As entrepreneurs know well, the process of creating and managing a successful business is complex and requires great skill, insight, and hard work. Successful management of significant wealth requires similar attributes; however, not all the characteristics fundamental to entrepreneurial success translate to effective portfolio management.

This can create challenges for entrepreneurs—whether they are still actively running their company or have stepped away from day-to-day oversight—as they begin to focus more on how to invest their hard-earned capital. Although each owner’s perspectives and input are essential to the ongoing stewardship and growth of their wealth, the instincts that have driven their success as an entrepreneur may not always serve them as well when it comes to wealth management.

This paper presents five recommendations for those looking to build an investment framework that can be as successful and personally rewarding as building a business.

1. Reset Your Method—and Measure—of Success

Many of the most successful owners have become so by adhering to some core business principles, including:

- Prioritizing short timeframes,

- Divesting from underperformers, and

- Anchoring to absolute performance metrics.

Yet these principles, when applied too absolutely to investment strategy, can be detrimental to a portfolio’s long-term performance. Business owners looking to successfully manage their capital may be better served by redefining their time horizon, how they allocate capital, and how they measure success.

Let Time Be on Your Side

In many ways, entrepreneurs are the definition of long-term investors. After all, many have spent their lifetimes patiently and tirelessly building their businesses. Yet time also can be their enemy. Whether due to the competitive value of being a first mover or the need to satisfy shareholders’ quarterly expectations, time can be an unaffordable luxury.

Investment management, however, generally requires a relatively long period before results are achieved. A short-term focus can mean losing out on value that accrues over time or undercutting gains due to the significant tax costs associated with rapid portfolio turnover. Decisions based on short-term—and, thus, possibly incomplete or misleading—data also can lead to significant capital loss or compromised returns.

In its 2021 Quantitative Investor Behavior Study, DALBAR evaluated mutual fund investors’ actual realized returns, as opposed to reported results. For the 20-year period ended December 31, 2020, the average equity index fund investor experienced only a 6.0% annualized return versus 8.3% for the comparable global equity index, due to not remaining invested for the full period. An investor allocating $1 million consequently would have achieved $1.7 million less than the fund’s reported results. Although average retail fund investors and wealthy investors differ in many ways, this study highlights a behavioral risk that is universal and should be accounted for in any portfolio strategy.

Don’t Discount the Underdogs

Understandably, an entrepreneur’s instinct often is to invest in what is working best. After all, building a successful business requires allocating resources to top-performing divisions or products and sometimes making difficult choices about underperformers.

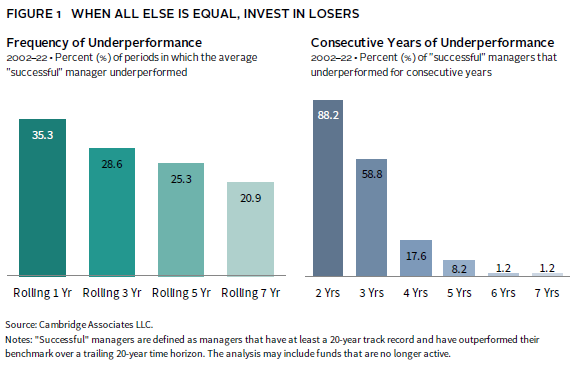

Over the lifespan of a portfolio, however, virtually all investments underperform at some point. Figure 1 looks at successful managers over the last 20 years, defined as global equity fund managers that outperformed the benchmark and remained in business. The first chart depicts how often this group underperformed relative to the index. On average, “successful” managers underperformed about one quarter of the time over any rolling three- and five-year periods. Of these same successful managers, as shown in the second chart, more than 88% underperformed for two years in a row, and more than 58% underperformed for three consecutive years.

Only deploying capital into clear winners and/or avoiding underperformers entirely is likely a recipe for failure, given investment performance cycles. Similar to business acquisitions, the best time to buy a fundamentally sound enterprise is when temporary underperformance or market dynamics have driven its price down. Short-term underperformance can represent a window of opportunity for the wise investor who works to identify true long-term outperformers.

