- Currency risk is a fact of life for investors, yet few have given appropriate thought to setting a strategic hedging policy. In an ideal scenario, investors could simply integrate currency decisions into their investment process, purposefully taking attractive currency exposures and avoiding unattractive ones. The reality is much more complex, as currency exposures are often not intentional, but rather a consequence of asset allocation choices.

- The typical approaches to currency hedging are useful to an extent but have material drawbacks: they are either too simplistic, relying purely on qualitative assessments based on broad asset class characteristics while ignoring currency market nuances, or, at the other end of the spectrum, too complex and dependent on inherently unstable assumptions regarding the risk/return behaviour of currencies.

- Our framework achieves an attractive balance by seamlessly integrating qualitative portfolio considerations driven by relevant asset class characteristics with a highly simplified yet robust method of incorporating individual currency characteristics. Further, the framework integrates behavioural considerations that invariably cloud strategic thinking on currency hedging. The framework has the additional advantages of retaining simplicity of policy formulation and providing a clear path to implementation.

- The framework is applicable to a broad set of investors despite differences in risk appetite, portfolio structure, home currency characteristics, or governance resources. Additionally, it accommodates the inherent lack of precision in measuring currency exposures and calibrating expected returns/risk implications from currency hedging, and enables comprehensive consideration of cost/benefit trade-offs by separating the question of implementation from strategic policy setting. Finally, it provides flexibility to tilt the portfolio on a tactical basis, if investors have a strong view on particular currencies.

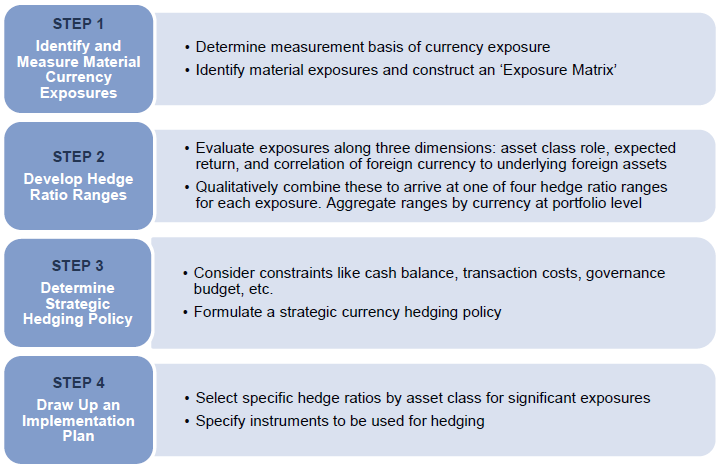

- We show how the framework can be applied using a clear four-step process. In the first step, the investor identifies relevant currency exposures and constructs a portfolio exposure matrix. The second step is to develop hedge ratio ranges based on evaluation of three considerations: asset class role and characteristics, expected returns from currency hedging, and currency pair/asset return correlation. In the third step, constraints that apply to the specific investor are considered to determine an appropriate strategic hedging policy. In the final step, the strategic currency policy is translated into a practical implementation plan, where minimizing cost and complexity are the main considerations.

- By applying the framework, investors can set strategic currency policy in an analogous way to strategic asset allocation, with target currency exposures and tolerance ranges around the target. This not only helps to achieve consistency over time in the treatment of currency exposures, but can also help to clearly distinguish between strategic exposures and tactical overlays.

In today’s increasingly global capital markets, most portfolios have foreign currency exposures, making currency risk a fact of life for investors. In most cases, this currency risk is simply a residual of other portfolio management decisions. However, the order of magnitude of exposure to a single exchange rate can be significant, often greater than 10%, which can be larger than exposures to other risk factors. As a result, the rewards or costs for making the right or wrong currency hedging decision can overwhelm other performance drivers.

Yet investors often struggle with weaving currency risk into the management of their investment portfolios, as it does not fit neatly into the traditional long-term risk/return framework. The long-term expected return (if any) is often small, while the potential medium-term volatility introduced by foreign currency exposures is high. It is often not practical or desirable to eliminate this risk completely, however, as currencies can provide diversification benefits. Currency hedging programs can address these risks, but investors face several dilemmas when designing these programs. In addition to traditional investment risks, these programs can also introduce significant behavioural risks which cannot be ignored.

As an outgrowth of, and improvement on, more traditional approaches to currency hedging, this report outlines a new framework for developing a strategic currency policy and illustrates its application with a four-step process:

- Step 1: Identify and Measure Material Currency Exposures

- Step 2: Develop Hedge Ratio Ranges

- Step 3: Determine Strategic Hedging Policy

- Step 4: Draw Up an Implementation Plan

Our holistic approach integrates consideration of the underlying portfolio’s characteristics, the actual market-based risk/return profile of each foreign currency exposure, and the behavioural risk associated with currency hedging programs. Importantly, the framework allows for both qualitative and quantitative considerations while also accommodating imperfect knowledge of currency exposures. As a result, it provides a wider tool set for investors to determine whether to hedge or not, depending on the magnitude of the foreign currency exposures and the characteristics of these risks relative to their base currency.

