Growing macro risks weigh on the outlook for Eurozone equities and lead us to a neutral view

- We moved our view on Eurozone equities to neutral in July given stalling earnings growth, unintended consequences from ultra-low interest rates, and rising political risks.

- Eurozone equities remain fairly valued and earnings growth, while disappointing, has been reasonable relative to some other markets. Together, these factors might argue for a continued overweight to the Eurozone. However, macro risks seem greater for the Eurozone than for other markets, and this suggests investors should demand a higher-than-average cushion to continue to overweight the asset class.

- We run the risk of missing a rally which correctly anticipates any subsequent de-escalation of macro stresses, but as we have seen in recent years, such rallies can prove fleeting unless fundamentals have permanently changed.

For example, see: Wade O’Brien et al., “European Equities: Time to Focus on the Micro,” Cambridge Associates European Market Commentary, October 2013; Wade O’Brien et al., “Slowly But Surely: Investors Should Stay the Course in European Equities,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, June 2014; and Wade O’Brien et al.,, “European Equities: Too Early to Take Profits,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, May 2015.

See the third quarter 2016 edition of VantagePoint (a quarterly publication from Cambridge Associates’ Chief Investment Strategist), published July 11, 2016.

We have been constructive about European equities for almost three years, believing that a combination of attractive valuations, improving earnings prospects, and a stabilizing macro backdrop would help generate attractive returns. During this time, macro challenges have ebbed and flowed and the European Central Bank (ECB) has supported growth with extraordinarily dovish monetary policy, while company fundamentals slowly recovered and a minor rebound in earnings took place. Along the way, we pivoted from a Europe-wide overweight to a more focused Eurozone recommendation, attracted by tailwinds such as the weakening euro and a rebound in demand for credit. In July, we shifted our view on Eurozone equities back to neutral given stalling earnings growth, unintended consequences from ultra-low interest rates, and rising political risks.

In this note we review the state of Eurozone equities today, looking at the macro picture, earnings, and valuations. Though valuations for Eurozone equities remain attractive, waning earnings growth and the difficult macro picture keep us neutral for now, but continuing to watch closely as US valuations push ever higher.

Macro Conditions Have Improved, But Not to Extent Desired

Eurozone economic conditions have improved in recent years, though probably not to the extent desired by policymakers or anticipated by financial markets. After the region slowly emerged from recession at the end of 2013, GDP growth reached 1.5% in 2015. Economic growth in 2016 is expected to be similar, though downside risks are growing. The ECB has helped underpin growth through several mechanisms, including cutting its base rate to negative territory and expanding its asset purchases (both in terms of volume and asset types). Lower borrowing costs in turn have boosted spending capacity for sovereigns and consumers, with a growing populist backlash against austerity also putting pressure on governments to loosen the purse strings. Fears over excessive sovereign debt levels have, at least for the time being, moved to the backburner. Unfortunately, statistics from countries like Greece, where debt/GDP still stands around 175% despite several consecutive bailouts, underscore that the situation has not been resolved.

For more on this, please see Eric Winig, “Brexit: Outlier or Harbinger,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, July 20, 2016.

Despite this gradual economic improvement (or perhaps because of it), efforts toward structural reforms have disappointed, notwithstanding progress in select countries in labor reforms and bankruptcy procedures. Political risks are rising given growing disquiet over immigration and lackluster growth in many countries. Voters in the United Kingdom shocked markets in June by voting to leave the European Union. How exactly this “Brexit” will play out is uncertain (and seems unlikely to occur before 2018, at the earliest); what is clearer is that the resulting uncertainty over trade policy and regulations is likely to curb investment and activity for some time. Even more worryingly, similar anti-EU sentiment is growing on the Continent. The next milestone will be the Italian constitutional referendum on which current Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has staked his leadership. Should the referendum scheduled for the fourth quarter fail and Renzi resign, a more populist party could come to power, and possibly lead to an opportunity for Italians to vote on leaving the EU. Next year only brings further possible flashpoints, including national elections in France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Pro-EU parties hold majorities in these countries for now, but clearly the risks of a market-unfriendly event and possibly even Eurozone breakup are rising.[3]

Equity markets seem to have anticipated the 2014–15 economic rebound and easing concerns over sovereign debt levels, as Eurozone stocks rose nearly 40% between mid-2013 and mid-2015 before their cyclical performance peaked (Figure 1).[1]Technically, performance peaked in March 2015 but by July Eurozone stocks had again come within 1% of that peak. This performance easily surpassed that of developed markets peers, though still left investors nursing underperformance from earlier in the decade. Despite this run-up, the ten-year annualized return for Eurozone stocks today stands at just 1.7%—slightly below their dividend yield.

