While cap-weighted benchmarks for bond portfolios remain the norm, indexes based on other criteria are increasingly available. Benchmarks are an essential tool for investors to monitor and analyze overall portfolio performance, as well as the success of investment strategies and managers. Comparing manager performance against benchmarks also can help inform decisions about whether to use active or passive managers. So while most investors are naturally (and properly) interested first and foremost in whether portfolio returns meet or exceed their goals, periodically reassessing whether current benchmarks remain appropriate yardsticks is important.

This paper reviews this trend toward alternative indexes and compares them to traditional benchmarks. We conclude that while it is premature to abandon benchmarking against cap-weighted indexes, alternative bond indexes are a promising development to monitor. These indexes may be appropriate benchmarks for certain discrete portfolio bets, and could be helpful for tracking performance (in conjunction with traditional cap-weighted benchmarks) where managers have systematic tilts against the traditional benchmark.

Creating Fixed Income Indexes

At roughly $90 trillion,[1]Per the Bank of International Settlements (March 2013), this figure represents fixed income of “all maturities, amounts outstanding . . . the fixed income universe (which includes a substantial amount of very short-term debt) is much larger than its equity counterpart. It is also far more differentiated, comprising a broad range of instruments that vary not only by geographical market, size, and industry (the major differentiators for equities) but also by issuer type (public or private), credit quality, maturity, yield, and rate type (fixed or floating). This variety means that fixed income instruments can assume more roles in a portfolio—deflation or inflation hedge, source of income or liquidity, diversifier, growth play—than can equities, and underscores the importance of selecting appropriate benchmarks.

Creating and maintaining an index is more complex for fixed income than for equities. More than 1.1 million individual municipal bonds and around 40,000 US corporate bonds were outstanding in 2012, compared with less than 4,500 stocks listed in the United States.[2]Rachel Louise Ensign, “Quirks of Bond Indexing,” The Wall Street Journal, July 9, 2012. A manager is unlikely to be able to buy most, let alone all, of the securities in the market. Moreover, because fixed income is generally traded over the counter rather than on an exchange, pricing is often less than straightforward. The changing characteristics over time and eventual maturity of bonds present additional complexity.

Index providers address these construction issues through replication—focusing on key characteristics of the relevant fixed income universe such as the yield curve—and the extensive use of derivatives. The most widely accepted methodology for creating indexes is to weight constituents by their market capitalization. Such indexes appear to represent the investable market, are easily understandable, and reflect price movements and other changes in the market such as issuance, maturity, or default. Table 1 sets out the key characteristics of several well-known bond indexes, all of which are market cap weighted.

Sources: Barclays, Citigroup Global Markets, and J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc.

Notes: The above indexes are weighted on the basis of market capitalization. The Barclays Global Treasury Index is a sub-index of the Barclays Global Aggregate Index and therefore has the same index inclusion criteria. The minimum maturity for the above indexes is one year, apart from the J.P. Morgan Government Bond Index Emerging Markets Broad, which has a minimum maturity of 13 months. J.P. Morgan regulates minimum issue size through liquidity requirements and therefore does not have minimum issue sizes.

Flaws in Market Cap–Weighted Benchmarks

While market cap–weighted indexes are investable, fully accepted in the marketplace, and provide broad market coverage, they have certain inherent flaws when used as benchmarks. These flaws are particularly evident in the case of sovereign bonds. Figure 1 shows US institutional client exposure to all fixed income. While we include total fixed income exposure for purposes of reference, sovereign bonds constitute by far the greatest portion of this exposure. Most of the following discussion focuses on sovereign bonds.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Allocation data shown for all institutional (non-taxable) clients. Global ex US emerging markets bonds data begin in 1997. The “n” in the horizontal axis label shows the count of clients represented in each year’s allocation data.

The cap-weighted methodology ensures increased exposure to index constituents that have done well relative to other constituents—something like a buy high/sell low strategy. While most remarked upon in the equity space, it’s perhaps more important in the case of fixed income given the defensive role for which this asset class, certainly its sovereign bond component, is generally used.