Our framework allows the investor to express strategic currency hedging policy in the form of a set of hedge ratio ranges by currency for those currencies to which the investor is materially exposed—analogous to having ranges around a traditional strategic asset allocation. This approach ensures consistency with portfolio objectives and the market environment, and reduces the behavioural risk that can arise from the temptation to make significant changes to currency policy immediately after large moves in the market. It also permits considerable flexibility in the hedging implementation plan, which can address practical constraints like managing the cash flows arising from a currency hedging program, and provides investors a way to incorporate specific views on a currency pair.

In the sections that follow we review typical approaches to managing currency risk, provide an overview of our new framework, and use a sample portfolio to illustrate how investors can apply it in four simple steps. In the appendices, we offer additional detail on how asset classes’ characteristics or role in the portfolio influence currency hedging decisions; discuss empirical observations on the expected return on currencies; provide a discussion of the theory underpinning the integration of behavioural considerations into the framework; and examine the use of FX forwards for currency hedging. A glossary at the end of this report defines key terms.

Typical Approaches to Managing Currency Risk

In an ideal scenario, investors could simply integrate currency decisions into their investment process, purposefully taking attractive currency exposures and avoiding unattractive ones. In practice, several barriers impede such a simple process, not the least of which is that currency exposures are often not intentional, but rather a consequence of asset allocation choices. In addition, removing unwanted exposures may be costly, requiring ongoing cash settlements to be monitored and funded, which may result in a cash drag on performance. The perceived additional risk with no commensurate long-term return that currency exposures present has traditionally led investors to focus on minimising their exposure. This is in contrast to the more balanced manner in which investors evaluate most other market risk factors in their portfolios—by making choices between various combinations of risk and return.

Investors with globally diversified portfolios typically use one of three approaches to managing currency risk (Figure 1). In the most basic approach, investors apply a single hedge ratio uniformly to all currency exposures, or specify the minimum desired exposure to their home currency, and then partially or fully hedge the largest foreign currency exposures. A second, ‘asset class–centric’ approach is to examine the role of each asset class in the portfolio and fully hedge those exposures intended to help lower volatility in the portfolio (e.g., fixed income) while not hedging or only partially hedging asset classes with other roles. Finally, in a ‘currency-centric approach,’ the investor seeks to precisely quantify the impact of each currency exposure on the portfolio’s risk/return profile, typically using an optimisation scheme, such as mean-variance.

Each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages and is best suited for a particular circumstance as summarised in Figure 2. Our framework builds on these typical approaches to take the investor through a series of exercises and analyses that will ultimately lead to a strategic hedging policy.

New Framework for Determining Strategic Currency Policy

Our goal was to develop an integrated approach to currency hedging that incorporates the most attractive features of the three typical approaches, while avoiding their most limiting drawbacks. In particular, we looked for a solution that would:

- Consider both the asset class and underlying currency exposure characteristics relative to an investor’s home currency;

- Integrate behavioural considerations;

- Retain simplicity of policy formulation; and

- Provide a clear path to implementation.

Our new framework achieves all of these objectives, and we show how it can be applied using a four-step process summarised in Figure 3.

As we describe the process in the pages that follow, we use a sample portfolio that is diversified by asset class and region and that has a mix of internally and externally managed components to illustrate the results of each step of the process.

Although in our example this portfolio’s home currency is the British pound (GBP), the framework is applicable to investors in any currency domicile. Figure 4 shows the current portfolio for this illustrative investor. Note that we show allocation not only by asset class, but also by ‘role in portfolio’ (e.g., growth drivers), which is one of the factors we will evaluate when determining hedge ratio ranges.

Step 1: Identify and Measure Material Currency Exposures

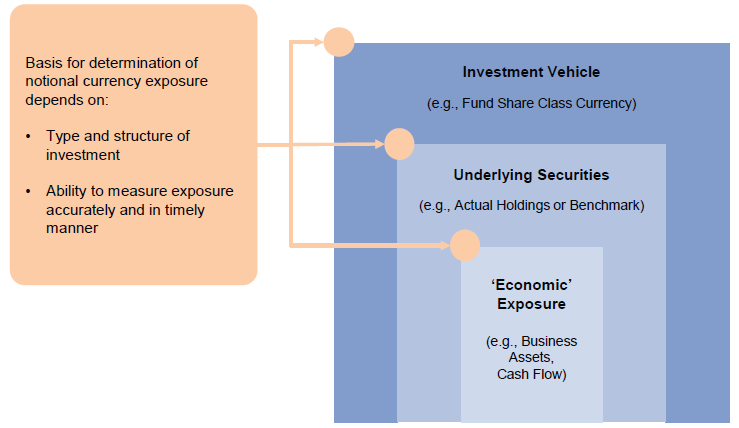

We first address how to measure the foreign currency exposure to be hedged, which can be hard to do for complex portfolios. Currency risk can arise from many sources in an investor’s portfolio, some more transparent than others. The most obvious are foreign equity or bond holdings not denominated in the investor’s home currency. Less obvious might be a domestic stock investment in a multinational company that earns a large proportion of its profits in foreign countries. Alternative investments like hedge funds may have investments with exposures in various currencies that are not transparent to investors, and which may or may not be hedged. Measuring the exact amount of currency exposure in a portfolio in a timely manner is challenging, and investors must decide what is most relevant, and on what basis to measure the exposure to a particular currency within the portfolio. We follow the adage that management of currency risk can be done with no more precision than measurement of that risk.