Figure 1. Eurozone and Developed Markets Equity Performance Over the Past Three Years

August 31, 2013 – August 31, 2016 • Local Currency • August 31, 2013 = 100

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: World represented by the MSCI World Index and Eurozone by the MSCI EMU Index. Total returns for MSCI developed markets indexes are net of dividend taxes.

Reinforcing the old adage that waiting for the macro data to confirm the rebound means investors miss a large share of the rally, investors that waited until last spring to buy into the Eurozone recovery have been left nursing losses. Eurozone stocks have returned -1.9% over the past 12 months (through August 31), significantly underperforming developed world peers (6.4%). Financials (-18.7%) generated most of this loss but had many partners in crime; health care (-10.6%), and telecom stocks (-10.8%) also posted large losses.

How Much Have Earnings Driven Underperformance?

Eurozone equity performance has tapered off for a variety of reasons including overly optimistic earnings forecasts, rising political risks, and growing unease over extreme monetary policy. Attractive valuations, at least thus far, have not been enough to offset these sentiments, though as explained later, some of market’s concern about Eurozone equities seems misdirected.

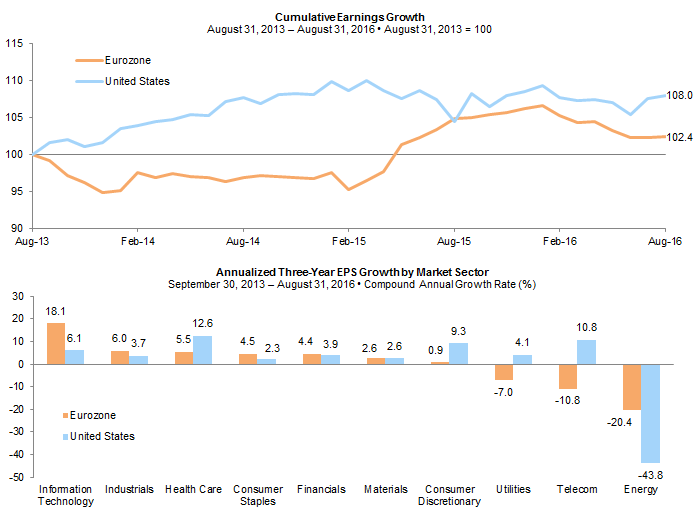

Eurozone earnings growth has been disappointing on an absolute basis. Index earnings have barely budged over the past three years (Figure 2). Contrary to popular perception, financial sector earnings growth over the same period (+14% cumulatively) has actually boosted index earnings, while sectors such as energy (-50%) and telecoms (-29%) have been significant drags. More recently index earnings have softened[2]Through August 31, trailing earnings have declined around 2% over the past 12 months. and the financial sector has been a drag (sector earnings have fallen 6% over the past 12 months). Still, there has been plenty of blame to spread around given declines for sectors like energy (-27%) and the lack of support from staples (flat) and discretionary (-1%).

Sources: I/B/E/S, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Eurozone represented by the MSCI EMU Index and United States represented by the MSCI US Index. Analysis based on the trailing 12-month earnings per share.

While acknowledging that Eurozone earnings growth has been lackluster, this would seem an insufficient basis for underperformance given similarly weak earnings growth for US and other developed markets equities. Over the past 12 months US stocks have outperformed Eurozone equivalents by over 1,300 basis points (bps) despite flat-lining earnings.

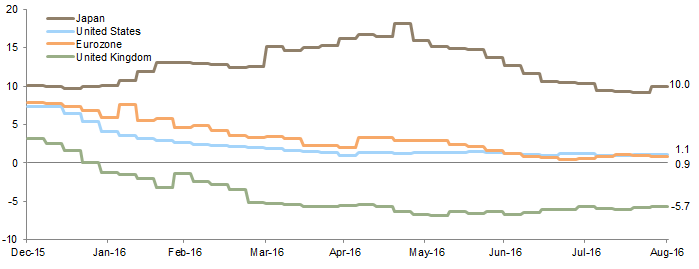

One explanation is that markets are forward as opposed to backward looking, and Eurozone earnings seem to be trending downward. Earnings expectations for the Eurozone have come down, mirroring trends in other major markets. Eurozone companies are now expected to grow earnings just 1% in 2016, down from around 8% at the start of the year (Figure 3). For comparison, expected US earnings growth has fallen from 7% to around the same level. Markets may have been expecting US disappointment or looking forward to 2017, but clearly the bar was set higher for the Eurozone.