For example, a country’s (or company’s) issuance of more bonds than other countries/companies increases its index weight. Such issuance may reflect strength—high market confidence in a growing economy (firm) that wishes to fund infrastructure (cap ex). However, in other instances it may stem from “weakness”—a large budget deficit in the case of a sovereign or poor cash flow or a weak balance sheet in the case of a company.

Other factors may also affect sovereign bond prices, changing index weightings in ways not necessarily consonant with the higher index representation of “stronger” countries (as reflected by higher market capitalization). For example, a country might need to issue debt to fund large fiscal deficits, or a central bank might lower interest rates to boost a slowing economy or buy domestic bonds under a program of quantitative easing to keep market yields down. As a result, investors in the index (assuming it is global or regional rather than country-specific[3]This is not an issue for corporate bond indexes as investors would not be buying/benchmarking against the debt of a single company.) will arguably be buying countries high (i.e., when they are less solvent, their economies are weakening, or their bond prices are artificially supported) and selling them low. In addition, to the extent that the debt of less creditworthy issuers becomes a larger percentage of the benchmark, investors holding products managed against such benchmarks can potentially run afoul of credit quality investment criteria.

In 2011 alone, Standard & Poor’s downgraded debt issued by the United States, Japan, Italy, Spain, and other developed countries, which collectively represented more than two-thirds of the Citigroup World Government Bond Index (WGBI).[4]From a longer-term perspective, whereas most advanced economies had AAA-rated government debt during the 1990s, this percentage had fallen to about two-thirds by the end of 2007 and about half by … Continue reading The index’s credit quality today is AA compared with AA+ before the financial crisis, with a significantly lower coupon (2.6% versus 3.8%) and yield to worst (1.6% versus 3.3%) and higher modified duration (6.6 years versus 6.1 years) (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the share of US debt within the Citigroup WGBI has increased to 29% from 20%, even as the US credit rating has declined. The rise in US index weighting has essentially come at the expense of Europe, which now has a 40% weight, compared with 49% six years ago. Similarly, US Treasuries and Agencies accounted for 32% of the Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index at the end of 2007, but almost 40% of the index six years later thanks to the issuance of massive amounts of Treasuries and Agency bonds in connection with the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing program.[5]By contrast, changes in the composition of the Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index over this period were minimal. However, the expected effect of massive US government bond issuance led Barclays to … Continue reading

Sources: Barclays, Citigroup Global Markets, and J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc.

Notes: The other developed markets category consists of Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, and Singapore. EM debt uses the J.P. Morgan GBI EM Broad Index.

Cap-weighted indexes may thus represent (or come to represent) a series of exposures different from what the investor is looking for (or assumes is present) in its fixed income allocation. In particular, for sovereign debt allocations intended to support spending in a stressed environment, managing (and therefore benchmarking) against the cap-weighted index may be riskier than the investor realizes. For example, even if a higher yield (resulting from the sovereign raising rates to attract investors) theoretically compensates the investor from a risk/return perspective, the index choice will still be inconsistent with the investment purpose. More generally, the risk/return profile of any sovereign bond may be skewed if the country’s central bank has purchased (or is purchasing) substantial portions of domestic sovereign debt and kept such debt on its balance sheet, as this artificially depresses rates.

Benchmarks are most commonly indexes, but it is important to recognize that the two are not necessarily the same. Indexes were created first and are intended to represent the market activity of an asset class or subset thereof. Benchmarks, however, are intended to represent an investable universe; they are also supposed to be consistent with an investor’s desired exposure. As we wrote in our 2013 report From Asset Allocation to Risk Allocation: The Risk Allocation Framework, “benchmarking is most effective when the performance being evaluated is relative to a specific, well-defined mandate that is both objectively representative of the opportunity set and passively investable.” Therefore, while the S&P 500 Index is both an index and a benchmark, the S&P/Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price Index is an index but not a benchmark, as it is not really investable.

