In this Edition:

- Mutual fund liquidity back in the spotlight

- New rules and regulations under consideration by several regulatory bodies

- Regulators use FCPA to follow the money

- Debt financing rules sharpen

Mutual Fund Risk Reduction

SEC on Illiquid Assets: Put a Lid on It!

Following recently implemented money market fund reforms (see sidebar), new liquidity management and reporting rules are on the horizon for US mutual funds. In October, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved regulations requiring mutual funds to address portfolio liquidity in a systematic way.

Under the new rules, US mutual funds will be required to develop liquidity risk management programs by December 2018.[1]Smaller entities have until June 2019. The programs are intended to reduce the risk that a fund will fail to meet redemption requirements and to limit the dilutive impact of distressed sales on remaining shareholders and the markets more broadly. To do this, programs must (1) classify holdings within four pre-defined liquidity tranches, (2) determine the portion of the portfolio that must remain “highly liquid,” and (3) maintain a 15% cap on illiquid investments.

Other than the specific cap on illiquid assets, the SEC largely left it to funds to determine the parameters of their liquidity risk programs. This will put the burden on fund boards and managers to assess critically the liquidity of their core investments, the stability of their investor bases, and the likely impact of a stressed market on investment liquidity and redemption requests. These types of factors will help determine the proportion of “highly liquid assets”—cash or those capable of being converted to cash within three days—to be held by a fund.

The specific 15% limit on illiquid securities defines them as investments that cannot be sold within seven days without significant price impact. Bank loan or leveraged loan funds may have gotten a bit of a reprieve in the final version of the liquidity rules, as trades within the tiers below “highly liquid” need not be convertible to cash (i.e., settle) within a set period of time. Nevertheless, industry group the Loan Syndications and Trading Association noted the SEC’s focus on loan funds during the regulatory development process, and that the Commission said it is appropriate for boards to consider whether the open-ended mutual fund format is appropriate for some types of investments. The good news: LSTA views the regulations as one more reason to work on improving settlement times for traded loans.

With the adoption of these new liquidity rules, the SEC also gave funds the ability to institute “swing pricing.” This mechanism is akin to entry and exit fees charged by other types of commingled funds and is intended to keep transaction costs with buying or selling investors. Generally, this change should be good news for long-term investors as it may reduce costs going forward.

Finally, the SEC also adopted additional reporting requirements designed to give the regulator better insights into mutual fund risks. Firms must provide information regarding liquidity positioning, which is intended to enable better aggregation of data for market surveillance purposes. These new requirements will begin to take effect in mid-2018 and may provide further insights into the liquidity challenges brewing in the funds marketplace.

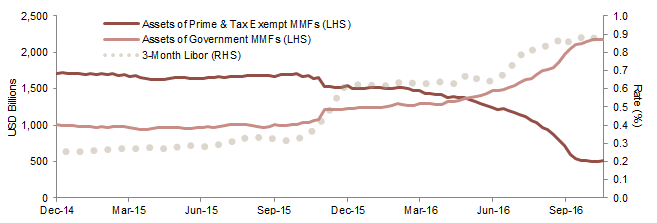

New Liquidity Rules Change the Money Market Landscape

As we previewed in both our August 2016 and August 2015 editions, new liquidity rules went into effect on October 14 that sharply limited the appeal of prime money market funds. In response, investors have rushed into government money market funds, with the transition accelerating in September and October. So far in 2016, combined assets of prime and tax-exempt money market funds have shrunk by 65% (nearly $1 trillion). Correspondingly, assets in government money market funds have increased by 73% ($887 billion).

The stampede has left some banks, municipalities, and others who fund in short-term securities markets scrambling to replace their sources of liquidity. The three-month Libor rate has risen by 30 basis points (bps) since the end of June, despite no increase in the Federal Funds rate, leaving Libor a full 59 bps higher than three-month Treasury bill yields.

Money Market Fund Assets Under Management and Three-Month Libor Rate

December 31, 2014 – November 16, 2016

Sources: Investment Company Institute and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Note: Data are weekly.

Regulators Ponder Next Moves

More Is More?