Figure 3. Consensus Earnings Growth Estimates for Fiscal Year 2016

December 31, 2015 – August 31, 2016 • Percent (%)

Sources: I/B/E/S, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Data are daily. Japan represented by the MSCI Japan Index, United States by the MSCI US Index, Eurozone by the MSCI EMU Index, and United Kingdom by the MSCI UK Index. Fiscal year 2016 for Japan ends March 31, 2017.

The lack of earnings growth in the Eurozone is disappointing given that higher operating leverage was expected to kick in as economic conditions improved. One thesis supporting our view to overweight Eurozone equities was that higher sales growth would boost margins and thus profits, but this has not been confirmed by recent results. Not only have earnings barely budged, but revenues have actually contracted and progress has been uneven across sectors, with some experiencing negative operating leverage. For example, over the past three years consumer discretionary sales have grown by a cumulative 24%, but sector earnings are only up 3%. The flipside of this weak performance is that Eurozone companies may retain more capacity to cut costs and boost margins than peers in markets like the United States (where margins are shrinking given tighter labor markets), but it is disconcerting that operating leverage has thus far failed to materialize.

Stronger domestic economic growth may have failed to generate a sufficient lift for index revenues or profits for several reasons. Inflation has been non-existent, which constrains the ability of companies to raise prices and generate operating leverage. Weaker global conditions may also have served as a countervailing force as Eurozone companies are highly reliant on foreign sales—global GDP growth was just 3.1% last year, well below its 3.8% post-2005 average (Figure 4). Together, Eurozone companies derive almost 50% of their sales from abroad according to Deutsche Bank, with the share well above 50% for sectors like health care and consumer staples. The slowdown in emerging markets (which account for around 20% of overall sales) has been especially painful, and weakness in many emerging markets currencies may have served to offset some of the benefit to earnings of the rising dollar (the United States is around 18% of sales). A rebound in global growth could bring significant gains for European companies, though prospects for this seem to be dimming as fourth quarter 2016 approaches.

Source: International Monetary Fund – World Economic Outlook Database.

Note: GDP figures for 2016 and 2017 are estimates.

The wide range of geographies in which Eurozone companies conduct business may help explain why a weaker euro hasn’t translated into significantly higher corporate profits (Figure 5). Sector effects distort some of the data, as weaker earnings for financials, telecommunications, and utilities (domestically focused sectors) may disguise some of the benefits to exporters from the cheaper exchange rate. Sectors that are highly reliant on foreign sales (including health care and industrials) have seen among the highest earnings growth. Still, some of the benefits from currency depreciation may be offset for companies that incur revenue and costs abroad, limiting their upside from currency depreciation. The ECB’s ability to further depress the undervalued euro is also increasingly being called into question, and another bout of global macro instability could mean the currency’s safe-haven status causes it to appreciate.

Sources: European Central Bank, I/B/E/S, MSCI Inc., Thomson Reuters Datastream, and WM/Reuters. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Eurozone is represented by MSCI EMU Index. Trade-Weighted Euro is represented by the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro, as calculated by the European Central Bank.

