European banks aren’t going through a stormy phase that will eventually clear and permit them to claim a new golden age. The industry is undergoing a metamorphosis that will demand a thorough and radical alteration of its core operating model.

—Edward Robinson, “The Never-Ending Story: Europe’s Banking Nightmare Isn’t Over Yet,” Bloomberg News, February 16, 2016

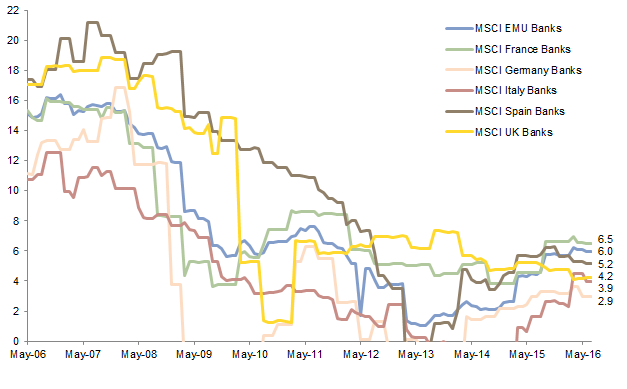

The European banking sector has been buffeted by a number of cross-currents in recent years. Regulatory changes, debt crises, and the extraordinary monetary policy deployed by central banks have boosted some activities but threatened others. Every time one threat fades away (“Grexit,” etc.), another one arises (negative interest rates impacting margins, higher capital requirements, etc.). Investors seem to have thrown in the towel: shares of European banks have plunged by more than 18% since the start of 2016, continuing their longer-running underperformance versus broader benchmarks. While valuations appear attractive, the dislocation facing the sector means it is unclear when profits will strongly rebound and allow these institutions to close this performance gap. However, the vacuum being created by banks withdrawing from previous activities is opening up opportunities for strategies like non-performing loan (NPL) funds focused on the region.

Recent Returns Have Been Dreadful

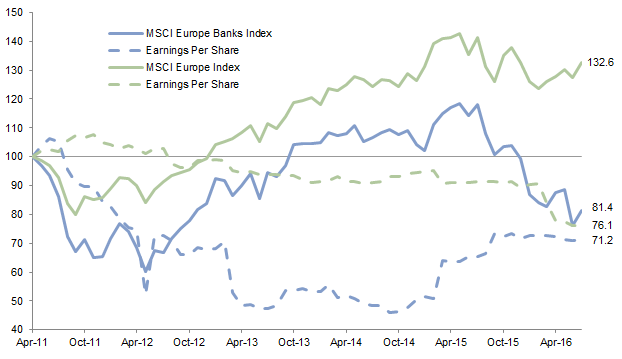

Returns on European bank stocks had already been lagging those of other sectors before taking another leg lower in June following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Though July’s substantial post-“Brexit” relief rally helped narrow their overall underperformance, European banks stocks had still returned -18% year-to-date through July 31 and -31% over the past 12 months, trailing the return of the broader index by around 2,500 basis points (bps).

Disappointing earnings announcements and guidance have come into play. Earnings have plunged 33% since June 2011, and whereas the consensus once expected around a 10% increase in sector earnings in 2016, it now expects a contraction. Despite a slowly improving macro backdrop and rising loan demand, low interest rates and flat yield curves are dampening profitability. Brexit is expected to spur additional monetary easing, further undermining loan margins for banks. Investment banks also seem to continue to struggle with their own issues, including ongoing legal issues and increasing regulatory constraints around activities like proprietary trading and lending to speculative companies. Low valuations have not been enough to entice investors to stay, given concerns also linger about asset quality; Eurozone banks now trade around 0.6 times book value, a 45% discount to their median since 1980.

Performance and EPS for MSCI Europe Banks vs MSCI Europe

April 30, 2011 – July 31, 2016 • Rebased to 100 on April 30, 2011

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Note: Data are monthly.

Outlook for Earnings

For more on this, please see Wade O’Brien et al., “Feeling Negative About Sub-Zero Interest Rates,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, March 25, 2016.