Methods for Measuring Currency Exposure

To identify the currency exposure in their portfolios, investors can use a look-through process at different levels, as shown in Figure 5, and each approach is described in the pages that follow. Different levels of assessment are likely needed for the various holdings within a portfolio.

Investment vehicles’ currency denomination. In the case of externally managed investments, when considering currency risk at the fund share class level, investors should focus simply on the currency risk arising from the difference between the effective denomination of the investment (e.g., USD for a USD share class of a hedge fund) and the home currency for the investor (e.g., GBP for a UK-based investor with spending needs primarily in GBP). This is likely most appropriate when the manager is explicitly incentivised to maximise returns in the currency of the investment vehicle, and thus active management of currency risk is reliably delegated to the manager. A hedge fund whose performance fee is based on performance accruing to the investor in USD, for example, can be thought of as a single foreign currency exposure to USD versus the home currency of the investor.In such a situation, the investor can expect to know the exposure measured at this level with a good degree of accuracy in a timely manner by simply looking at the latest available net asset value of the fund without the need for underlying exposure data.

This approach is simple and effective, and the most popular one with respect to highly active managers and strategies in a multi-manager portfolio where performance-related incentive fee structures are in place.

Underlying securities’ currency denomination. In the case of some investments held through externally managed funds, investors may look through to the currency exposures as determined by the holdings of the funds, particularly those without an explicit incentive fee in a particular currency. In such circumstances, investors may not be able to rely on the manager to actively manage currency risk. In fact, asset managers in this category often shy away from actively managing currency risk even if their mandate allows them to employ currency hedging. Where the manager is simply running a passive portfolio referencing a known index, the solution is to assume the portfolio has similar exposure to the benchmark. At the other end of spectrum, where the manager is running a highly active, bottom-up, research-driven, concentrated portfolio of 20 to 30 stocks without reference to any benchmark, this is a matter for the judgment of the investor. The currency hedge may either be based on the exposures of an artificial benchmark that the investor thinks is appropriate for the manager or based on actual exposures provided by the manager. Similarly, with directly held securities, investors should focus on the currency risk between the denominational currency of the security versus their home currency except in specific circumstances as discussed in the next section.

Looking through to the security level is appropriate as long as the investor can be confident that this results in a fairly accurate estimate of currency exposures in a timely manner. The main caveat regarding the use of a benchmark is that it might be wholly inappropriate for the manager. Similarly, the caveat with using actual holdings data is that the data might be dated when received from the manager and quite inaccurate in the case of highly active managers. If the manager is known to take long-term positions, then using holdings data for currency exposure calculations will likely be most appropriate. If the manager trades heavily, then using a market index benchmark may be more suitable. When currency exposure is aggregated across the portfolio, however, the investor should acknowledge the potential for estimation errors around actual currency exposure in setting hedging policy.

‘Economic’ exposure. Currency exposure is transmitted to the end investor through numerous links in a chain. One might argue that the true currency risk arises from the actual economic activities of the company that issues the shares or bonds held by the investor and that investors should measure such currency exposures as well. This method might be appropriate for a portfolio dominated by a single company, where a look through to the underlying economic exposure may be needed to determine currency hedging policy. In such cases, deeper analysis may be warranted and may require consultation with the investee company itself—where it may emerge that having the investee company undertake hedging at the corporate level is more efficient than leaving that exposure for shareholders to bear and manage.

Our view is that attempting to hedge risks at this level is not advisable, except in very rare circumstances. Even if the investor—through considerable effort—were able to arrive at some estimate of the currency exposure from investing in each underlying company in the portfolio, can the investor (a) have enough confidence in the quality of this estimate, and (b) afford to devote resources to making this estimate repeatedly through time? The answer is most likely no. Given the potential for large estimation error, this approach is rarely usable in practice.

Figure 6 summarises these three approaches to measuring currency exposure.

Construct a Portfolio Exposure Matrix

Once relevant exposures have been identified, these can be set out as a matrix of investment holdings and foreign currencies. This is illustrated in Figure 7 using our example investor, whose home currency is GBP. Through the approaches just described, the currency exposure in each case has been determined by using the vehicle share class, the allocation’s benchmark as a proxy, or actual holdings data. Exposure in hedge funds, for example, was determined using the fund share class currency. Exposures for developed markets equities use a mix of actual holdings for some managers—for example, a manager with a concentrated portfolio that is very different from the benchmark in its security and regional exposure, where the manager does not manage currency exposure and the holding period for positions is expected to average three to five years—and the relevant equity benchmark exposure for others.

Hedging minor currency exposures may not be feasible unless a low cost option is available. A globally diversified portfolio will typically see most of its exposure concentrated in a few currencies accompanied by a potentially long tail of minor currency exposures that are unlikely to be material to the case for currency hedging. In our experience, for most typical portfolios oriented towards modest capital appreciation, any currencies to which aggregate portfolio exposure is below 2% are unlikely to be material.

