Brazil’s equity valuations, though by no means rich, are out of sync with its political uncertainty and economic distress

- Equity valuations are reasonable but not as cheap as might be expected. Brazilian companies’ earnings are cyclically depressed, and are likely to be materially higher beginning in the next year or so. This expectation of improvement in fundamentals has probably already been incorporated into current valuations.

- While the country’s economy might be close to troughing, many of the Brazil index’s largest holdings are multinational firms exposed to the global consumer and commodity markets. From an equity investment perspective, we see little cause to overweight the country’s public equities.

- Broad emerging markets mandates should have similar long-run valuation tailwinds, without the single-country risk and the volatile currency exposure that a Brazil-focused strategy entails.

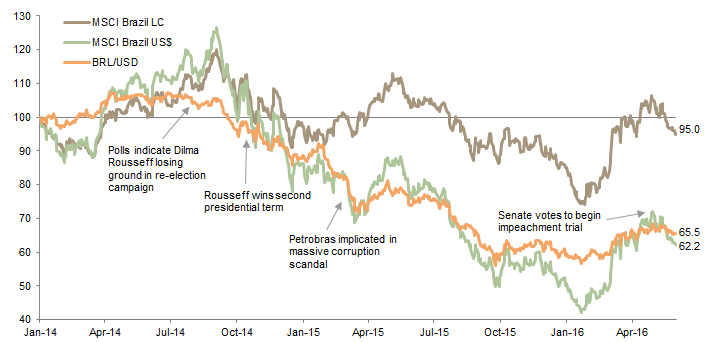

With Brazil at a political crossroads and in deep economic distress, investors are assessing the prospects for Brazilian equities. Even as the country is mired in a recession and lashed by inflation, a grand-scale corruption investigation, and a presidential impeachment process (echoes of mid-1970s US history?), investors are collectively quite positive, with the MSCI Brazil Index about 28% above January’s lows in local currency terms and 48% above in US dollar terms (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative Wealth of Brazil Equities and USD Exchange Rate

January 1, 2014 – May 31, 2016 • Rebased to 100 on January 1, 2014

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any implied or express warranties.

Note: All data are daily.

Is the May departure of President Dilma Rousseff an all-clear for investors to overweight Brazilian equities? In short, no.

Please see Sean McLaughlin et al., “Brazil’s Election is Weeks Away, But Investors Have Already Voted,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, September 18, 2014.

In the run-up to the 2014 election, we worried that investors were overly optimistic about the prospects of a post-Rousseff Brazil; today, we believe investors are once again overestimating the scope of positive change that new interim president Michel Temer could unleash. While public equity valuations in Brazil remain reasonable, and there is scope for near-term economic stabilization, better public market bargains can be had elsewhere. This note aims to answer three questions:

- Why have Brazil’s economy and political environment deteriorated?

- Can the country avoid a debt crisis and reinvigorate growth?

- What are the implications for investors?

Why Have Brazil’s Economy and Political Environment Deteriorated?

To answer this first question, let’s go back to that 2014 election. In late summer 2014, it seemed the presidency was slipping away from Dilma Rousseff, the successor to popular president Lula De Silva. Momentum appeared to be in the hands of Rousseff’s election challengers, but she surprised investors by pulling off a victory. However, the victory celebration was not a long one. Pressured by falling commodity prices and shrinking Chinese demand for raw materials, the Brazilian economy began to contract. From 2014 through the end of this year, the cumulative contraction may near 10% according to some estimates.

At the same time, the “Carwash” corruption scandal, involving state-controlled but publicly listed oil giant Petrobras, pushed onto the front pages of newspapers. This scandal featured bribery and kickbacks from Petrobras contractors on a grand scale. More than 170 people have been charged with offenses, with Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) closely linked to the corruption. Estimates of the total hit to the state from the corruption vary from BRL29 billion to BRL42 billion—roughly 1% of GDP!forward to May 2016, and a deeply unpopular Rousseff has now been suspended due to impeachment proceedings, replaced by her vice president Michel Temer. Ironically, the impeachment charges are not related to the Carwash scandal, but rather to misrepresenting the state of the country’s finances.