Economic growth is slowly rebounding in Europe, encouraging demand for loans from companies and households. However, one driver of this growth is rate cuts and asset purchases from the European Central Bank (ECB), which counteract the benefit for banks by pushing net interest margins lower. Typically, as interest rates on assets (loans) fall, banks would try to protect net interest margins by lowering the interest paid on liabilities (deposits). Yet with rates on deposits already near zero, they can’t fall much further. Flatter yield curves also discourage traditional carry trades that involve borrowing short and lending long, explaining in part the reduced profitability of investment banking operations. To offset these forces banks are attempting to raise fees on ATM transactions and checking accounts, as well as cut costs and grow areas like asset management, but there are limits to these efforts.

For more on SIFIs, please see the May 2016 edition of Cambridge Associates’ “Quarterly Regulatory Update.”

Proposed regulatory and accounting changes also threaten profits. Under Basel II banks were required to hold the equivalent of 4% of risk-weighted assets in higher-quality “tier 1” capital (with only half of this in core shareholder equity tier 1), but Basel III could triple or quadruple the amount of required core tier 1 capital.[1]Capital requirements will be locally implemented and vary across countries; the largest or so-called SIFIs (systemically important financial institutions) will see the largest increases. Risk weightings (dictating how much capital needs to be held) for the lowest-rated loans will also increase, reducing their attractiveness for lenders. An encumbrance ratio (limiting how much of a bank’s balance sheet can be set aside for secured funding) may constrain the ability of banks to make certain types of loans or even force asset sales. The accounting standard for recognizing NPLs is also being tightened, forcing banks to set aside reserves for potential future losses. While all such studies are theoretical and proposed standards are often tweaked before implementation, a study by KPMG focused on Dutch banks concluded that cumulatively these changes may shave as much as 5.8 percentage points off their return on equity.[2]KPMG Advisory N.V., “The State of Dutch Banks in 2015: Adjusting to the New Reality,” July 2015.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Data are monthly. Y-axis minimum set to zero to exclude periods with negative values for return on equity.

Finally, excess competition is a long-standing problem that helps constrain profitability, but in practice, the specific impact on profits from the number and types of banks operating in a country is hard to disentangle from other forces. The German banking landscape is fiercely competitive, with over 1,800 banks in operation and the top five controlling a relatively low 30% of total assets. This has impacted the sector’s roughly 3% return on equity, but so too have legal missteps and regulatory headwinds for certain institutions. Market concentration does seem to support margins in the Netherlands, where the top five banks control around 80% of assets and boast a return on equity of around 8%. Still, many European institutions operate across borders and other factors come into play. The bigger issue for some smaller banks is likely the convoluted nexus of local politicians, employees, and customers that influences business strategy, creating obstacles to efficiency drives and efforts at consolidation.