Finally, market cap–weighted indexes may simply not capture what an investor’s bond managers are doing and therefore be inappropriate for measurement purposes. If a sovereign bond manager systematically underweights one country’s low-yielding bonds in favor of another country’s higher-yielding bonds, or plays in the credit space, the manager may outperform a cap-weighted benchmark in a risk-on environment. However, the manager’s exposure may well be a mismatch with the investor’s needs, unexpectedly damaging the portfolio in the event of a flight to safety.

Investors should know if their managers are systematically tilting to portfolios that are riskier than the indexes to which they are benchmarked. Even if investors are comfortable with such strategies, they should benchmark in such cases against both an index reflecting the desired exposure and, if there is a difference, an index that better represents each manager’s actual strategy. As discussed in the next section, this may well be an alternative index. Likewise, since manager biases can obscure performance, analytic measures such as tracking error and information ratios are useful.

Overview of Alternative Bond Indexes

In a survey published in February 2012, 37% of respondents said they were “concerned” or “very concerned” about the biases in standard indexes. With respect to fixed income, the concern revolved around “biases toward [issuers with] larger debt issuance.”[6]Northern Trust, “Customised Beta: Changing Perspectives on Passive Investing,” Line of Sight (Asian Edition), February 2012. This sentiment, together with the low yields currently offered by the bonds represented in traditional fixed income indexes, a decline in credit quality, and investors’ efforts to lower the costs associated with active managers, helps explain the growing popularity of alternative bond indexes.

While we use the ore neutral term “alternative” here to describe these indexes (or strategies), they are often labeled “smart beta” since they represent efforts to replicate at a lower cost manager methodologies that have outperformed traditional indexes or better captured exposure to the market.[7]Other terms used in the marketplace to describe these indexes include advanced beta, beta plus, engineered beta, fundamental indexing, intelligent beta, new beta, research-enhanced indexing, and … Continue reading The idea behind alternative bond indexes is not new—investors tried, for example, to limit Japanese bond holdings (and benchmark accordingly) in the mid-1990s after the bursting of the Japanese bubble. However, concern about cap-weighted indexes is more widespread today.

Construction Methodologies

Alternative sovereign bond indexes come in different flavors but are essentially based upon GDP, country (or company) fundamentals, or a combination of the two. We briefly summarize the basic approaches, and their advantages and disadvantages, in this section. Table 2 provides more detailed information on the methodologies used to create several of these indexes.

Table 2. Alternative Bond Indexes: Methodologies and Other Key Characteristics

As of December 31, 2013

Table 2. Alternative Bond Indexes: Methodologies and Other Key Characteristics (continued)

As of December 31, 2013

Sources: Barclays, BlackRock, Citigroup Global Markets, Goldman, Sachs & Co., and PIMCO.

Note: The minimum maturity for the above indexes is one year, apart from the BlackRock Sovereign Risk Index, which is not investable. Minimum issue size not available in US$ equivalent for Citi RAFI Sovereign Emerging Markets Local Currency Bond Index Master.

The most commonly used alternative sovereign bond index methodology is to weight on the basis of GDP. This results in greater geographical diversification than market-cap weighting because world GDP is less concentrated than the global bond (or equity) market (Figure 3). For example, Japanese Government Bonds account for just 9% of the Barclays Global Treasury Universal GDP-Weighted Index compared with 27% of the Barclays Global Treasury Index. The percentage of US Treasury bonds, however, stays roughly the same (about a quarter of the total in both cases). In addition, in the case of sovereigns, GDP weighting presently favors less indebted countries given the current makeup of the global sovereign bond market.

Sources: Barclays, Citigroup Global Markets, International Monetary Fund – World Economic Outlook Database, and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Global equities represented by the MSCI All Country World Index. Global fixed income represented by the Barclays Global Multiverse Index, which includes global investment-grade and high-yield debt. Global sovereign bonds represented by the Citigroup World Government Bond Index.