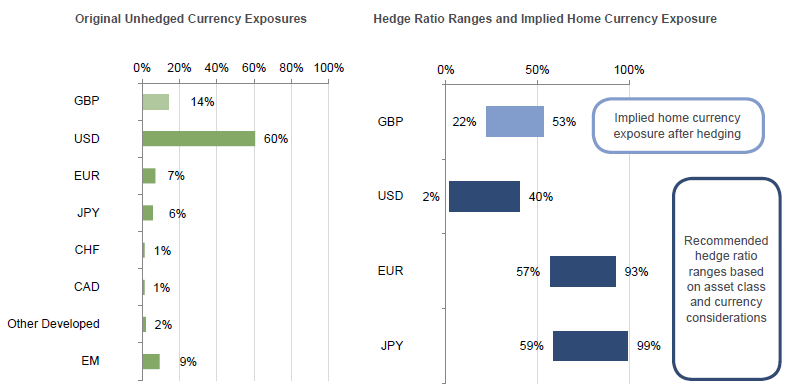

Taking this into account, the exposure matrix for our illustrative UK-based investor shows that only 14% of the unhedged portfolio is in the home currency (GBP), and the portfolio has three material exposures to developed foreign currencies, the largest of which is in the USD at 60%. Note that emerging markets currencies have been aggregated in this case as none of them account for more than 2% of the portfolio. Investors may disaggregate emerging markets exposures into individual currencies when these are larger and more material.

Step 2: Develop Hedge Ratio Ranges

For each material foreign currency exposure in the portfolio, an investor may choose to hedge anywhere from 0% to 100%. This range can be narrowed to be more specific for each foreign currency/asset class combination on the basis of three considerations:

- Asset class role and characteristics,

- Expected return (if any) from the currency hedge, and

- Correlation of foreign currency to underlying assets.

This is where our framework achieves a substantial simplification in the process of setting currency policy, as we partition the range of possible hedge ratios into four choices:

- Do Not Hedge: 0%

- Hedge Some: 0%–50%

- Hedge Most: 50%–100%

- Fully Hedge: 100%

Each exposure is evaluated against the three considerations above. When the asset class characteristics and role in the portfolio are dominant considerations for an exposure, we apply hedge ratio choice 1 or 4, i.e., no hedge or a full hedge. Where currency characteristics like expected return and correlation to underlying characteristics are the dominant consideration, it is a choice between hedging some or hedging most. The rationale underpinning these choices is discussed in the following sections.

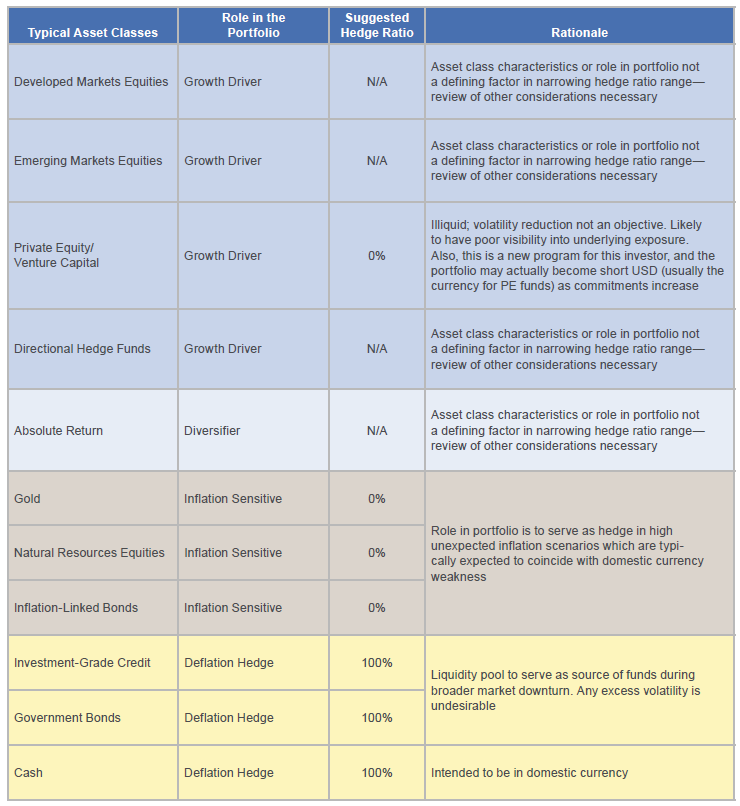

Consideration (a): Asset Class Role and Characteristics

The characteristics and role of an asset class in the portfolio can be the dominant consideration in deciding how much to hedge. For example, asset classes expected to be volatility dampeners and a source of funding to rebalance the portfolio during periods of risky asset drawdowns are more likely to be hedged 100%. Conversely, asset classes explicitly expected to be correlated with depreciation of the home currency (e.g., inflation-sensitive assets) can be left wholly unhedged (hedge ratio of 0%). For some asset classes, the role in portfolio doesn’t clearly indicate a hedge ratio preference, and the investor may need to move on to the next two consideratons to provide more guidance. Appendix A discusses further the relationship between the characteristics and role of major asset classes in the portfolio and the implications for the currency hedging decision regarding that asset class.