Rethink What Great Means

Successful business owners are often stars in their fields. Their businesses grew and amassed capital, turning performance goals into achievements, and achievements into future expectations. However, expecting such remarkable success in investing is likely to cause disappointment. It may also signal that the investor is evaluating success in a way that could take their capital management strategy off course and create greater long-term risk.

In transitioning from running a business to growing a diversified portfolio, entrepreneurs should adopt a nuanced definition of success. Specifically, portfolio strategy—including individual asset allocation and investment decisions—should be driven by the objectives and risk tolerance of the investor. Each investment’s purpose in serving the investor’s goals should determine its fit and weight within the larger strategy. For instance, these goals can include minimizing volatility, providing inflation protection, achieving tax efficiency, defending against capital loss, or reflecting a strong belief in social or environmental sustainability. This is not to suggest that business owners should lower their standards, but rather that they should consider the role each investment can play in a portfolio beyond outperformance in every period.

For those accustomed to meticulous management of corporate balance sheets, the natural inclination to painstakingly analyze the performance of each individual line item can be hard to resist. But focusing on aggregate results can provide a clearer total investment picture, prevent counterproductive detours, and help ensure a steady path to success.

2. Complement Your Concentration

Entrepreneurs often earn their success by focusing a considerable amount of time, money, and other resources on one thing: building their business. As a result, many hold a significant concentration of wealth in a single investment, a situation that can persist even in cases where the owner has transitioned away from day-to-day management.

For more on this topic, please see Doug Macauley and Nicole Nava, “Business Ownership at a Crossroads: Key Questions for Planning What’s Next,” Cambridge Associates LLC, March 18, 2022.

Although concentration can lead to wealth creation, it also can destroy wealth. Businesses are subject to idiosyncratic risks that can result in failure or simply underperformance. For example, 50% of S&P 500 constituents underperformed the S&P 500 index in the 20-year period ending in 2021. While this is an acceptable or necessary risk for many entrepreneurs, concentrations should still be regularly evaluated to ensure they remain appropriate for an individual and his or her family.

Specialization, and its attendant risks, is a way of life for some business owners. In such cases, holding a large portion of wealth in a business can serve as a hub around which a complementary portfolio can be constructed. Consider the case of a pharmaceutical entrepreneur who founded a now multi-$100 billion public enterprise and consequently amassed considerable wealth in the stock. This entrepreneur remains actively involved in the company and its continued success. Although the entrepreneur believes in its long-term growth prospects, the stock has significant price volatility, and the entrepreneur has liquidity needs that could be better served by more stable assets. As a solution, a portfolio of diversifying strategies (e.g., multi-strategy hedge funds, global macro, systematic/trend, and specialized credit) with near-zero or negative correlation with equity markets is constructed. This provides an important portfolio ballast, complementing the entrepreneur’s concentrated growth engine while serving as a reliable source of liquidity and defense during equity declines.

Ultimately, the right level of concentration and the appropriate asset allocation strategy overall is unique to each investor. What is the investor’s time horizon? What types of risk do they want to take on? What are their other holdings? What is the vision for the portfolio and how should it complement the investor’s business holdings? These and many other questions help provide the context needed to form the appropriate investment response.

3. Use Your Scale and Background to Your Advantage

Having built their business, often from the ground up, business owners sometimes have distinct competitive advantages as investors. The scale of their investable capital and specialized industry knowledge can be put to good use in the investment world.

Explore the Possibilities of Private Investing

See Maureen Austin, David Thurston, and William Prout, “Building Winning Portfolios Through Private Investments,” Cambridge Associates LLC, August 5, 2021, and Maureen Austin and David Thurston, “Venture Capital Positively Disrupts Intergenerational Investing,” Cambridge Associates LLC, January 13, 2020.

