In this Edition:

- Are index providers now governance watchdogs?

- After two years in the regulatory hot seat, prime funds’ assets fall and yields rise

- Fintech companies moving from the shadows to the spotlight

- Private funds fee and expense disclosure—still can’t disclose enough?

Multi-Class? Won’t Pass!

Index Providers Want All Shareholders Heard

Who will speak for the common shareholder and take a governance stand against public companies that amass disproportionate voting power in the hands of their founders? In a surprising turn, index providers will! S&P and FTSE Russell have announced plans to prevent some firms that have no or minimal shareholder vote representation from being part of their indexes, while MSCI is currently considering such a step.

S&P announced in late July that companies with multiple share classes will no longer be added to the S&P 500 Index (existing index members will be grandfathered, and the companies will continue to be eligible to enter some other, less popular, S&P indexes). A few days earlier, FTSE Russell stated that Snap Inc. and future IPOs with less than 5% of voting rights in the hands of free-float shareholders will not be index eligible, and that existing index members will be grandfathered in for the next five years, giving them a chance to change their capital structure if they wish to.

Many prominent companies, including Google and Facebook, limit the voting power of public shareholders, giving disproportionate power to founders. The argument for doing so tends to be that the practice allows firms to make long-term decisions and to resist opportunistic hostile takeovers. However, it’s unclear why public shareholders, given voting power equivalent to their ownership percentage, would vote against their own long-term interests, particularly when a large percentage of most companies’ public float is owned by mutual funds rather than individual investors.[1]The growing market share of index funds does not counter this argument. Index fund managers appear to be becoming more activist in recent years. Please see Reshma Kapadia, “Passive Investors Are … Continue reading

While Google and Facebook have clearly delivered strong operational performance since their initial IPOs, to what degree do those sparkling results stem from limits on public shareholder influence? Plenty of other firms with multi-class structures have delivered subpar results for shareholders (in addition to being embraced by technology firms, the structures have long been popular with founders of media companies). Those looking for decisive evidence that firms with multi-class structures perform better or worse than peers will likely come up empty-handed, though a recent study of Brazilian firms found that those with one-share, one-vote structures tended to outperform those with dual-class structures.

The index providers are not the only organizations deciding whether to allow dual-class listings. While stock exchanges in the United States and many other major markets allow them, others, including London and Hong Kong, do not. The latter (after seeing Alibaba list in New York in part because it permitted flotations of firms that did not offer one vote for each share) has proposed a new trading venue for multi-class firms, and the UK regulator has floated a trial balloon about the potential for looser restrictions.

Some governance watchdogs and advocates for institutional managers, however, appear to be throwing their support behind S&P and FTSE Russell. Bjorn Forfang, a managing director at the CFA Institute, wrote in a recent Pensions & Investments op-ed that “…dual-class companies will not be allowed to slip their substandard governance into a widely used market index.” He continued, “Thanks to the actions of S&P and hopefully other index providers, it looks like the price of poor corporate governance just got higher.”

The Great Cash Migration

Forced Retreat from Prime Funds Ups Yields

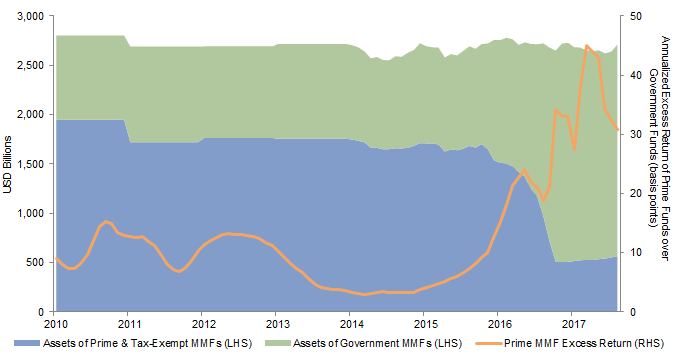

Prime money market funds held the majority of industry assets a few years ago. Now, they are bit players, with only a 16% market share of the US money market fund industry. But as their importance (and asset levels) recede, the yield premium offered by prime funds has increased notably.

For more information on these reforms, please see the August 2015 issue of Quarterly Regulatory Update.

Over the past three years, nearly $1 trillion in assets have flowed out of prime funds, due primarily to regulatory changes that went into effect nearly a year ago.[2]To summarize, the changes went into effect last October and require institutional prime money market funds to institute a floating net asset value and to establish a framework for imposing redemption … Continue reading

Prime funds used to be big buyers of commercial paper and other assets that have been blessed by regulators and ratings agencies as being safe for prime funds. As buyers have gone wanting, yields for this paper have risen.[3]Of course, yields have also risen for Treasury bills, given the Federal Reserve’s policy rate increases, but the yields on non-Treasury paper have moved up more quickly. From 2010 through 2015, institutional prime funds yielded only about 8 basis points (bps) higher than institutional government funds on average. Today, they yield 31 bps more than government funds.

Assets of Prime and Government Money Market Funds and Return Premium

January 31, 2010 – August 31, 2017

Sources: Investment Company Institute and Thomson Reuters.

Notes: Excess return data are monthly. AUM data are annual until 2014 and weekly from that point forward. Prime MMF Excess Return represents annualized three-month return of the Lipper Institutional Money Market Index over the Lipper Institutional US Government Money Market Index.

While Treasury money market funds are a great choice for the majority of US institutions’ cash investments, those investors that carry more cash than they will need for operational purposes might consider prime funds as a destination for the excess amount. A 31 bp premium on a $10 million balance equates to $34,000 annually. Another way of thinking of the 31 bp yield premium is that it is larger than the yield difference between three-year and five-year Treasury notes, even though the interest rate risk on the five-year note is much larger.[4]A 100 bp increase in yields would cause the five-year Treasury to fall by nearly 5%, while the three-year bond would fall less than 3%.