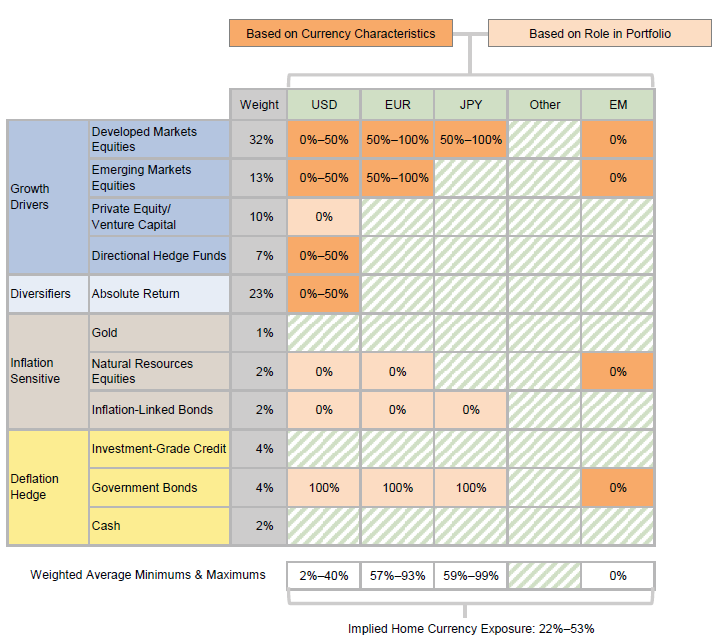

In the particular example of our GBP-based investor, the implications of asset class considerations are summarised in Figure 8.

Consideration (b): Expected Returns From Currency Hedging

Long-term assumptions about risk and return for specific foreign currencies versus the investor’s home currency should influence the investor’s currency hedging approach. The traditional rational investor would seek to maximise ‘utility’ by optimising the currency exposure to achieve some estimated maximum risk-adjusted return. The investor would develop long-term assumptions about currency risk premia (i.e., long-term returns), volatility, and correlations, and then determine the right mix of currency exposure to achieve this objective. This approach is well documented in traditional literature[1]See, for example, Mark Kritzman, ‘The Optimal Currency Hedging Policy with Biased Forward Rates,’ The Journal of Portfolio Management, vol 19, no. 4 (1993): 94–100. using mean-variance optimisation techniques.

However, estimating the ‘expected return’ from a foreign currency hedge is not a trivial task. In fact, many investors assume that currency returns average to zero over the long term. Empirical data suggest otherwise, with evidence that an investor can expect to systematically earn a risk premium for bearing currency risk in two particular cases.

The first is the so-called forward rate bias puzzle. A long-standing, empirically validated observation[2]See for example, Lucio Sarno, ‘Towards a Solution to the Puzzles in Exchange Rate Economics: Where Do We Stand?,’ Financial Econometrics Research Centre, 2005 and Eugene Fama, ‘Forward and Spot … Continue reading in currency markets is that being long currencies with higher interest rates and short those with low interest rates has been a positive total return strategy[3]Total return includes the implicit rates of interest earned and paid on the currencies that the investor is long and short, respectively. over the long term. Figure 9 shows one simple example of a single exchange rate: GBP/JPY. The GBP/JPY exchange rate has indeed not changed very much over 20 years, but the total return from being long GBP and short JPY has amounted to as much as 2.2% per annum. Interest rates in GBP have been consistently higher than those in JPY during this period. This is an example of what is popularly called the ‘carry’ trade.[4]Positive carry is when an investor is long a country with higher interest rates and short a lower interest rate country.

Figure 9. Comparing the Exchange Rate of GBP/JPY to the Pair’s Total Return

3 January 1994 – 31 December 2015

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

The second case is currencies of emerging markets countries. These have exhibited higher positive returns for investors with developed economy base currencies. In addition to high interest rate differentials, this trend reflects the benefit of the real appreciation of emerging market currencies, which is known as the Harrod-Balassa-Samuelson effect. As a result we typically recommend a 0% hedge ratio for emerging markets currencies due to the carry and frictional costs associated with hedging such exposure. We provide further discussion on expected currency returns in Appendix B.

The natural question to ask is whether an investor can develop estimates of expected long-term return and risk for each currency. The answer, unfortunately, is not with any confidence. Sophisticated models of currencies developed over one period have been shown to have poor predictive power over subsequent periods. Even longer-term studies are confounded by the constant change in currency regimes across the world.

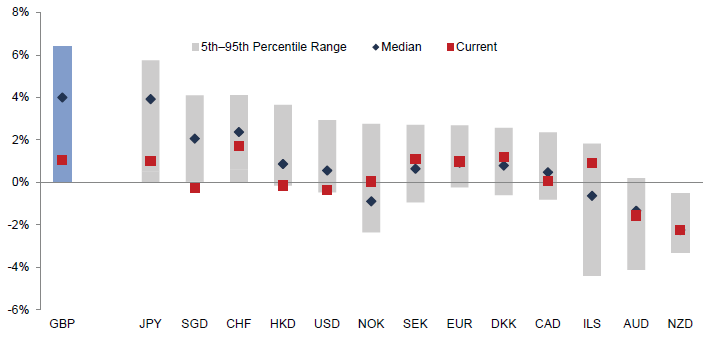

The good news is that our currency hedging framework only requires the investor to know the sign of the expected return (i.e., positive or negative) and whether the expected return is of a meaningful magnitude. If the investor has fundamental views on the foreign currency, these can drive determination of expected return. If the investor does not have particular views, empirical research suggests that the investor can use the expected ‘interest rate carry’ from hedging as a proxy for the expected return from hedging, especially if the only objective is to know the sign and get an approximate idea of the expected return’s magnitude. For example, the investor can compare the prevailing 12-month interest rates in each foreign currency to the home currency as the measure of carry. In addition, the investor may determine that in a low interest rate environment, an interest rate differential greater than +/-1% should be considered a meaningful amount of carry and a reasonable indicator of expected return from hedging. Anything smaller may be considered insignificant.

Figure 10 shows the relative interest rate carry environment faced by a GBP-based investor versus other developed markets currencies (the leftmost bar is simply the range of 12-month interest rates in GBP). Notably, hedging NZD has been consistently a negative carry trade and AUD nearly always so, while hedging JPY, SGD, and CHF have consistently been a positive carry trade. The implication is that for the GBP-based investor, if carry is used as a proxy for expected return, the expected return from hedging is non-zero for certain foreign currencies, which should be taken into account when making hedging decisions.

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

Notes: The initial bar reflects the range of 12-month interest rates in GBP while the rest reflect the interest rate differential between GBP and the respective currency. All are based on data between November 2003 and December 2015.

Interest rate carry can only provide an indication of expected return from hedging. Over short time horizons, it is still hard to have high confidence in the predictability of returns from currency exposure. Currency volatility can often obscure and overwhelm any pattern of returns. An investor adopting all or nothing hedge ratios (0% or 100%) on the basis of forward-looking estimates of expected risk/return for currencies could see a large impact on total portfolio returns, which can introduce behavioural vulnerabilities. For example, investors experiencing consistently large negative returns from a currency hedging program might abandon the program, often at precisely the wrong time. This is a result of ‘regret’ induced by noting how much better the investor might have done without the currency hedge. The following section discusses how to build defences against these behavioural vulnerabilities within the currency hedging program by explicitly avoiding ‘all or nothing’ hedging decisions in favour of hedge ratio ranges that are softly guided by expected return/risk and the desire to minimise regret.

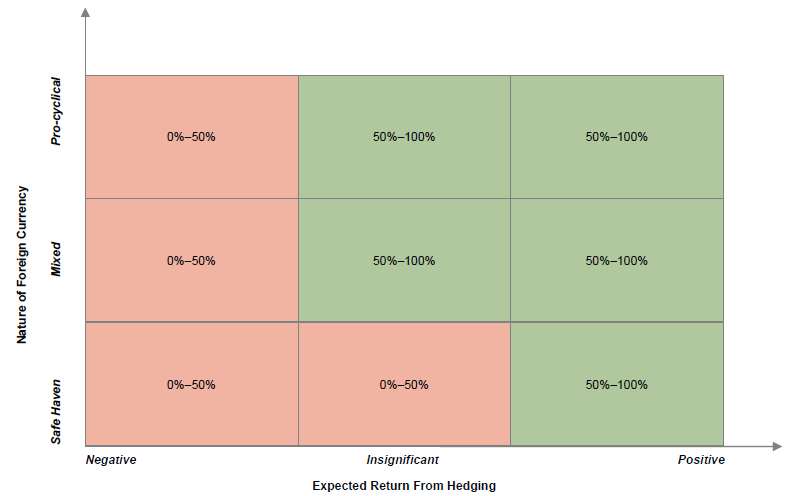

The Importance of Regret. Regret refers to the emotion felt by investors when a decision in the past (e.g., the decision to hedge or not to hedge currency risk) resulted in a bad outcome, and a decision with a better outcome could have been made in hindsight. An investor that is infinitely regret averse with respect to the currency hedging decision would always choose a hedge ratio of 50% as this would minimise regret regardless of whether the currency hedge turns out to be profitable or not. The theoretical work of Sébastien Michenaud and Bruno Solnik[5]Sébastien Michenaud and Bruno Solnik, ‘Applying Regret Theory to Investment Choices: Currency Hedging Decisions,’ Journal of International Money and Finance, vol 27 (2008): 677–694. considers an investor that is simultaneously both risk averse and regret averse but the relative importance of risk versus regret aversion is unknown. Two rules of thumb that can be drawn from this work enable us to integrate regret into our framework by recommending the following:

- If the investor expects a positive return from currency hedging, then the investor’s optimal hedge ratio is between 50% and 100%.

- If the investor expects a negative return from currency hedging, then the investor’s optimal hedge ratio is between 0% and 50%.

In each case, 50% is the hedge ratio that minimises regret, while 0% or 100% maximises risk-adjusted return depending on the expected return on the currency hedge (Figure 11). These rules are intuitively appealing as it would be natural to hedge more (less) if the investor expects to make (lose) money from hedging. For those interested in the theoretical basis for these rules, we provide a discussion of Michenaud and Solnik’s result in Appendix C. In addition, the discussion in Appendix C clearly illustrates the relative influence of risk aversion/regret aversion and currency characteristics like expected return, volatility, and correlation to risky assets.

Before assessing how the expected return from currency affects our illustrative investor, we first turn to the final consideration, which, combined with expected return, helps narrow hedge ratio ranges for each material currency exposure.

Consideration (c): Currency Pair/Asset Return Correlation

The other currency characteristic to consider is the correlation behaviour of the foreign currency with respect to foreign assets. Consider a scenario where there is a very modest positive expected return from carry, yet the foreign currency in question actually provides a diversification benefit due to its negative correlation with foreign assets. In such a scenario, it might actually be preferable to adopt a low hedge ratio (0%–50%) and ignore the very modest positive expected return from hedging.