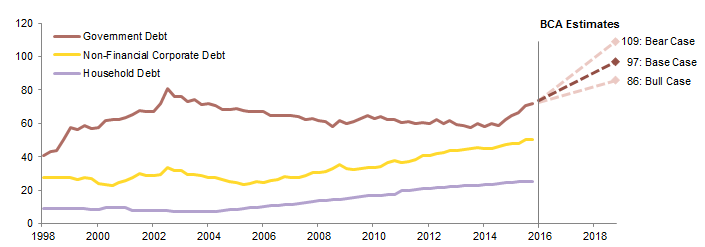

And those finances are looking ugly, the consequence of both the commodity bust and unsustainable government policies. For a second straight year, the budget deficit for 2016 is close to 2% of GDP before interest payments on debt amounting to roughly 10% of GDP. Public debt at year-end amounted to 72% of GDP, and the base case from economic research firm BCA Research assumes that will grow to 97% of GDP in 2018 (Figure 2).[1]Please see Santiago Gomez et al., “Brazil: Impeachment Is No Panacea,” BCA Research, April 26, 2016. Given double-digit interest rates on public debt, the new government needs to turn the ship quickly before it rams into an iceberg of debt.

Sources: Bank for International Settlements, BCA Research Inc., and Institute of International Finance.

Notes: Data are quarterly. Debt as percent of GDP values for Q4 2015 are an IIF estimate. After 2015, data are estimates from BCA.

This task requires a level of austerity that would be unpalatable to many in a strong economy, but unfortunately Brazil’s economy today is quite weak. Real GDP contracted by 3.7% last year, and the median forecast pencils in a slightly larger drop for 2016, implying a cumulative economic decline of 7.6%. A Reuters poll of economists in February suggested that the economy would not recover to its pre-crisis level until 2019. Unemployment has spiked from 6.2% to over 10% and continues to rise, as jobs disappear at the rate of about 100,000 per month.

Can Brazil Avoid a Debt Crisis and Reinvigorate Growth?

Into this treacherous terrain steps unpopular interim president Michel Temer and his very popular new finance minister Henrique Meirelles, who must decrease government spending, increase tax revenue, or both, at a time when consumers and businesses are already in the trauma bay. Temer and Meirelles will likely try to reform the government-provided pension system (the average retirement age is just 54, and next year’s expected pension deficit is US$63 billion), which won’t lower the budget deficit but might buy them some time with investors. Temer has also pledged to reform the tax code, shrink the country’s unwieldy and expensive government bureaucracy, and provide employers with more labor flexibility (which might be a tough sell politically, given Brazil’s dismal unemployment situation, even with today’s employee-friendly rules).

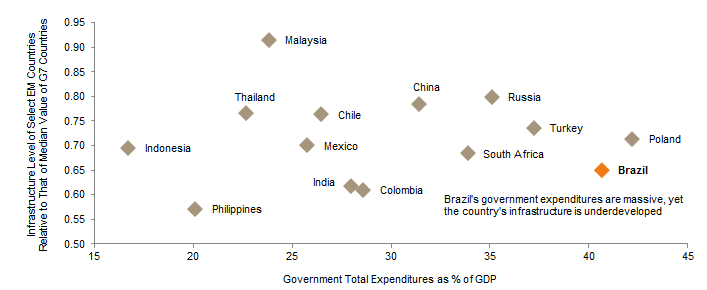

Temer and Meirelles are also likely recognize that the country’s poor infrastructure limits both growth and the investment appetite of foreign multinationals, and they may look to expand the private sector’s role in producing energy and operating the country’s infrastructure. The Brazilian government receives vastly more in tax revenue than most emerging markets peers (government spending is an astonishing 41% of GDP), but with precious little to show for it (the World Economic Forum rates the country’s infrastructure at just 65% the level of developed markets countries, compared to 75%–80% ratios for Chile, China, Mexico, Russia, and Thailand, all countries where the “market share” of government within the economy is much smaller than in Brazil). Additionally, of the 14 countries shown in Figure 3, Brazil is one of only three whose infrastructure rating has deteriorated over the past five years.