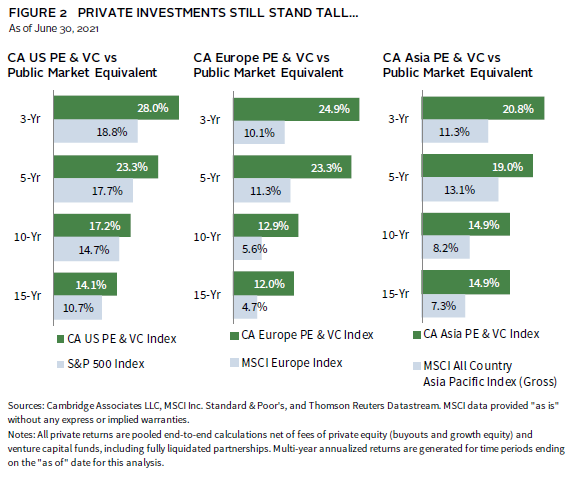

For investors of scale who have a long-term perspective and are willing to take on a measure of illiquidity, private investing (PI)—including private equity and venture capital (PE/VC)—can offer compelling long-term performance. As illustrated in Figure 2, PI has historically generated significantly higher returns than public equities.

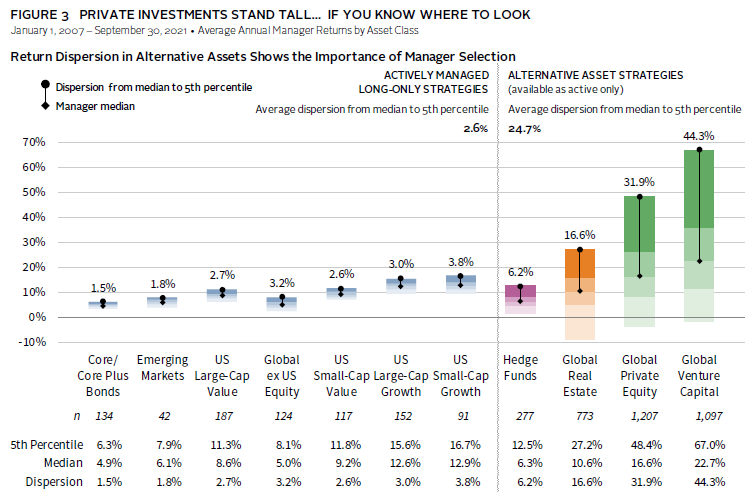

These opportunities, however, are not without risk. Among all asset classes, PI has experienced the greatest performance dispersion among managers. Figure 3 shows returns for the 15-year period ending September 2021. Over this timeframe, dispersion—measured as the difference in return between the top 5th percentile and median performing managers—for PE/VC was 31.9% and 44.3%, respectively, compared to a range of just 1.5% to 3.8% for public market asset classes. Therefore, the upside potential from allocating to PI also cuts the other way, with more downside from selecting underperformers. However, fear of ending up with bottom-quartile investments should not necessarily discourage investors. Rather, this downside risk should serve to underscore the importance of skilled investment selection.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Returns for bond, equity, and hedge fund managers are average annual compound returns (AACRs) for the 15 years ended September 30, 2021, and only managers with performance available for the entire period are included. Returns for private investment managers are horizon internal rates of return (IRRs) calculated since inception to September 30, 2021. Time-weighted returns (AACRs) and money-weighted returns (IRRs) are not directly comparable. Cambridge Associates LLC’s (CA) bond, equity, and hedge fund manager universe statistics are derived from CA’s proprietary Investment Manager Database. Managers that do not report in US dollars, exclude cash reserves from reported total returns, or have less than $50 million in product assets are excluded. Performance of bond and public equity managers is generally reported gross of investment management fees. Hedge fund managers generally report performance net of investment management fees and performance fees. CA derives its private benchmarks from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of private investment funds. The pooled returns represent the net end-to-end rates of return calculated on the aggregate of all cash flows and market values as reported to Cambridge Associates by the funds’ general partners in their quarterly and annual audited financial reports. These returns are net of management fees, expenses, and performance fees that take the form of a carried interest. Vintage years include 2007–2018.

Many entrepreneurs become familiar with PI as they grow their business. Some avail themselves of PI funding in early- and mid-stages of their business growth, while others invest directly in opportunities uncovered through their professional networks. Because PI may feel like familiar ground for some entrepreneurs, a word of caution is warranted. While it affords compelling growth opportunities, it also is a highly complex space. As with all asset classes, expert due diligence and strategic diversification are key to long-term success.

