In this Edition:

- Regulatory themes to watch for in 2017

- Actively managed investment strategies face new legal, regulatory challenges

Looking Forward in 2017

The Pendulum Swings Back (Probably)

In the United States, 2016’s regulatory initiatives were largely continuations on prior themes. With a radically different administration in town, plan to say goodbye to all of that. And, if early actions by the Trump administration are any indication, 2017 could prove to be a banner year for change. What could happen? Really, it is anyone’s guess. As we consider some common concerns about financial regulations and the possibility of creating great headlines, here are some thoughts.

Banks and Banking. Anything that might keep a lid on economic activity is subject to some risk of change. Many of the post–global financial crisis (GFC) financial regulations have been blamed for having a disproportionately negative impact on small banks. Expect to see regulators taking a more nuanced approach to banking regulations based on the size and complexity of the organization. Portions of the Volcker Rule, which prohibits some types of proprietary trading, could likewise be changed. Regulations implementing Volcker are widely believed to have contributed to declining dealer inventories, consequently reducing bond market liquidity. It is certainly possible that the rule could be relaxed going forward.

Tax Reform. Tax law changes could create opportunities for managers. A “tax holiday” enabling repatriation of the estimated $2.6 trillion held overseas by US corporations could also free up cash for share repurchases, acquisitions, or other initiatives that could become opportunities for event-focused managers. And, of course, a significant change in the corporate tax regime could provide opportunities for active managers, as winners and losers within industries may begin to shift around. Tax rate changes could also be impactful for market segments such as municipal bonds and master limited partnerships, whose prices reflect their tax favored status. Another structural tax reform that could impact a range of investments is the elimination of deductibility of interest payments for corporations. This has implications for private equity firms, highly levered businesses, and also the corporate bond market. A Bank of America analysis suggested that if the interest deduction goes away, the corporate bond market could eventually shrink by 30%. Finally, will there be a “carried interest” tax on the horizon? Both presidential candidates spoke about addressing taxation of carried interest during the presidential campaign. Could fund managers see an erosion of their economics? And might that translate into changes in fee structures for investors?

For more on these topics, please see the November 2015 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update.

Mutual Funds. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) initiative to regulate asset management activities seems unlikely to move beyond where it is today. Regulations restructuring the money market fund landscape, revamping mutual fund liquidity requirements, and enabling swing pricing were implemented in 2016. However, proposed regulations on fund leverage and initiatives regarding resolution plans for asset managers—both of which were floated by regulators—seem unlikely to garner the support of the new administration.

Hedge Funds and Private Equity Managers. To date, there has been seemingly little talk of reducing direct regulation of hedge funds and private equity managers. These firms, which were required to register with the SEC post-GFC, seem unlikely to see a roll back in registration requirements. Admittedly, compliance and reporting obligations driven by regulators’ interest in understanding risks in the financial system are not trivial and have had an impact on overall operating costs for managers. Nonetheless, it seems logical that making things simpler and cheaper for hedge funds and private equity managers would not be high on the list for a populist administration.

Many post-GFC regulatory changes that have impacted hedge fund managers. Some have reduced liquidity and thus added to market volatility; others arguably created opportunities for hedge funds. Expect this ground to shift. For example, heightened antitrust scrutiny has contributed to widening deal spreads—good news for event-driven managers. The risk of serious antitrust challenges could certainly recede, narrowing spreads and prospective returns as a result. Registration and other regulatory disclosure requirements have meaningfully increased the costs of running hedge funds, creating barriers to entry and benefiting established funds. Liberalization of portions of the Volcker Rule and other bank regulations may lead firms to re-assess lines of business and move back into some of their former domains—acting as dealers (that, you know, actually hold inventory) in the bond markets, for example. In theory, bringing the banks back into the marketplace should provide more liquidity to the system. Should banks be permitted to move aggressively back into proprietary trading, hedge funds would again be competing with larger, more leveraged pools of capital. As is apparent from even this short list of issues, the impact on hedge funds will vary on the specific changes being made. Given the complexity of untangling the financial regulatory framework that has been put in place over the past seven years,[1]The Dodd-Frank Act passed into law in 2010. funds will likely have time to adjust as the path forward becomes clearer.

Please see the November 2015 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on this topic.

Private equity firms, too, could see shifts in their opportunity set. Liberalization of banking regulations focused on encouraging lending could certainly ease lending standards to corporate buyouts. In particular, regulatory guidance that has effectively capped bank lending at debt to EBITDA[2]EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. ratios above 6x could be rolled back once the new administration puts new banking regulators into place, giving managers the opportunity to finance more highly leveraged transactions. And risk retention rules—which effectively impacted managers of collateralized loan obligations—may also change, reopening the spigot for the re-distribution of corporate credit into the broader marketplace. The changing dynamics across industries, whether due to prospective financial regulatory, environmental, trade, or tax policy changes may also have an impact on private equity firms as they seek to determine appropriate purchase prices for established businesses. Given the current level of uncertainty, a slowdown in capital deployment could happen as firms decide where to pick their spots.

In early February, President Trump signed an executive order that established a framework for the administration’s approach to reducing financial regulatory burdens, specifically around the Dodd-Frank Act. Generally, the administration is seeking to reduce regulation it deems detrimental to economic growth and “vibrant” financial markets, but it is also supportive of moves that address systemic risks and reduce the possibility of taxpayer-funded “bail-outs.” Under this order, the Treasury secretary would seek feedback from other agencies and report back to the president with findings within 120 days. Stay tuned … it’s going to be “tremendous” or, at the very least, definitely not a “disaster.”

Ahoy, Regulatory and Litigation Activities!

More Wind Behind Index Fund Sails

Active investment managers have been facing strong headwinds over the past few years, from a performance perspective and a business perspective, and now two recent fiduciary/litigation developments—the US Department of Labor’s Fiduciary Rule, and a spate of lawsuits against 401(k) and 403(b) sponsors—are likely to exacerbate the industry’s challenges. The continued migration towards passive investments is a real threat to the business model of many active managers, and investors that prefer to select active managers must ensure that their managers can remain intact if assets (which have been roughly flat in recent years, as the asset boost from positive market returns was offset by outflows) begin to contract.

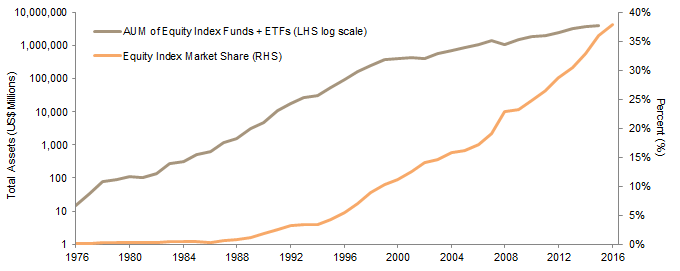

Active equity managers have seen outflows for most of the past decade. It is difficult to ascribe motivations to their shareholders, but underperformance is probably one motivator. Not since 2007 have the majority of large-cap funds outperformed the S&P 500 Index in a calendar year, for example.[3]Please see Aye M. