment penalties, make-whole clauses, and other mechanisms to ensure minimum return hurdles.

Sector exposure varies, but typically companies are in industrial/cyclical sectors, which allows for physical collateral for loans. Real estate lending is also common, but depends on geography and manager preference. Geographic exposure also varies by manager and strategy. But most special situation or direct lending opportunities are in emerging Asia (China, India, Indonesia, etc.), with select opportunities in developed Asia (Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore).

Considerations and Risks

As with any investment strategy, special situation and direct lending strategies have various risks.

Default Risk. Special situation and direct lending investments are analogous to high-yield debt. Default risk is exacerbated by the potentially poor or long legal process to enforce contractual terms. Managers often need to exert significant personal influence on borrowers (moral suasion) to protect their investments, as simply exercising contractual terms through judicial processes may be difficult, slow, or impossible. Personal and business contacts are very important in this regard.

Prepayment Risk. Where the borrower is fundamentally healthier than projected or sorts out specific issues earlier than expected, it may pay debt ahead of time. While this may boost internal rates of return, it will cause cash-on-cash multiples to be low and force the manager to find an alternative investment with equivalent or higher yield at short notice. Prepayment and make-whole penalties are ways to mitigate this, but equally important is a steady pipeline of deals such that prepayments can be quickly re-invested.

Currency Risk. Investments in emerging markets entail considerable currency volatility, as investors in India and Indonesia found out in 2013. Hedging is either not possible or prohibitively expensive for these emerging Asian currencies. Managers usually try to address these risks by structuring the investment in hard currency, typically in US dollars. Where that is not possible, collateral and make-whole provisions are used to recover a minimum return in US dollars. Where such provisions are not used, currency risk must be borne, which typically leads to even higher yield expectations to justify the extra risk.

Political/Regulatory Risk. The political and regulatory frameworks in emerging economies are in constant flux. Adverse developments with strong political or socioeconomic backing can act against all investors, not just special situation or direct lending investors. This risk is arguably mitigated somewhat in special situations and direct lending compared with private equity, as judicious offshore structuring with offshore collateral helps minimize downside.

In addition to these broader risks, these strategies also have manager-related risks.

Short Track Records. While most managers operating in this space have years of experience investing in Asia, many have relatively short records in their current organizational setup, with the majority having spun out of banks or hedge funds within the last five to ten years. Detailed track records of their performance at their earlier employers is hard, if not impossible, to obtain or properly attribute.

Broad/Flexible Mandates. The special situation and direct lending space itself is relatively new and evolving. Rather than being a segment, it is a catch-all for any debt-like financing that occurs outside “traditional” debt markets, and investment theses and structuring can be very broad and opportunistic. It is not uncommon to find managers purchasing distressed debt, making direct loans, and providing special situation financing, sometimes in the same fund, and occasionally in the same deal. While this can offer portfolio diversification and allow managers to adapt to the credit cycle, it may also result in manager overreach and strategy drift.

Conclusion

Asia has both excited and disappointed private equity investors in recent years. Slowing growth, high valuations, and unpredictable IPO markets, to name a few issues, are partly to blame. Special situation and direct lending funds are a way to circumvent some of the pitfalls of private equity investing in these markets. Such funds will not deliver typical private equity returns of 2.5x to 3x returns at the fund level, but if carefully structured in the hands of a skilled manager, they can achieve a stable 1.5x to 2x with the potential for more, and in a shorter time frame. Thus, these funds can maintain private equity–like IRRs without the kind of dependence on fickle public markets and IPOs that now hobbles private equity–invested companies.

If the credit cycle fully turns and macro conditions deteriorate, the opportunity set and return potential for alternative credit in Asia will only broaden. Thus, investors do not need to have an overly positive outlook for the region to feel comfortable with such investments. By identifying skilled managers now, investors can prepare for the eventual emergence of a distressed cycle in Asia over the next few years. While many high-quality managers have already completed their most recent fund raisings, we expect managers, both existing and new, to raise additional capital over the next few years.

As with all investments there are risks, and given the complex and highly regulated nature of the opportunity set, manager selection is of utmost importance. Investors should focus on managers with clear expertise and ample resources to both source and properly structure deals.

Footnotes