Put Your Unique Advantages to Work in the Market

While interesting investments can be identified through careful due diligence, accessing those investments can prove difficult. For example, some of the best opportunities often have constrained capacity, causing general partners (GPs) to be highly selective in choosing the investors they perceive as most desirable for their funds. When it comes to access, entrepreneurs sometimes have an edge.

Many business owners find that their reputation can be an asset. Industry knowledge, business acumen, and professional networks all can help to magnify an investor’s attractiveness to private investment GPs. As GPs consider interested investors for their next fund, for instance, they may value a business owner’s brand across multiple dimensions:

- Its ability to attract other investors or bring credibility to the fund;

- The connections it could offer through professional networks or other contacts;

- Domain expertise that could be useful in conducting due diligence for future investments; and

- Business synergies with the owner’s operating company.

See Andrea Auerbach, Rob Long, and Scott Martin, “Ready, Steady, Co-Invest,” Cambridge Associates LLC, March 22, 2019.

GPs also are increasingly offering co-investment opportunities to engaged limited partners (LPs) with relevant expertise—these can provide compelling value propositions at reduced fees and serve as another touch point for LPs to build rapport with GPs. For many entrepreneurs, the role of engaged PE/VC investor within their field of expertise can be a highly rewarding next act as they consider how to invest their capital.

4. Know and Account for Your Limitations

Most successful business owners share a common trait—they make smart decisions about people. They know the talents their firm needs and make sure they have the right people in place to deliver them. In contrast, delegating wealth management responsibilities can be a less intuitive and more challenging proposition.

Operating outside their field of expertise, entrepreneurs may not recognize the types of help they need to maximize investment opportunities, or how to best address the tax, legal, and other implications of owning significant wealth. Understanding which experts to engage with—attorneys, accountants, portfolio managers, financial advisors, philanthropic consultants, and others—is important, but so is determining which professionals are the best match for each individual or family’s unique personality and needs.

Perhaps even more difficult than assembling the right team can be relinquishing control to them. While entrepreneurs are experts in their specific fields, wealth management calls for different skills and knowledge. Letting go of some of the more technical or day-to-day decisions also can free the investor to focus on the bigger picture. By stepping back, they can turn their attention to stewardship—articulating their vision and goals, approving strategic policies and direction, monitoring results, and investing their time in pursuits that are most meaningful to them. These can include philanthropy, new business ventures, preparing the next generation for the responsibilities of family wealth, or other interests.

5. Plan Your Way to Victory

Company founders place great importance on sound planning. Yet often their business successes also came from their instincts and ability to adapt quickly. This may mean their company emerged piece by piece—rather than taking on multiple endeavors concurrently as part of a “master plan,” they instead began with a single idea and expanded opportunistically.

While this approach often is instrumental in the world of start-ups, it can lead to suboptimal outcomes, at best, and significant losses, at worst, in investment management. As owners consider how best to invest their hard-earned capital, they should recognize that, while great entrepreneurs may leap, great investors plan.

For more information on Cambridge Associates’ Family Enterprise Review and portfolio construction process, see Heather Jablow and Scott Palmer, “Portfolio Construction: A Blueprint for Private Families,” Cambridge Associates LLC, January 14, 2021.

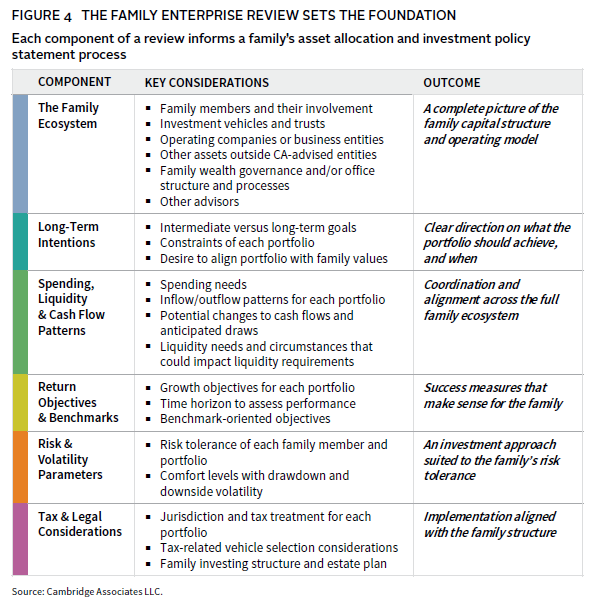

Establishing goals at the outset is essential to building, maintaining, and enhancing a large, diversified investment portfolio over time. The process should begin with a family enterprise review, which identifies the factors that shape each unique family wealth plan. As illustrated in Figure 4, these dimensions include a picture of the family capital structure, long-term goals, return objectives, and much more.