Valuations Are Still Reasonable

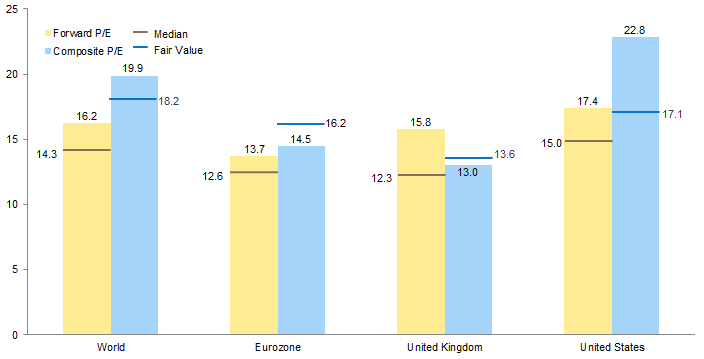

Valuations for Eurozone equities have “round-tripped” over the past three years, rising in conjunction with underlying share prices before cresting in March 2015. Today Eurozone stocks appear fairly valued, trading at 14.5 times normalized composite earnings (Figure 6), a 10% discount to their historical median, and roughly where were during the fall of 2013. Short-term metrics suggest shares are more fully valued; the trailing price-earnings ratio of 19.3 is about 10% above its historical median.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: World represented by the MSCI World Index, Eurozone by the MSCI EMU Index, United Kingdom by the MSCI UK Index, and United States by the MSCI US Index. The composite normalized price-earnings (P/E) ratio is calculated by dividing the inflation-adjusted index price by the simple average of three normalized earnings metrics: ten-year average real earnings (i.e., Shiller earnings), trend-line earnings, and return on equity–adjusted earnings. Median for forward P/Es based on data from June 2003 to present. CPI data are through July 31, 2016.

For more on this, please see Wade O’Brien et al., “Opportunities Arising from Banking Sector Stress in Europe,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, August 24, 2016.

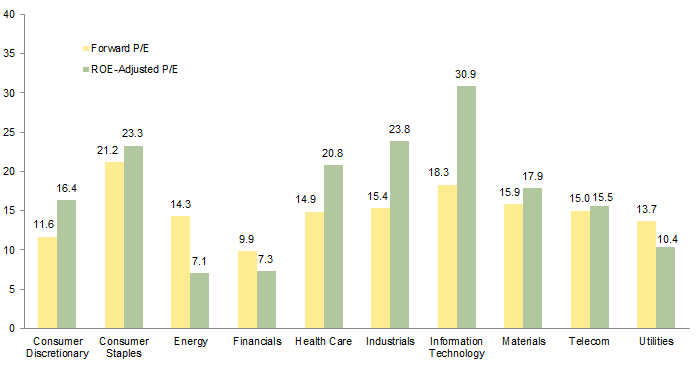

Data on sector valuations suggest the discount on offer in Eurozone equities is not confined to one particular sector. Earnings weakness has pushed energy and utilities to sizable discounts relative to their historical medians, and financials have been punished by concerns over headwinds like rising capital requirements and negative interest rates. An open question exists as to whether normalized valuations exaggerate the cheapness of some of these sectors, and short-term metrics for some look less attractive (Figure 7). Putting aside the questions over the business models of many banks, energy sector earnings are also likely to be plagued for some time by write-offs relating to previous investments unless energy prices can reverse much of their recent weakness.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Eurozone represented by the MSCI EMU Index. Return on equity is calculated by dividing the index’s price-to–book ratio by its price-earnings ratio.

Relative to developed markets peers, Eurozone equities trade at a reasonable 27% discount (Figure 8). While not quite the bargain they were at the depths of the sovereign debt crisis in early 2012 (when they traded at a 32% discount), this discount is well above its 18% historical average. The current discount to US equivalents (36%) is near a historical peak. The caveat, of course, is that many developed world peers feature inflated valuations. US stocks, for example, trade around 35% rich to their historical median, and provide a benchmark that flatters other asset classes.

Figure 8. Relative Composite Normalized P/E Ratios for the Eurozone

April 30, 1998 – August 31, 2016 • Percent (%)

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Eurozone represented by the MSCI EMU Index, United States by the MSCI US Index, and World by the MSCI World Index. The composite normalized price-earnings (P/E) ratio is calculated by dividing the inflation-adjusted index price by the simple average of three normalized earnings metrics: ten-year average real earnings (i.e., Shiller earnings), trend-line earnings, and return on equity–adjusted earnings. All data are monthly. CPI data are through July 31, 2016.

The Great Unknowns

Thus far, we have established that Eurozone earnings growth has disappointed but has been reasonable relative to some other markets, the macro has improved but not to the extent desired, and valuations remain reasonable. Together, these factors might argue for a continued overweight to the Eurozone. However, macro risks seem greater for the Eurozone than for other markets, and this suggests investors should demand a higher-than-average cushion to continue to overweight the asset class.