Even so, GDP weighting does not result in an index that fully mirrors the global economy since the size and liquidity differentials between sovereign (and corporate) debt markets is greater than differences in GDP. China accounts for 6.8% of the Barclays Global Treasury Universal GDP-Weighted Index, roughly three-fifths of its 11% share of global GDP. At least one provider argues that GDP weighting is also countercyclical since it allows scope for higher weightings of countries in the expansion phase of the business cycle (when bond prices are often falling) than would be the case if the index was cap weighted.

Other alternative bond indexes look at a range of fundamental measures. For sovereign bonds, such indexes basically fall into two categories: supplementing GDP weights with measures such as population or budget metrics, or primarily focusing on countries’ financial health and credit quality.[8]With respect to corporations, index providers look at various financial statement metrics or credit volatility. The Goldman Sachs Global Sovereign Debt Sustainability Index is an example of the former, while the BlackRock Sovereign Risk Index (a credit-risk metric rather than a bond index) is an example of the latter (Table 2). Fundamental indexes potentially can also cap exposure to any particular country or market or follow other rule-based approaches. Figures 4 and 5 compare several cap-weighted and alternative bond indexes on the basis of various metrics.

Sources: Barclays, Citigroup Global Markets, Goldman, Sachs & Co, J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and PIMCO.

Figure 5. Comparing Maturity, Duration, and Yield for Traditional and Alternative Bond Indexes

As of December 31, 2013

Sources: Barclays, Citigroup Global Markets, Goldman, Sachs & Co, J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and PIMCO.

Note: The Citigroup WBIG index shows maturities 10–20 years for the graph segment labeled 10–15 years, and 20+ years for the graph segment labeled 15+ years.

Building a customized bond benchmark is another possibility, although the cost makes this more feasible for investors that can spread it across a larger asset base. A customized benchmark is sometimes referred to as an “actively designed, passively managed” approach that proponents would characterize as a way of capturing mechanical alpha or turning alpha into low-cost beta. Even with their additional construction and management costs, customized bond benchmarks could still be a cheaper option than active management.

Alternative bond indexes offer investors the potential to diversify exposure, lower certain risks associated with cap weighting, and tailor their portfolios toward desired exposures with respect to credit quality, duration, geography, etc. They can help investors align investment opportunity sets with the purpose of their fixed income portfolios, which is particularly important for sovereign bond allocations given their role within the portfolio. Using alternative indexes may also lower investors’ costs and make them better able to benchmark manager performance.

Biases

Alternative indexes have their own stylistic biases or, to put it another way, their own idiosyncratic risks. As with cap weighting, such risks reflect their construction methodologies. For example, a GDP-weighted benchmark may entail high (relative to market cap) exposure to countries or companies whose bonds have relatively low liquidity or are of low credit quality.[9]Of course, the conclusion that the indexes have lower quality bonds on the whole is true only if one accepts the ratings agencies’ views, something that providers of fundamental indexes implicitly … Continue reading

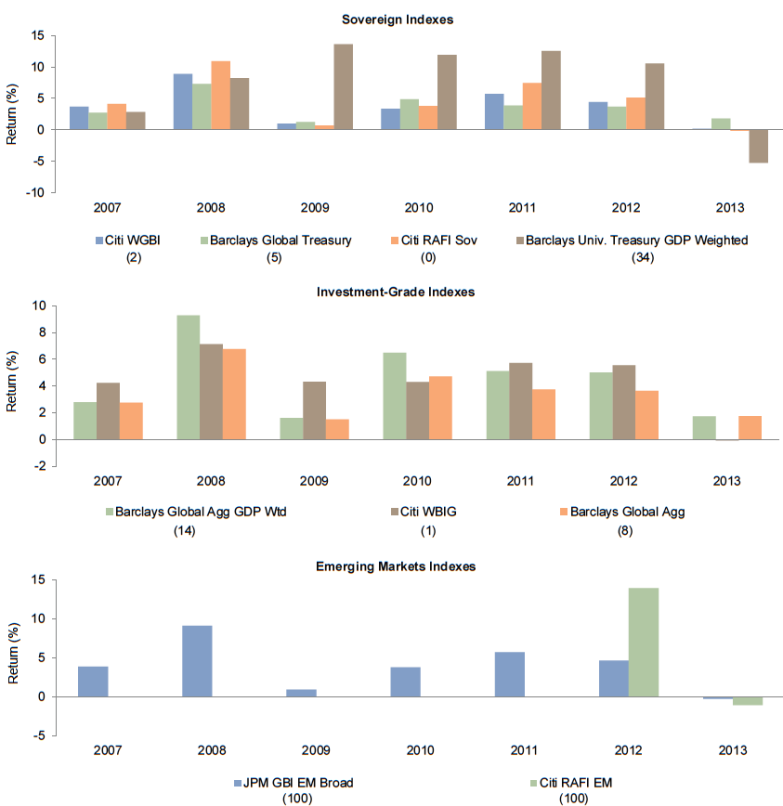

The merits of using a GDP-weighted bond index to benchmark sovereign bonds held to support spending in a stressed environment are not at all clear. The experience of 2008 provides a dramatic illustration: the Pimco Global Advantage Government Bond Index—incepted in 2010, with performance backfilled to 2003—would have returned 4.5% in US$ terms and sharply underperformed the Citigroup WGBI and Barclays Global Treasury Bond Index, both of which returned more than 10% (Figure 6).[10]The Barclays Global Aggregate GDP Weighted Index would have returned 2.6% in unhedged US$ terms in 2008, well below the Barclays Global Agg’s 4.8% return, although the alternative index … Continue reading This would have been problematic for investors seeking support for spending in the wake of the MSCI World Index’s -40.7% return (-38.7% in local currency terms).

Figure 6. Annual Returns for Traditional and Alternative Bond Indexes (continued)

2008–13 • Local Currency

Sources: Barclays, Bloomberg L.P., Citigroup Global Markets, Goldman, Sachs & Co, J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and PIMCO.

Notes: Data for the Goldman Sachs Global Sovereign Debt Sustainability Index begin January 1, 2009. Data for the Citi RAFI Emerging Markets Index begin November 2011. Figure in parentheses below index name refers to percent of emerging markets exposure as of December 31, 2013. Local currency returns are not available for the PIMCO GLADI Government Bond Index, the PIMCO GLADI Index, or the Goldman Sachs Global Sovereign Debt Sustainability Index.

Likewise, the global financial crisis would have presented a difficult test for the Citi RAFI Sovereign Debt Developed Markets Bond Index, which is based on fundamentals. In 2008 the index—incepted in 2012, with performance backfilled to 2001—outperformed the cap-weighted indexes handily in local currency terms. However, the return to unhedged US investors would have been only 5%, 500+ bps less than the return of the cap-weighted indexes (Figure 6). Therefore, even though the theory behind “fundamentally weighted” bond indexes is that they will underperform in risk-on environments given their focus on fiscal strength, but outperform in risk-off environments and over the long term, investors need to look closely at the methodology rather than just the description, and consider variables such as currency.

These examples indicate the importance of understanding exactly how the new indexes and products/managers benchmarked against them work and how they should perform in different economic environments, including a financial crisis. If the indexed bonds would not have offered better protection in 2008 than a product tracking the cap-weighted benchmark index, for example, investors need an answer as to whether (and why) they should expect better performance the next time around.

Alternative bond indexes that focus on issuers’ financial soundness, assuming they function properly, will almost certainly help mitigate the risk of an issuer default. No large developed country has defaulted in recent years, but this is certainly a significant risk. To the extent that issuers’ weights in traditional indexes significantly exceed their share of the global economy, the more diversified GDP-weighted index will mitigate losses in the event of an issuer default. Likewise, index caps on exposure to individual sovereigns or corporates potentially can provide some downside protection.