At the conclusion of this process, the investor’s plan can be further refined, beginning with policy setting—which entails the recommended asset allocation and drafting of a detailed investment policy statement. This statement provides guidelines for portfolio construction and forms the basis of the investor’s long-term strategy. Even though this plan will—and should—change over time, it enables clear alignment on what the entrepreneur and his or her supporting investment team have committed to achieve. From there, the most effective portfolio—customized to each family’s unique circumstances—can be managed to reflect changing needs and opportunities over time.

Conclusion

Creating and maximizing a business enterprise’s potential involve different attitudes, behaviors, and skills than are required to realize an investment portfolio’s full potential. Certainly, both successful business leadership and portfolio management depend on many similar traits, including conviction, expertise, hard work, and teamwork. But to be successful as an investor over the long run also can require some fundamental adjustments in mindset and direction.

In making this transition, an openness to new approaches and ideas is essential. It is likewise critical to set objective investment parameters early on, partner with experts one trusts, and—if appropriate and of personal interest—continue to leverage, as an investor in the private markets, the acumen and insights gained over a lifetime of business leadership. With these principles in place, entrepreneurs can be sure of continued success in this new stage of their life.

Jeff Bauer, Managing Director, Private Client Practice

About the Cambridge Associates LLC Indexes

Cambridge Associates derives its US private equity benchmark from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of private equity funds. As of June 30, 2021, the database included 1,297 US buyouts and growth equity funds formed from 1986 to 2021, with a value of $1.2 trillion. Ten years ago, as of June 30, 2011, the index included 770 funds whose value was $459 billion.

Cambridge Associates derives its US venture capital benchmark from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of venture capital funds. As of June 30, 2021, the database comprised 2,077 US venture capital funds formed from 1981 to 2021, with a value of $499 billion. Ten years ago, as of June 30, 2011, the index included 1,343 funds whose value was $122 billion.

The pooled returns represent the net end-to-end rates of return calculated on the aggregate of all cash flows and market values as reported to Cambridge Associates by the funds’ general partners in their quarterly and annual audited financial reports. These returns are net of management fees, expenses, and performance fees that take the form of a carried interest.

The Cambridge Associates Europe Private Equity and Venture Capital Benchmark shows multi-year returns for Cambridge Associates Private Investments benchmarks pulled from CMDB that are compounded returns. Multi-year returns reported by the Private Investments group are end-to-end. The end-to-end calculation is a periodic internal rate of return calculation that accounts for the beginning net asset value (NAV), the quarterly cash flows, and the ending NAV.

The Cambridge Associates Asia Private Equity and Venture Capital Benchmark shows multi-year returns for Cambridge Associates Private Investments benchmarks pulled from CMDB that are compounded returns. Multi-year returns reported by the Private Investments group are end-to-end. The end-to-end calculation is a periodic internal rate of return calculation that accounts for the beginning NAV, the quarterly cash flows, and the ending NAV.

About the Public Indexes

The MSCI AC Asia Pacific Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across five developed markets countries (Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand and Singapore) and eight emerging markets countries (China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand) in the Asia Pacific region.

The MSCI Europe Index is a free float–adjusted, market capitalization–weighted index designed to measure the equity market performance of the developed markets in Europe. It consists of the following 15 developed market country indexes: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

The S&P 500 Index measures the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. The S&P 500 is a capitalization-weighted index and the performance of the ten largest companies in the index account for 21.8% of the performance of the index. The average annual total return of the index, including dividends, since inception in 1926 has been 9.8%; however, there were several years where the index declined more than 30%.