Figure 3. Infrastructure Development Compared to Government Spending: Brazil and Other Emerging Markets

As of April 30, 2016

Sources: International Monetary Fund – World Economic Outlook Database and World Economic Forum: The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–2011 and The Global Competitiveness Report 2015–2016.

Note: Y-axis represents the ratio of 2015–16 infrastructure score for select EM countries and that of median value of G7 countries.

Temer has an imposing task. Will he be able to get it done? We have concerns. His agenda would be politically challenging during a deep recession, even for a politician elected in a landslide. Temer, on the other hand, is only moderately less unpopular than his predecessor (a mere 8% of polled Brazilians think he will do better than Rousseff), and has somewhat of a lame-duck role (Rousseff is barred for at least 180 days; a general election is unlikely until late 2018).[2]Temer also has corruption taints of his own, with the electoral authority investigating whether Carwash bribes helped fund the 2014 Rousseff/Temer election campaign. We believe that these allegations … Continue reading

On the other hand, perhaps Temer will get some assistance from the economy itself. Tentative indications are that the Brazilian economy may be bottoming. Additionally, inflation has fallen and the real has stabilized enough that Temer is likely to lower the policy interest rate from its nosebleed 14.25% level, helping to at least loosen the reins a bit on the country’s businesses and consumers.

The task for Temer is formidable, which is not to say completely impossible.

What Does This Mean for Investors?

While the new president has little room for error, investors have certainly been rallying behind him. The currency has rallied furiously, alongside asset prices. Yields of dollar and local currency government bonds have contracted by 141 bps and 309 bps, respectively, from the end of 2015 to May 31 of this year (Figure 4). Spreads remain elevated relative to historical levels, but have also moderated (particularly for government bonds).

Figure 4. Bond Yields and Option-Adjusted Spreads in Brazil

December 31, 2003 – May 31, 2016 • Percent (%)

Source: Barclays.

Notes: All data are monthly. LC government bonds, USD corporate bonds, and USD sovereign bonds are represented by Barclays EM Local Currency Government: Brazil; Barclays EM USD Corp: Brazil; and Barclays EM USD Sovereign: Brazil, respectively. Barclays EM Local Currency Government: Brazil starts July 2008.

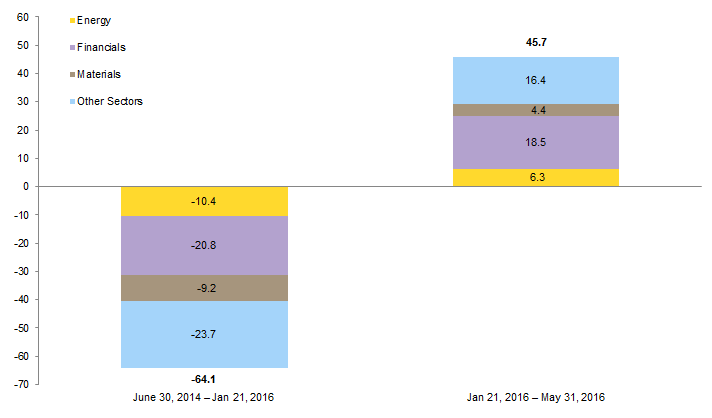

As bond spreads have tightened, equity prices have rallied as well. From the middle of 2014 (roughly when oil prices came under pressure) to this January, the MSCI Brazil Index fell 64% in US$ terms, and since then it has rebounded nearly 50%.[3]Because the recent percentage increase is off a smaller base than the percentage decline, prices remain 41% below their pre-crash levels in US$ terms; they are also 82% below the all-time highs of … Continue reading The country’s energy and materials sectors led the way down, as well as the way back up (Figure 5).

Sources: FactSet Research Systems and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any implied or express warranties.

Notes: Price return data are based on daily price level data. Other sectors include consumer discretionary, consumer staples, health care, IT, industrials, telecommunication services, and utilities.