Some investors have, in recent years, used bank-deposit products (which allocate client funds to dozens or hundreds of banks in sub-$250,000 portions, preserving the FDIC’s deposit insurance). While yields on those products used to be well above those of money market funds, they now struggle to keep pace with yields even of Treasury money market funds (bank deposit rates often lag in tightening cycles). Investors that can tolerate the risk of a redemption fee, gate, or net asset value adjustment on a portion of their cash holdings might now consider prime funds for that incremental piece.

Ready for Their Closeups?

Fintech Firms Grabbing Regulatory Attention

Attention fintech companies: Regulators want you. . . and sometimes actually in a good way. Financial technology (fintech) companies, which span a wide range of activities in the financial system, are an object of regulators’ attention. While banking and securities laws originally written in the 1930s and 1940s did not exactly contemplate the rise of these technology companies, regulators are anxious to move these firms out of the shadows (given the regulatory focus on the impact of shadow banking on the financial system) and into the well-lit mainstream of regulatory oversight.

Over the past several months, derivatives market regulator the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), federal banking regulator the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), securities regulator the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and individual US state banking regulators have all taken actions addressing the mushrooming fintech business segment. These companies have gained remarkable traction, raising an estimated $3.5 billion of capital in the first half of 2017. They provide a wide range of services, including mobile payment apps, marketplace lending, credit score assistance, mobile trading, and operational solutions for businesses. Regulators expect the momentum to continue, and that these companies will have a key role in financial innovation in the future.

In some cases, regulators are establishing “Innovation Councils” or similar groups designed to provide assistance to would-be fintech companies in development. In May, the CFTC announced three initiatives aimed at fintech companies. First, it established a central point of contact at CFTC to help companies better navigate the regulatory landscape and understand current initiatives. Second, it announced approval of an initiative labeled “LabCFTC,” which is intended to encourage market-improving fintech innovation. Finally, the regulator announced plans to establish an internal capability of evaluating new technologies while also seeking to adopt technology to improve its own operations. CFTC is not unique in its approach as both the SEC and the OCC have established groups and held forums to assist (and learn from) fintech companies and entrepreneurs. The United States is not alone in encouraging fintech development—the governments of Hong Kong and the United Kingdom established similar programs in 2016.

Despite the US administration’s stated interest in decreasing regulation, fintech companies are likely to find themselves subject to more regulatory attention than in the past. However, this seems to reflect how well integrated into the financial system these companies have become. It also reflects regulators’ recognition that the rising millennials will drive continued growth in the field. Companies offering mobile payments apps or lending platforms may currently partner with brick-and-mortar (and highly regulated) financial companies. The OCC recently released guidance for banks on meeting their oversight obligations when partnering with these technology companies. The answer—you guessed it—will likely entail more operational, compliance, and infrastructure requirements for fintech companies. Meanwhile, in July, the SEC released an investigative report concluding that under some circumstances virtual coins or tokens should be treated as securities, and trading platforms for these digital securities may be required to be registered. This approach establishes the SEC’s potential reach over cryptocurrencies.

The next frontier? Meet your new specially chartered national bank! The OCC proposed a special purpose national bank charter for fintech companies that directly engage in banking activities outside of deposit taking. If the OCC moves forward, fintech companies will no longer need to rely on business models involving partnering with regulated entities. This paves the way for further growth in the fintech space. State banking regulators are less than enthused at this potential development and earlier this year filed suit to block the OCC from granting these specialized charters. While all of that works its way through the courts, some fintech companies have found other ways to pursue their ambitions. In July, Varo Money announced that it applied for a full national bank charter, which would make the company a full-service, mobile-only bank. Might the fintech revolution cause a resurgence in the number of new banks chartered in the United States? Only time will tell, but for now, fintech companies seem to have plenty of options for expansion in a changing regulatory environment.

California Dreamin’. . .

. . . Of Better Fee and Expense Disclosure

Please see the May 2016 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on ILPA’s efforts.

Private funds—including private equity funds—continue to evolve their disclosure policies for fees and expenses amid changing regulatory requirements and industry standards. In the United States, the SEC has publicly taken private equity managers to task, pushing for better disclosure policies around manager fees and compensation. In 2015, several large private equity firms found themselves in the crosshairs and were ultimately subject to fines for improperly disclosing fees or other costs. By early 2016, private equity industry group Institutional Limited Partners Association (known as ILPA) released a “best practices” template for disclosing fee and expense information.

Even with the continued industry focus on fee and costs disclosures, the state of California passed a law requiring all public pensions to disclose information about fees paid to alternatives managers, effective January 1, 2017. Commentators noted that the California law applies to both state and municipal pensions—and that over the long term it could have a chilling effect on smaller funds’ ability to access alternatives managers. At the other end of the size spectrum, $324 billion pension giant California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) recently announced it was reviewing its commitment to private equity, citing continued public disclosure pressures among its considerations for revisiting the strategy.

While disclosure policies of private equity funds have largely been in the spotlight, hedge funds were also pulled into the California law. To date, there has been little indication of whether the new law will have a significant impact on hedge fund investments by pubic pensions. However, given the better liquidity structure of hedge funds, it appears these firms are better positioned to “upgrade” their investor bases if managers find the new law too burdensome. For now, industry observers must be content to watch and wait given that this new state law applies to new investments and additional commitments made to funds beginning in 2017.

Mary Cove, Managing Director

Sean McLaughlin, Managing Director

Footnotes