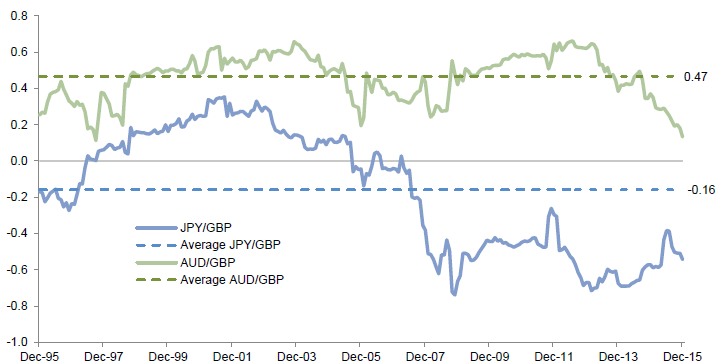

To assess the nature of the currency pair, we use a simple heuristic that classifies currencies into three different types based on their correlation with the return on underlying foreign risky assets, measured in the home currency. If the expected correlation of the foreign currency exchange rate[6]Expressed as units of home currency per unit of foreign currency. to the underlying foreign risky assets is meaningfully negative, the foreign currency is classified as a ‘safe haven,’ whereas if the correlation is meaningfully positive, it is classified as ‘pro-cyclical.’ Otherwise, the foreign currency is classified as having ‘mixed’ characteristics. While a currency could change its ‘character’ over time, this usually happens slowly, as such a change would be driven by fundamental factors that played out over very long time frames.[7]Although investors should be mindful that fundamental factors can be overruled and rapid regime changes can occur, as in the Swiss National Bank’s adoption of a floor for EUR/CHF in 2011 and its … Continue reading

To determine which correlation type best describes a foreign currency versus a given home currency, historical correlation data and other techniques such as cluster analysis are used. For example, Figure 12 illustrates the behaviour of two currencies (JPY and AUD) versus GBP. The correlation between JPY/GBP and MSCI World (local currency) is negative, particularly in recent times, suggesting that JPY behaves like a safe-haven currency versus GBP. Conversely, the data show a strong and persistent positive correlation of AUD/GBP versus MSCI World (local currency), which suggests AUD is a pro-cyclical currency compared to GBP.

Figure 12. 36-Month Rolling Correlations: AUD/GBP and JPY/GBP vs MSCI World

31 December 1995 – 31 December 2015 Local Currency

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided ‘as is’ without any express or implied warranties.

Combining considerations (b) and (c)—evaluating a currency’s expected return and a currency’s correlation behaviour characteristics and applying the rules of thumb introduced earlier—creates a currency characteristics matrix that shows which hedge ratio range is most appropriate based on the combination of these two factors (Figure 13).

Figure 14 provides matrices for three major base currencies—GBP, USD, and AUD—versus G-10 and emerging markets currencies.

Figure 14. Currency Pair Matrices for GBP, USD, and AUD Home Currencies vs G-10 and EM Currencies

As of December 2015

We can now easily apply these currency considerations to our illustrative UK-based investor. Combining the GBP currency pair matrix with the hedge ratio currency characteristics matrix, the investor arrives at hedge ratio ranges for the major currency exposures (Figure 15).

Putting It All Together: Determining the Appropriate Hedge Ratio Ranges

Having evaluated the asset class characteristics and roles along with currency characteristics (expected return and correlation with the underlying risky assets), each cell in the exposure matrix can now be assigned one of the four hedge ratio ranges. In some cases, the role of the asset class in the portfolio will be the dominant consideration, while in other cases the particular characteristics of the foreign currency will matter most. We show in Figure 16 how these three considerations have influenced our sample UK-based investor’s choice of hedge ratio ranges.

Note: Striped boxes indicate either no exposure to the currency for that asset class or, in the case of other currencies, zero or immaterial exposures for this portfolio.

The investor can now determine the minimum and maximum hedge ratio for each foreign currency by calculating a weighted average for each foreign currency. Using our sample UK-based investor, note that the hedge ratio range calculated for USD in Figure 16 is 2%–40%. For the lower limit, the contribution only comes from the deflation hedges, where the investor has chosen a 100% hedge for any USD exposure arising from this allocation. The upper limit of about 40% is a weighted average arising from the 50% upper limit for USD exposure in developed and emerging markets equities and directional and absolute return hedge funds, along with the 100% hedge ratio for the government bond allocation.

Step 3: Determine Strategic Hedging Policy

Having identified the investor’s material currency exposures in Step 1 and determined the appropriate ranges in Step 2, we have now significantly narrowed the choice of hedge ratio ranges for each material currency exposure. Step 3 is to consider various constraints to arrive at a specific statement of currency hedging policy.

A strategic currency hedging policy needs to fully capture not only the portfolio characteristics and currency market realities, as our framework does, it also needs to acknowledge any material constraints as these apply to the specific investor. Investors need to have the resources to implement the policy at an acceptable cost, weighing a number of trade-offs to determine by how much they want to reduce currency risk. Figure 17 outlines some key questions investors should ask as they determine the appropriate hedging policy and how to implement it.