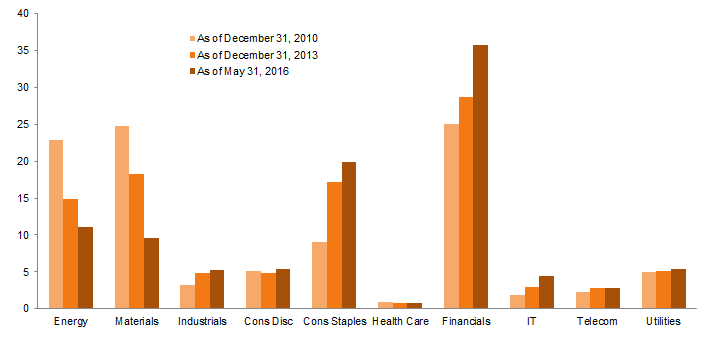

It is difficult to say how equities will respond if the country’s economy stabilizes and rebounds. A growth rebound would likely boost earnings for the large financial sector, which is well above one-third of the index. The consumer staples sector is nearly 20% of the index, but is not particularly geared to Brazilian consumers—55% of the category by market cap is one company, global brewer AB InBev (Budweiser, Beck’s, Corona). Even if the Brazil index were composed mainly of companies selling goods and services to Brazilians, we would be skeptical that the pace of domestic economic growth would be strongly tied to the level of equity returns—after all, it rarely is. However, it is possible that trading of Brazilian stocks will in coming quarters be less tied to commodity prices—the index is considerably less concentrated in commodity producers than it was in 2010: about 20% total in energy and materials stocks, compared to 48% total in 2010 (Figure 6). Earnings have been cyclically devastated and will probably rebound. At least they had better, or investor disappointment will be palpable: the analyst consensus calls for a 68% increase in per-share earnings for the MSCI Brazil Index in 2016 over 2015.

Sources: FactSet Research Systems and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any implied or express warranties.

What will influence equity returns? Reiterating this may be a causa perdida (lost cause) during this period where valuations don’t seem in a hurry to revert, we nevertheless believe valuations are a key driver in subsequent returns. And valuations of Brazilian equities strike us as reasonable, but not particularly cheap. Stocks are trading at 10.9 times ROE-adjusted earnings, moderately below the long-term median for the Brazilian market (Figure 7). On a relative basis, Brazil trades at a 6% discount to the broad emerging markets index, less than the historical median discount of 12%. That said, the historical median for the Brazil market is fairly low, and that median is influenced by the low valuations coming out of the hyperinflationary 1990s. If we only had 15 years of data rather than 20 years, Brazilian stocks would look considerably cheaper relative to their history. Further, dividend yields are a chunky 4.0%, well above the 2.9% yield of the broad emerging markets index.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any implied or express warranties.

Notes: Graphs based on monthly data. CPI data are as of April 30, 2016.

While listed equity markets offer reasonable valuations, there appear to be more compelling valuations in other emerging markets countries and regions with lower currency volatility and with greater economic and political stability. And the sector mix of the country’s equity market does not appear to be closely linked to domestic economic growth.

A Single-Country Overweight to Brazil Still Not Our Cup of Tea. Given that Brazil’s situation has only very tenuously improved, with significant scope for disappoint, and that valuations are not particularly cheap, we would be cautious about establishing an overweight position in Brazilian equities. Such a position would have been enormously rewarding over the past five months (with the right entry timing), but investors can’t secure this recent outperformance by buying aggressively into Brazil’s continued run-up. Investors buying emerging markets equities broadly can benefit from valuations that, at least on our preferred metrics, appear cheaper than those in Brazil, and where investor expectations for macroeconomic improvement appear to be less demanding.

That said, many investors use active emerging markets managers, and investors in these funds may want to make sure they understand their exposure to Brazil and how it may have changed over time. We examined 168 global emerging markets funds for which we had country exposure information and found that one quarter, or 42 funds, had changed their relative exposure to Brazil over the course of 2015 (Figure 8).[4]Of the 75% of managers that did not change their posture, the managers that were consistently overweight had a lower median return over 2015 and the first quarter of 2016 (-10.7% cumulative) compared … Continue reading Half of these had perhaps tried to cut their losses, moving from an overweight position at the end of 2014 to an underweight position at the end of 2015.[5]Weightings and performance as discussed here solely refer to the manager’s posture relative to peers, rather than relative to a passive index. For managers that reported gross instead of net … Continue reading This was not helpful from a performance perspective: this group had the lowest median return for the full period of 2015 plus the first quarter of 2016 (-10.8% cumulative). The other half took the opposite tack—they started out under-allocated to Brazil at the end of 2014 compared to peers, and then rotated in (perhaps attracted by valuations): median cumulative returns for this group were somewhat better at -9.9%.