Financial regulators globally have remained hyper-focused on identifying and moderating sources of systemic risk since the global financial crisis. While the US Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act went so far as to establish systemic regulator the Financial Stability Oversight Council and endowed it with the power to impose additional requirements on firms it designates as “systemically important,” little consensus has emerged on how to evaluate the asset management industry.

US regulators initially seemed bent on developing a framework for designating asset managers as systemically important, replicating the approach used for large banks and some large non-bank financial companies. After much “education” by market participants about the nature of the risks in the asset management business, the SEC appeared to shift to an approach focused on the regulation of specific activities.

However, a recent release by G-20 regulator the Financial Stability Board (FSB) appeared to keep both approaches in play.[2]Financial Stability Board, Proposed Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerability from Asset Management Activities, June 22, 2016. Though the crux of FSB’s consultation focused on investment management activities, the group did not rule out imposing standards on large asset management firms as well. At the same time, national regulators are, in some cases, taking action to bulk up individual asset management firms.

FSB’s release included a proposal focused on liquidity mismatches between funds and their underlying investments that could have significant impact on the US fund offerings. Though recently approved SEC regulations regarding mutual fund liquidity (discussed in the previous article) partially address liquidity risks in the funds market, the FSB is pushing for more. The FSB explicitly raises the question of whether some less liquid investments are appropriately held in highly liquid fund vehicles. Given expressed concerns about lack of liquidity in some corners of the credit markets, funds focused on these types of investments could find it harder to operate under tougher liquidity rules. Additionally, the FSB consultation raises questions about whether mechanisms such as gates or withdrawal penalties should be used to reduce the likelihood of disruptive redemptions from funds in the event of a crisis. Any move toward gates or reduced investor liquidity in mutual funds would be a big shift for the US mutual fund industry, which has benefited from investor confidence in the liquidity of fund investments.

For more on this, please see our August 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update.

The use of derivatives and leverage by asset managers has also been a focus of both the SEC and FSB. In 2015, the SEC proposed new regulations relating to funds’ use of derivatives, including some initiatives that might restrict the ability of highly leveraged strategies to operate. To date, the SEC has not finalized these proposals, and it seems possible that new regulations may not be implemented until a new administration is in Washington, if at all. Nonetheless, asset managers should expect more scrutiny of their use of leverage, as the FSB has proposed moving toward standardized disclosure on the use of leverage that would enable regulators to take action if they perceive systemic risks rising.

Despite the US move to regulate asset management activities, asset managers themselves remain a focus of some national regulators. During third quarter, UK-based Aberdeen Asset Management disclosed that the UK Financial Conduct Authority had required the firm to increase its minimum required capital buffer to £475 million, an increase of more than 40% from its previously required £335 million level. While publicly traded Aberdeen disclosed this change, commentators expected that the firm was not alone in facing enhanced capital buffer requirements.

FCPA Enforcement At New High

PI, Hedge Funds: Beware of Risky Business

The general partners (GPs) of private equity funds and managers of hedge funds that invest in other jurisdictions may be taking another look at their operations and governance in the wake of enforcement actions under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). The FCPA prohibits firms from bribing foreign officials to secure or retain business. In September, the SEC settled with Och-Ziff Capital Management over charges that Och-Ziff looked the other way as government officials in Africa were bribed to secure investment in Och-Ziff funds and to secure mining contracts and other assistance. The settlement, which involved both the management company and executives at Och-Ziff, reportedly totaled more than $200 million.

The SEC announced that during the fiscal year, it initiated a record 21 FCPA-related enforcement actions. The agency has created a unit to focus on private funds, and over the past two years, financial services firms have been the focus of 15 public FCPA investigations—the fourth-highest industry on the enforcement list.[3]The three highest industries on the enforcement list are manufacturing services, natural resource extraction, and technology (in descending order).

For private equity and hedge fund managers, compliance risks are concentrated in two areas: fund raising and management of investments. Using placement agents in fund raising is one thing to watch for, particularly when the placement agents have close connections to a sovereign wealth fund or pension funds. Regulators generally consider these pools to be state-owned enterprises, and their employees to be government officials. In management of investments, a fund’s multiple portfolio companies also can put the GP at risk of an FCPA violation, if the GP is not closely involved to be sure each portfolio company and its related entities are fully compliant. The GP needs to understand who all beneficial owners are in complicated joint ventures, and must scrutinize the reason for (and reasonability of) transactions.