One of the simplest ways to articulate strategic policy is to target a minimum amount of home currency exposure or a range of home currency exposures to maintain over the medium to long term. For our sample UK-based investor, the starting unhedged exposures and the desired hedge ratio ranges determined so far are shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Original Unhedged Currency Exposures and Desired Hedging Ranges Determined Through the Framework

Sample Investor Portfolio

The investor may articulate strategic currency policy as:

- GBP exposure shall be at least [25%] of the portfolio. This minimum shall be reviewed by the [Governing Body] at least annually and concurrently with any review of the Strategic Asset Allocation.

- GBP exposure shall adhere to a range to be specified by the [Governing Body]. The current range is set at [25%–50%] and this shall be reviewed at least annually and concurrently with any review of the Strategic Asset Allocation.

In this example, the overall ranges noted in the policy have been rounded when compared with the output of the framework to avoid giving a false sense of precision. To some, the resulting range of hedge ratios might still be too wide and represent too much residual risk. While acknowledging this, we note that the result is still a substantial improvement over the starting point of a 0%–100% hedge ratio range for any exposure. Moreover, the framework we have proposed provides ample scope for refinement in particular situations. For example, an investor with greater confidence in measuring exposures or estimates of future expected return is free to vary the original 0%–50% and 50%–100% partitions to narrower ranges if desired.

Step 4: Draw Up an Implementation Plan

The final step is to translate the strategic currency policy into a practical implementation plan. The objective is to achieve actual hedge ratios in the desired ranges while minimising cost and complexity. Implementation plans are generally formulated as target hedges for specific currency pairs within certain parts of the portfolio, as this is a simple low-cost solution, but may also relate to a specific asset class when this is simpler to implement. Ongoing monitoring of the consequences of these decisions should also be considered.

For our illustrative UK-based investor, the analysis done in the previous three steps suggests the following implementation plan is acceptable:

- Hedge 100% of fixed income: simplest action to implement given availability of hedged share classes in the underlying funds.

- Hedge 60% of USD, EUR, and JPY exposure in developed equity allocation.

- Hedge 40% of USD exposure in directional and absolute return hedge funds.

As shown in Figure 19, this implementation plan achieves hedge ratios that fit into the determined ranges while also being easy to specify operationally. The resulting exposure to the home currency is 43%. The investor may choose to hire a currency overlay manager to implement the hedges, and the mandate is unambiguously specifiable in the investment management agreement.

Figure 19. Implementation Plan

Sample Investor Portfolio

Notes: Striped boxes indicate no exposure to the currency for that asset class. White boxes indicate exposure where a hedge ratio could have been assigned, but was not for this implementation plan.

Incorporating views on one or more currencies. Often, investors have strong views on one or more currencies and wish to incorporate this into their currency hedging implementation. The hedge ratio ranges developed offer an easy way to do this while also enabling the investor to attribute performance to the active decision to take such a view. The implementation plan can be chosen to tilt the exposure to be at the top or bottom of a particular currency’s recommended hedge ratio range.

For example, using our UK investor, if the investor strongly believes the GBP will strengthen against the USD, the investor can choose to increase the size of the hedge by increasing the hedge ratio on hedge funds to 50% (this will bring the hedge ratio on USD to the maximum recommended 40% across the whole portfolio). Total portfolio implied GBP exposure after hedging would increase to 46%, instead of the 43% envisaged before the investor’s view was taken into account. The 3% increase represents the size of the tactical bet on GBP strength.

As mentioned in the discussion on the expected return on currencies, investors can also incorporate long-term views into the strategic currency policy (rather than purely taking a short-term tactical position as described above). If the investor strongly believes that GBP will strengthen against the USD, the position of USD in the currency characteristics matrix should be shifted to the right as shown in Figure 20.

Again, we emphasise the illustrative nature of this example in applying our framework to help investors determine hedging policy. Investors can make adjustments at each step to better fit their circumstances and portfolio characteristics. Further, the policy should not just be set and forgotten. Like any policy, the currency hedging should be reviewed periodically to determine whether it still meets the investor’s needs. Any significant change in the portfolio or the characteristics of a foreign currency exposure should prompt a review of the investor’s hedging policy as it relates to that currency pair.

Conclusion

Investors’ exposure to foreign currency is likely far greater than they realise, and can in some cases be large enough to swamp other performance drivers. Yet few investors have given appropriate thought to setting strategic hedging policy, and the typical approaches used today have material drawbacks. Our goal was to develop an integrated approach to currency hedging that considers both asset class and underlying currency exposure characteristics in relation to an investor’s home currency, includes behavioural considerations, retains simplicity of policy formulation, and provides a clear path to implementation.

Our framework provides a robust platform for setting currency policy by:

- Being applicable to the broadest set of investors however they may differ in their risk appetite, portfolio structure, home currency characteristics, or governance resources;

- Accommodating the inherent lack of precision in measuring currency exposures and expected returns from currency hedging;

- Considering cost/benefit trade-offs by separating the question of implementation from strategic policy setting; and

- Providing flexibility to tilt the portfolio on a tactical basis, if investors have a strong view on particular currencies.

A clear currency hedging policy and implementation plan can forestall many of the issues that investors grapple with on the issue of currencies. As with any strategic asset allocation policy, currency hedging policy should be periodically reviewed to ensure it continues to meet the investor’s needs.

Please download the full report pdf to access Appendixes A–E.

Footnotes