In engaging with our family clients around the world, we are often asked for views on two related topics – how to think about philanthropy versus impact investing and how to best implement a socially and/or environmentally impactful investment strategy. Whilst common themes transcend these topics, each is distinct, and, as such, we will outline our perspective in a two-part series. In this piece, we discuss some of the motivations behind philanthropy and review how philanthropy relates to impact investing.

Philanthropy – Old Concept, New Use

Put simply, philanthropy can be regarded as the use of private capital for individual or public benefit. It is a concept that has been around for centuries, used not only to do good, but also to influence societal constructs, from religious institutions funding schools and hospitals as early as the seventh century to today’s billionaires donating to causes closest to their personal values. In so doing, philanthropists wield power directly over the recipients of their generosity and indirectly over a range of governmental and non-governmental organisations, including both private and charitable sectors. As a result, some have questioned the undue influence of philanthropists – and families should have this front of mind when considering philanthropy. Yet a recent study found that whilst 71% of family offices surveyed believed that they have a role to play in alleviating economic inequality, just 41% have a philanthropic strategy in place[1]Milken Institute, ‘Philanthropist’s Field Guide: Philanthropy in a Family Office,’ Milken Institute, June 2021., highlighting the need to align intent more thoughtfully with strategy in order to maximise effectiveness.

Many families’ philanthropic activities are, of course, linked to a deep sense of purpose and a desire to help humanity. However, the work often has several secondary purposes for families, including:

- To inform. Using philanthropy as an educational tool can be highly effective in informing the next generation of family values, including why the wealth exists and the responsibility of family members to manage it wisely.

- To involve. Philanthropy can serve as a great way to involve a wider group of family members by asking them to contribute in some capacity. This could take the form of a high-level discussion about where the family should focus their philanthropic endeavors or, at a more granular level, by encouraging family members to research giving opportunities within an area of personal interest. Here we often see the younger generation driving the conversation and educating matriarchs and patriarchs around topics such as climate change and social justice.

- To inspire. By informing and involving, philanthropic initiatives often inspire both old and young to do more, and so the endeavors become embedded within the family value set, evolving into a self-fulfilling process that can be passed on to future generations.

These ‘three I’s’ – inform, involve, and inspire – can amplify a desire to give back to society by collectively providing families with a strong clarity and purpose to engage. However, a fourth element can also be particularly relevant to families: tax incentives. Whilst taxes are unlikely to be the driving force in motivating families to give money away, they can be an incremental consideration as they incentivise donors who are high taxpayers to ‘do good’ while reducing their tax burden – a win/win for donor and recipient. However, the calculation is more mathematical for governments – tax concessions will be justified if they result in a larger increase in social welfare than what the government could have otherwise achieved through direct spending.

Regardless of the motivations behind philanthropy – which may be multiple and as unique as each family – philanthropy typically exists as a distinct cause outside of the remit of the family investment portfolio. Yet the disciplines of philanthropy and investing are connected, as the annual proceeds from a traditional investment portfolio may be used to fund philanthropic causes. Therefore, philanthropy is often included alongside investment strategy in an early conversation with families. Because of this, the distinction between the two concepts can become blurred.

Impact Investing – A New Concept

Please see Nick Rees, ‘Implementing a Sustainable and Impact Investing Strategy – A Family Perspective,’ Cambridge Associates LLC, July 2022.

Whilst philanthropy has a long history, impact investing is a much newer concept that has only really gained significant traction in the last decade. But what is impact investing? Simply, impact investments are investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return[2]Global Impact Investing Network, ‘Impact Investing,’ Global Impact Investing Network, June 2022.. This last point – requiring a financial return – is important, as it clearly differentiates impact investing from philanthropy, where no financial return is required. In the second paper of this series, we explore how much of a financial return is needed and whether there is a trade-off between financial and social/environmental returns.

For more information, please see Liqian Ma and Tom Mitchell, ‘Pathways to Sustainable Investing: Insights from Families and Peers,’ Cambridge Associates LLC, July 2019.

The International Finance Corporation estimates that impact investments totaled $2.3 trillion in 2020, equivalent to about 2% of global assets under management[3] Ariane Volk, ‘Investing for Impact: The Global Impact Investing Market 2020,’ International Financial Corporation, July 2021.. While likely an underestimate, this is still a relatively small amount. However, impact investing is a growing area and is seen by many families as being a particularly important part of the world’s recovery from the protracted economic, social, and environmental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Impact Beyond ESG

The concept of investing without doing harm via environmental, social, and governance (ESG) best practices is now widely familiar, but it is often regarded as synonymous with impact investing. This is not the case; in fact, impact goes further than ESG, being distinguished by three practices:

- Intentionality. In impact investing, it is insufficient to be ‘less bad.’ Instead, investments must be intentionally good, such as to advance public welfare.

- Measurement. While ESG and impact investing share the intention to deliver positive impacts, the results in the case of impact investing must be quantified via rigorous measurement. This can be extremely difficult, as measuring long-term outcomes (as opposed to shorter-term ‘outputs’) is complicated by numerous other potential influencing factors. Doing it well is key in attracting additional capital, which can then help scale positive outcomes.