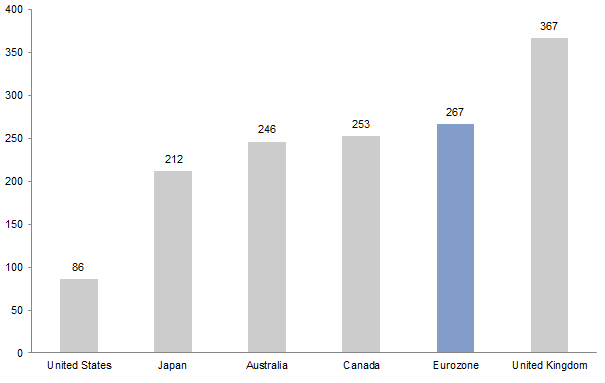

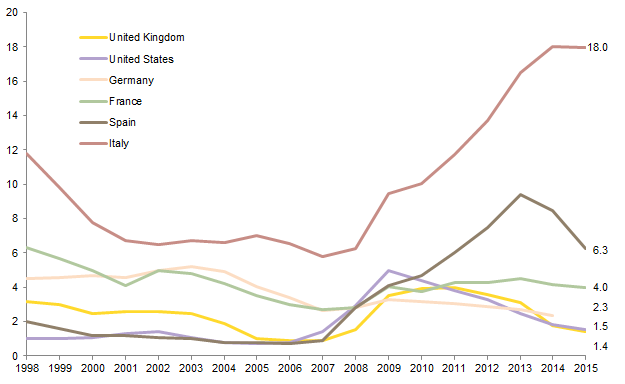

Balance Sheets Remain Large But Appear Healthier

The news on European bank balance sheets is more encouraging, and the recent stress tests of the largest banks should further placate investor fears about capital levels and loan quality. The weighted average core equity tier 1 ratio for the 50 largest European banks was 13.2% at the end of 2015, more than 400 bps higher than it was in 2011. More than €200 billion in capital has been raised by these banks in recent years (in part through retained earnings), while overall Eurozone system assets have declined by more than €4 trillion since 2008. Critics counter that European balance sheets still appear bloated relative to peers, but market structures explain some of these size differentials. European banks tend to retain home loans while US peers originate mortgages but then often sell them on to investors via asset-backed securities.[3]Rather than securitization, many European banks use an on balance sheet substitute called covered bonds. Overall, 6% of bank assets were considered nonperforming at the end of 2015[4]The European Banking Authority (using a more stringent standard) puts this at around 7%.; loan quality is improving in the largest economies but recent regulatory changes have revealed the scale of the problem in countries like Italy.

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Eurostat, Japan Cabinet Office, Office for National Statistics – UK, Reserve Bank of Australia, Statistics Canada, US Bureau of Economic Analysis, and US Federal Reserve.

Notes: US bank asset data represent both domestically chartered and foreign-related commercial banking institutions. Foreign-related institutions include US branches and agencies of foreign banks as well as Edge Act and agreement corporations. According to some estimates, using International Financial Reporting Standards-equivalent accounting would increase the amount of US bank assets to GDP by around 30 percentage points. Japan bank asset data represent domestically licensed banks and foreign banks operating in Japan. Domestically licensed banks include banking accounts, trust accounts, overseas branch accounts, and city banks. Australia bank asset data represent the assets of authorized deposit taking institutions (ADIs) in Australia. ADIs include banks, building societies, and credit unions. Canada bank asset data represent the total Canadian dollar and foreign currency assets of Canadian chartered banks. Eurozone bank asset data represent assets of domestic banking groups and stand-alone banks and foreign (EU and non-EU) controlled subsidiaries and foreign (EU and non-EU) controlled branches, irrespective of their accounting/supervisory reporting framework. UK bank asset data represent total sterling and foreign currency (including euro) denominated assets of monetary financial institutions (excluding the central bank).

Source: World Bank.

Notes: Data represent latest available as of August 10, 2016. German data for 2015 are not yet available. Data are annual. Bank non-performing loans to total gross loans are the value of non-performing loans divided by the total value of the loan portfolio (including non-performing loans before the deduction of specific loan-loss provisions).