Figure 8. Brazil Exposure Trends for Global Emerging Markets Managers

2014 vs 2015 Exposure and Returns From First Quarter 2015 – First Quarter 2016

Source: Cambridge Associates.

Notes: Percentages sum to more than 100% due to rounding. Overweight or underweight refers to the manager’s Brazil equity exposure relative to the median exposure of the 168 funds examined as of December 31, 2014, and December 31, 2015. Median manager exposure was similar to the index weighting for Brazil in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Median manager exposure to Brazil at the end of 2014 was 8.8% compared to 8.9% for the MSCI EM Index, and 5.3% at the end of 2015 compared to 5.5% for the index. Median returns are quarterly reported returns from first quarter 2015 through first quarter 2016. For managers that reported gross instead of net returns, net returns are estimated by subtracting 1% per year of assumed fees and expenses from the manager’s reported gross return.

Following on this analysis, investors in a fund that moved from overweight at the end of 2014 to underweight at the end of 2015 (after relative valuations had improved markedly) should make sure they understand what was behind the change in allocation. There are many legitimate reasons for this behavior (a top-down call on the country, a momentum indicator, deteriorating fundamentals, concerns about currency volatility and inability to hedge it, or bottom-up decisions on individual stocks). The key is for investors to determine whether the manager’s action is consistent with its stated strategy and historical modus operandi, and, in the case of a top-down call, whether the manager has the resources and expertise to make those calls effectively.

While we do not advise investors to tactically overweight Brazil, they should refrain from neutralizing any overweights employed by their global emerging markets managers. This sounds like a contradiction, but remember that active managers are unlikely to overweight Brazil by owning exposure identical to that in the MSCI Brazil Index. Their Brazil holdings may look substantially different than those of the cap-weighted index, and their overweight may be based on bottom-up analysis of those specific stocks, rather than premised on the continuation of the Rousseff impeachment rally. And to be clear, it is possible that the MSCI Brazil Index will continue to outperform as it has this year—we simply believe there is not, at this point, a good case to be made for that.

Private Equity Opportunities Are Worth a Look. For investors that believe Brazil’s economic growth will rebound soon, private equity markets may offer intriguing opportunities. Asset valuations seem attractive, lending to middle-market companies is constrained, and exposure to the domestic economy appears to be more direct. Sectors including health care, education, IT, logistics, and agribusiness could see growth, even as the country’s overall economy has been contracting. Additionally, Temer has spoken of privatization plans for utility assets and other government property, and private equity infrastructure managers will likely be evaluating the quality and price of these assets, as well as the ability of future owners to operate the assets profitably. Private market investors, of course, face illiquidity risk and uncertain timing of cash flows, which makes hedging currency risk next to impossible (though, practically speaking, few public markets investors hedge the Brazilian currency either). We are actively assessing private opportunities.

Concluding Thoughts

In the wake of the impeachment proceedings against President Dilma Rousseff, as well as the massive bounce in Brazilian equities this year, many investors are re-assessing the prospects of the country and its equities. If interim president Temer and his cabinet are successful in accomplishing their stated goals, the economy would get a needed boost. However, there is substantial uncertainty about whether the goals are achievable, and significant risk if the situation does not improve quickly.

With the country’s economy potentially close to turning around, is this a buying opportunity for investors? Unfortunately, we don’t believe so. Equity valuations are reasonable but not as cheap as emerging markets broadly, and the Brazil index’s sector weights are not particularly aligned with domestic economic growth. Private equity markets may be better positioned to benefit from a rebound. Investors should refrain from single-country overweights to Brazil’s listed equity markets, and they may wish to examine how their emerging markets managers’ positioning has evolved during the country’s economic crisis.

Sean McLaughlin, Managing Director

Nroop Bhavsar, Senior Investrment Associate

Footnotes