Rising political uncertainty in the Eurozone is the largest macro risk, and one that seems more dangerous for investors than was the case two or three years ago. While the sovereign debt crisis at its depths threatened the future of the European project, the pain of a small player like Greece leaving might have been offset by greater cohesion among the remaining group. At an extreme, some even argued that economic suffering in a country that exited the EU or currency union could serve as a reminder to remaining members about benefits of membership. Unfortunately, the Brexit referendum is a stark reminder that voter belief in the benefits of EU membership has faded in recent years. Polls show many voters blame EU rules and regulations for their anemic economic growth, and rising immigration has reminded some voters of their own fragile economic security. The upcoming elections may be used by voters as a referendum to express their displeasure toward the status quo, and could lead to more countries holding votes on remaining in the EU (Figure 9). The Italian referendum (which is not a vote on leadership but rather constitutional reforms and making parliament more efficient) will be the first test later this year, but general elections in many of the larger EU nations in 2017 also could unnerve markets.

Sources: Barclays and Ipsos Mori.

The ECB’s extraordinarily loose monetary policy also is increasing macro risk for the Eurozone. The ECB is currently buying around €80 billion of assets each month, and in doing so has pushed yields on sovereign and corporate bonds to historically low levels. This has brought some benefits such as lower debt servicing costs, but payback is being seen via higher savings rates, which limit spending (it takes more assets to generate the same amount of retirement incomes), and weak projected earnings for financial institutions. With ten-year sovereign bonds yielding near zero in many countries, the traditional business of borrowing short and lending (or investing) long has become less lucrative. Asset bubbles (or at the very least distortions) are occurring in some property markets, potentially sowing the seeds for future crises. To cite one example, German house prices have risen nearly 6% per annum for the past half-decade, faster than even the United Kingdom’s. Policymakers may recognize these risks and may even eventually turn their collective efforts from monetary to fiscal easing, but signals thus far are not encouraging. Note that Germany actually has run a fiscal surplus during the first half of 2016, but continues to resist both domestic and neighbor’s efforts to loosen the purse strings.

The currency is a wildcard, though its importance should not be overstated. Figure 5 suggests there is a limited relationship between index profits and the direction of the currency. This said, some industries (chiefly those with higher foreign revenues and few offshore costs) have benefitted from the weaker euro and would likely suffer if it reversed its recent descent. The ECB (and voters) are increasingly concerned about the side-effects we’ve discussed, and any number of events might cause the currency to bounce back. One possibility is that weaker US growth causes the US Federal Reserve to slow its expected rate hikes, which despite better US data have frequently been delayed by the anemic pace of global growth.

Another significant unknown is the health of emerging markets. Eurozone companies have benefitted as data for emerging markets have improved and demand for their exports has rebounded. Emerging countries are again growing at a faster rate than developed equivalents, in part because commodity prices have stabilized and fiscal stimulus has been employed in countries like China. Should this continue, there is upside for sectors like consumer staples that receive a high share of sales form the region. However, the surge in Chinese stimulus is already fading, and the consensus expectation is that growth will continue to cool over the remainder of 2016. Emerging markets have also gotten a reprieve from the Fed’s delay in hiking rates, which has allowed central banks to keep interest rates low and boost activity through higher borrowing. Should the Fed pick up the pace and emerging markets peers follow suit, this will again challenge local growth.

Conclusion

With the benefit of hindsight, investors could have sold Eurozone equities in the spring of 2015 and locked in outperformance for tactical positions initiated in the years earlier. However, timing these decisions is difficult, and the improving macro and fundamental story seemed to support a continued overweight. Unfortunately, earnings growth seems to have rolled over, and the lack of operating leverage to this economic growth is disconcerting, as is the growing payback from low rates and structural headwinds for sectors like financials. Eurozone earnings have not been materially weaker than that seen in other markets, but the direction in which they are headed is concerning.

The even larger worry is politics. Markets seem to have quickly gotten back up and dusted themselves off after the Brexit vote, but we fear it is only a matter of time before an even more significant event (in Italy, France, or elsewhere …) roils asset prices and causes economic activity to contract. Valuations would provide some cushion were this to occur, and overvalued markets like the United States don’t look much more attractive. Still, we no longer see strong support for an overweight position to this market relative to US equities, and have moved our view on Eurozone equities to neutral. We run the risk of missing a rally anticipating any macro improvement that materializes, but as we have seen in recent years, such rallies can prove fleeting unless fundamentals have permanently changed.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Joseph Comras, Investment Associate

Footnotes