- Contribution to solutions. In providing a financial return on investment, impact investments aim to attract a distinct additional capital pool that might not otherwise exist, creating a ‘market-based’ solution. Whilst some debate whether private profits should be made on capital delivering public benefit (as the public benefit could be higher if profits weren’t extracted), the counterargument here is that without the market-based mechanism, solutions can become difficult to scale.

A great example of this is M-Kopa, a private, African-based business launched in 2010 with the aim of transitioning families away from the use of toxic, open-flamed kerosene lanterns to clean, solar-powered solutions. Fast forward 12 years and M-Kopa has developed to also become a microfinance platform (used to give access to the solar technology) with six offices, more than 1,000 employees, and more than 1 million customers. Most impressively, however, has been the company’s ability to quantify its impact: 3.7 million lives improved, $498 million saved from fuel displacement, 168,000 individuals connected to the internet for the first time, and 2 million tonnes of CO2 avoided.

An Opportunity to Be Catalytic

Please see Erin Harkless and Rebecca Carland, ‘The Foundation of Good Governance for Family Impact Investors: Removing Obstacles and Charting a Path to Action,’ Cambridge Associates LLC, September 2016 for more information.

As M-Kopa demonstrates, early investors in impact-focused businesses have a unique opportunity to be a catalyst for others. Specifically, a greater social impact is potentially available to families who can be nimble in their decision-making and focused in their implementation.

With regard to specific opportunities, The Global Impact Investment Network cites sectors such as sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and microfinance as particularly ripe for impact investing, as well as the provision of basic services such as housing, healthcare, and education. The challenge here then is not in identifying investments in these sectors – of which there are many – but rather in recognising the most compelling investment opportunities that align with one’s values.

Philanthropy and Impact Alignment

Although they are distinct concepts, philanthropy and impact investments are holistically aligned – ultimately, the purpose of both capital pools is to influence positively. However, some have expressed criticism that the growth of impact investing is cannibalising a relatively scarce pool of philanthropic capital, focused on a limited opportunity set. The ideas that follow dispel this myth:

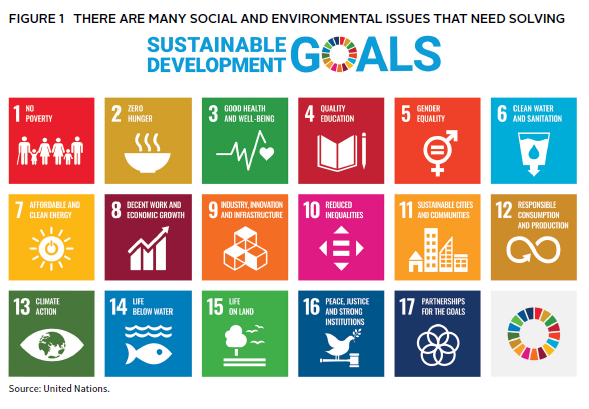

- The world isn’t short of problems. The existence of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), shown in Figure 1, is a reminder of the extent to which there are deep social and environmental issues that need solving. Although the limited availability of data makes SDG needs assessments difficult, the world’s financial requirements for achieving the SDGs are estimated to be between $5 trillion and $7 trillion per year between now and 2030[4]Vanessa Fajans-Turner, ‘Filling the Finance Gap,’ United Nations Association – UK, June 2019.. Combining all forms of philanthropy, development capital, and impact investments still leaves us short by some $2 trillion per year. In other words, there is room for both.

- There is plenty of global wealth. The world’s net worth, as measured by the value of real assets, has risen by some $350 trillion in the past two decades[5]Jonathan Woetzel, Anu Madgavkar, and Jan Mischke, ‘Global Wealth Has Exploded: Are We Using It Wisely?’ Barron’s, November 2021.. As wealth accumulation has accelerated – fueled by technological developments – so too has the potential for philanthropists to really make a difference.

- Differing intent. Philanthropy and impact investing are fundamentally different. First, in theory at least, philanthropic capital is unconstrained; without the requirement for any sort of financial return on investment, it can be invested anywhere. The opposite is true of impact investments, which must focus on those sectors where the capital can be impactful and profitable.

Second, impact capital can be used as ‘proof of concept’ capital, such that larger pools can follow. In other words, one of the goals of impact investing is to attract other financial investors by proving an investment is impactful. Without proof, this capital would likely never enter the space, and so a funding gap would remain. Although it could also be argued that some philanthropists have the same goal, it is not a generalisation that can be made across the sector.

Family Philanthropy and Impact

In this paper, we have sought to highlight that just as the evolutions of philanthropy and impact investing are quite distinct, so too is their place in family wealth management toolkits. This distinction presents an opportunity by allowing families to engage in a powerful combination of both, giving clarity of meaning and purpose to family members across generations without cannibalising the effects of either strategy.

That said, recognising the nuanced differences between the concepts of philanthropy and impact investing is important if implementation is to be efficient and effective. Whilst grey areas still may occur, inefficiencies can be minimised by focusing on the internal and external intentions of each and remembering that although both capital pools seek to measurably contribute to solutions, impact investing requires a financial and social return, whilst philanthropy only requires the latter.

Nick Rees, Managing Director, Private Client Practice

The other paper in this two-part series, Implementing a Sustainable and Impact Investing Strategy – A Family Perspective, addresses how to implement an effective impact-based portfolio strategy.

Footnotes