As for duration risk, if an alternative bond index has lower duration than a cap-weighted one, it will underperform in a bull market but outperform in a bear market. But there is no inherent reason to think that alternative bond indexes will necessarily have lower duration. At present, the alternative developed markets index durations and average maturities are slightly lower—and the yields higher—than those of their cap-weighted counterparts, but the picture is more mixed in the case of alternative emerging markets and broader investment-grade indexes (Figure 5).

In summary, benchmarking a bond allocation against an alternative index presents its own set of issues and requires investors to be actively engaged. Within the alternative bond index universe, the use of alternative indexes applying at least some fundamentals related to countries’ (companies’) fiscal health may well make more sense for investors relying on such bonds to cover their spending needs in a stressed environment than indexes based solely on other fundamentals or on GDP. Even so, the choice of metrics to measure fiscal health, etc., is inherently subjective and therefore likely to be flawed to some degree. For example, Blackrock’s Sovereign Risk Index (which is not presently investable) rated Italian debt in January as riskier than that of both Nigeria and Ukraine, a result with which some investors might not be comfortable. More broadly, how should one evaluate one country with a 4% budget deficit versus another with a 5% deficit? At what point is a debt/GDP ratio dangerously high, signalling the potential for a sharp rise in borrowing costs, meaning losses for investors? It is impossible to say for sure, especially as Japan, despite having long had the developed world’s highest (and increasing) debt/GDP ratio, has not seen the yield on its ten-year government bond exceed 2% since 1999.

Which Benchmark to Choose?

As with any asset class or investment strategy, investors should choose a benchmark that is consistent with the purpose of their fixed income allocation and, similarly, evaluate managers (or passive investment products) on that basis—against benchmarks that actually represent the universe of their strategy. Although alternative indexes conceptually may capture bond investors’ intended exposure more accurately, in practice market cap–weighted indexes can still turn out to be the more appropriate tool. Again, we go back to 2008, when a high concentration in US and Japanese sovereign bonds helped protect investors much more than did an allocation to a more diversified index.

Investors looking at alternative bond indexes should therefore consider carefully their inherent biases and look closely at how they perform. A decision to use such an index requires careful monitoring of any significant changes in its composition. Northern Trust has noted the following issues raised by alternative indexes: tracking error versus traditional indexes, higher turnover, higher licensing costs compared with passive indexes, index risk, cycle factors, lack of a track record, and investment rationale/primary factor.[11]Northern Trust, “The New Active Decision in Beta Management,” Line of Sight, April 2013. With respect to turnover, rebalancing almost certainly will mean higher transaction costs than for a market cap–weighted index fund. In 2013, FINRA issued an investor alert, warning that alternative funds often had limited performance histories and high costs. Finally, should “alternative” indexes become the norm, they will eventually end up looking like market cap–weighted indexes. In other words, overly high take up could make them a victim of their own success.

Another possibility is to use a combination of cap-weighted and alternative bond indexes. The former would be used to reflect broader fixed income strategies while the latter would be employed to align with portfolio positions that reflected strategic or tactical bets or concerns. Thus, an investor could use the PIMCO Global Advantage Bond Index to reflect exposure to a manager (such as PIMCO) lowering bond duration due to concerns about the risk of a rise in interest rates. Combining more than one index to create a benchmark would be consistent with what we have seen from several managers in the emerging markets space that have taken this approach given the many facets of emerging markets debt.

Investor Interest

Are alternative indexes catching on in the fixed income space? In 2011 Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund and a “thought leader,” began weighting its European government bond holdings on the basis of GDP; the following year, it implemented a GDP-weighted benchmark for all of its sovereign debt holdings that also takes into account the fiscal strength of different constituent issuers.[12]Norges Bank Investment Management, “Government Pension Fund Global” (Annual Report 2011). Norges Bank Investment Management, “Government Pension Fund Global” (Annual Report 2012). In 2013, the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) adopted a GDP-weighted index benchmark for its international fixed income holdings.[13]California Public Employees’ Retirement System Statement of Investment Policy for Benchmarks (December 5, 2013) These examples suggest that some of the more sophisticated institutional investors may indeed be leading a move toward alternative bond benchmarks.