The Real Opportunity May Not Be in Bank Equities

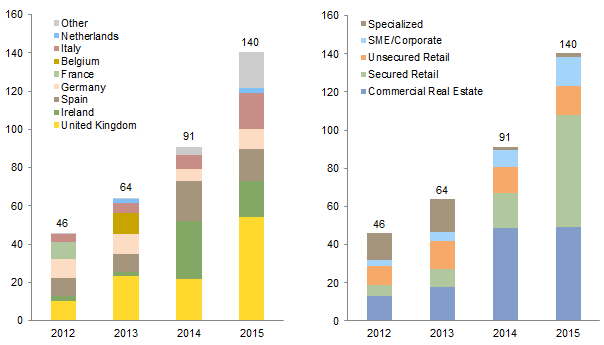

Investors like private equity firms and hedge funds are seeing a number of opportunities arise from the dislocation affecting the financial sector and regulatory changes. European banks still hold around €1 trillion in NPLs, and a similar amount of assets designated as non-core. Higher capital requirements and more stringent oversight are encouraging banks to shed NPLs, while accounting changes and shareholder pressure are also encouraging banks to sell non-core assets and conduct more focused operations. European banks and national bank resolution funds (so-called bad banks) sold around €140 billion of assets in 2015, a 54% increase from the year before, with the United Kingdom, Italy, and Ireland among the most active markets. While the scope for further disposals from certain markets is fading (Ireland’s National Asset Management Authority is down to around €10 billion in assets and the United Kingdom’s Asset Resolution Authority is down to around £43 billion), new opportunities are arising. Deloitte & Touche has suggested that loan sales could hit €130 billion in 2016, with NPL sales increasing in countries like Italy and non-core sales picking up in the United Kingdom.

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Notes: Country is based on the location of the respective bank’s head office. Specialized sector includes structured and asset-backed products, shipping, infrastructure, energy, and aviation.

Specific countries are encouraging banks to sell NPLs in different ways. Countries like Greece have passed legislation that allows NPLs to be sold to non-bank entities for the first time, while others like Italy have changed tax laws to accelerate the schedule over which banks could deduct losses on NPLs from taxable earnings. Changes in local bankruptcy laws that accelerate the process or allow debt restructuring prior to bankruptcy being declared have facilitated this process, as the faster a private equity firm can work out a distressed loan, the higher its rate of return. State-backed resolution authorities sell but also buy distressed assets, boosting liquidity and thus forcing banks to more accurately mark to market, in turn also encouraging sales.

Distressed debt and other private equity funds have harvested these opportunities successfully in recent years, and may see even richer opportunity if loan sales accelerate. These funds often benefit from their size (many vehicles exceed €1 billion), as sellers such as bad loan banks often want to sell large blocks of loans and only a small number of institutions can write checks of €100 million or more. Some of the distressed funds have purchased loan servicers in different countries, offering deeper insight into loan quality and local bankruptcy practices. Potential limited partners evaluating this opportunity should consider the access of the general partner to assets, especially given how concentrated the NPL market is in some jurisdictions. The most successful funds will also need discipline to avoid overpaying for assets as competition heats up and the quality of loan sales improves in some markets.

Direct lending funds (which require investors to lock up capital for a multi-year period) are also seeing growing opportunities. European companies are more reliant on loans from local banks than equivalents in other countries that rely on capital markets: around 85% of European company external financing comes from bank loans, in part due to the smaller average size of European companies. Banks in which governments hold large stakes (such as in the United Kingdom) are being encouraged to trim loan books and narrow their focus, and more nimble entrants are looking to fill this void. Capital constrained banks in some countries lack the capacity to participate in new loans, also opening markets to new players. Some of these direct lending funds will post attractive risk-adjusted returns, but manager selection will be important. Falling yields on loans create a headwind to returns, and care will be required to avoid credit deterioration (NPL ratios for European small- and medium-sized enterprise loans are currently around 18%). The growing number of firms raising money to target this opportunity also suggests caution, as the industry has gone from virtually nothing to €50 billion in the span of just a few years. Historically, skilled managers have been able to limit loan defaults by careful underwriting; targeting markets where economic growth has been healthier is also important. These lenders can also typically execute more quickly for time-pressed borrowers, offering an advantage; the reduction in competition from banks in some areas may also help protect margins given the growing interest from other private equity firms in the space.

The Bottom Line

European financials face many headwinds, including increasing capital requirements and pressure on net interest margins from low interest rates. The slowly improving macro environment will be insufficient to offset these forces. Publicly traded banks have also faced idiosyncratic issues like weak trading revenues and/or poor cost control. As we are unsure when these clouds will lift, we are not tempted to increase exposure to the sector despite attractive valuations. However, the dislocation impacting the industry is creating other opportunities. Private equity firms and hedge funds are stepping in and buying unwanted assets, as well as making loans in markets that large banks are pulling away from. Depending on their risk tolerance and ability to lock up capital, investors with the ability should take a close look at these funds, as some are likely to generate attractive returns in the years ahead.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Stuart Brown, Investment Associate

Footnotes