While it seems unlikely that limited partners would face FCPA-related liability stemming from their investment in a hedge fund or private equity fund, they could suffer reputational damage as an investor in a fund tainted by FCPA-related scrutiny or prosecution. As part of our due diligence process, Cambridge Associates evaluates the robustness and independence of the compliance function at funds. During our evaluation, we provide feedback to GPs about best practices. Of course, even a fund’s robust compliance efforts may sometimes be thwarted by a joint venture partner, portfolio-company manager, or third-party placement agent. Given the SEC’s stepped up enforcement and particular focus on private funds, scrutiny of the compliance function as part of the investment process is critical.

Debt Financing Rules Sharpen

Higher Debt Could Pinch Returns

Since 2013, US bank regulators have been publicly prodding banks to limit loans to heavily indebted companies (these loans were often used to finance private equity buyouts). The push seemed to be regarded by the industry more as grandfatherly advice than as a line in the sand. And initially, the prodding did not seem to amount to much.

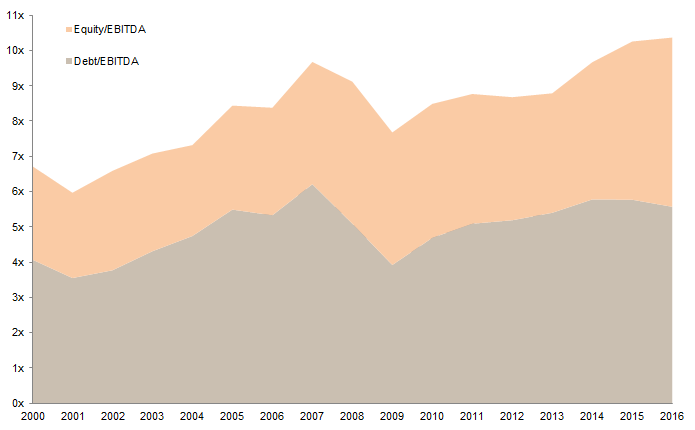

In the intervening years, regulators have given much sharper guidance on what loans were subject to review, and what financial metrics would be scrutinized. Now, to be considered “clean,” debt should generally total no more than six times the issuer’s operating earnings (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization—EBITDA).

Given the regulatory thumbscrews being applied to bankers, are heavily debt-financed buyout transactions no longer getting done? They still are, but non-bank lenders are increasingly being tapped for some of the financing. In 2007, more than half of leveraged buyouts saw debt/equity ratios over 6x. This dropped to zero in the financial crisis, but has mostly bounced back. This year and last, around 40% of buyouts topped a 6x debt/equity ratio. However, “shadow” banks are increasingly providing some of the financing. In fact, in the funding “league table” for buyout financing, shadow banks this year hold a 16.2% market share, up from just 6.5% three years ago. While we have not seen data on the differences in terms between loans arranged by regulated banks and shadow banks, it stands to reason that banks with government-insured deposits may have a lower cost of capital than shadow-bank entities.

Even with new entrants to the lending markets and with miniscule or negative interest rates on sovereign bonds, appetite for risky credit is not limitless, and buyout sponsors have been boosting equity contributions as deal values rise. Debt/EBITDA, which briefly topped 6x at an aggregate level in 2007, has remained around 5x in recent years. As total deal values have pushed close to 11x for the first time, equity contributions have grown, reaching 5.4x in 2016 (which would be a record, if the current level persists through year end—the aggregate equity contribution has averaged 3.4x).

Source: Standard & Poor’s LCD.

Notes: Data for 2016 are through October 31. Purchase price multiples include fees and expenses. EBITDA, an operating-earnings metric, refers to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Debt/EBITDA represents senior debt/EBITDA, subordinated debt/EBITDA, and others.

Higher equity contributions, when combined with the potential for higher debt costs (if the increased use of shadow banks nudges loan spreads higher), could pinch returns for private equity investors. That said, high deal prices (and the potential for higher policy rates in coming years) will pose a greater challenge than regulatory pressures.

Mary Cove, Managing Director

Sean McLaughlin, Managing Director

Footnotes