In addition, about 17% of respondents to an EDHEC-Risk European Index Survey published in October 2012 said that they used alternative-weighted government bond indexes.[14]Thao Hua, “Institutional Investors Turn to Customized Indexes for Government Bonds,” Pensions & Investments (February 6, 2012). Meanwhile, several of the largest fixed income managers have developed or are developing alternative bond indexes or products for individual clients or the broader public. For example, as of early 2012, about $12 billion of the $60 billion Blackrock managed in passive European fixed income strategies and $48 billion of the $68 billion Northern Trust managed globally in passive fixed income were reportedly benchmarked against customized fixed income indexes.

Looking ahead, institutional investors’ increasing focus on ensuring that asset class allocations perform their intended portfolio roles suggests that there will be increased receptivity to alternative index benchmarks. To date we have seen more interest outside the United States—not surprising given that Treasuries have outperformed international sovereign bonds in every crisis—but this is likely to change as US investors take a more careful look at how best to define and measure their intended exposures. Given that many investors do not view the risk/return profile of sovereign bonds (and fixed income generally) as very appealing given the low yields currently on offer and the potential inflationary risk posed by massive quantitative easing programs, they should be even more interested in ensuring that this defensive piece of their fixed income allocation is properly positioned and benchmarked.

Conclusion

Given the flaws in cap-weighted measures, the rise of alternative bond indexes is a positive development that expands investor options. It accords with a recent survey[15]Northern Trust, “Customised Beta: Changing Perspectives on Passive Investing,” Line of Sight (Asian Edition) (February 2012). finding that investors have shifted their focus to meeting their overall investment objectives rather than simply outperforming a benchmark, and should be viewed as part of the broader ongoing effort across different asset classes to create indexes that better match both the kinds of exposure sought by particular investors and the strategies adopted by particular managers.

While alternative bond indexes are still at a fairly early stage, with a relative dearth of actual (as opposed to backdated) performance history, we view them as an interesting and potentially better way to measure performance and assess managers and investment products. This is particularly true when it comes to developed markets sovereign bonds, which are intended to play a key role in supporting portfolios should equity markets become stressed. Therefore, at the very least, their development of these indexes should be monitored closely.

In theory, both indexes based on fundamentals, which tend to focus on country health, and GDP-weighted indexes, which enhance diversification, should be guideposts that can help investors lower certain risks inherent in fixed income positions. If these indexes better represent the exposure sought by investors, and are investable, transparent, and liquid—and there is no reason to assume they are not—they can be used as benchmarks or at least as reference points to help ensure that the bond portfolio is constructed to meet its objectives and that performance is properly measured. Larger investors less cost constrained (although cost over time should be de minimis) and less concerned about peers will likely have greater interest at this time.

However, until there is greater clarity on how alternative indexes perform, we are certainly not ready to abandon traditional cap-weighted benchmarks. One way to get more familiar with these new indexes is to use them alongside cap-weighted indexes to better understand how they perform in different environments in both absolute and relative terms. Investors might also consider benchmarking satellite managers against appropriate alternative bond indexes even as the bulk of the fixed income portfolio is measured against cap-weighted indexes.

In short, we see no inherent problem with alternative bond indexes and would not discourage their use. However, investors should be clear that, rather than being neutral benchmarks, they represent style bets–just as the decision to stay with a cap-weighted index should be seen as a conscious choice to accept certain risks. Likewise, investors should always keep in mind the context in which these indexes are provided—a highly competitive environment in which index providers and active and passive managers all have their own distinct interests.

Finally, whether these indexes are a way of capturing mechanical alpha or turning alpha into low-cost beta is a second order question that goes to the decision about whether to use active or passive management. If in fact the investor concludes that this is a way to capture alpha inexpensively, such a value proposition might last only until a mass of capital entered the particular strategy, arbitraging away any potential gains.

Contributors

Seth Hurwitz, Managing Director

Lisa Miller, Assistant Manager

Footnotes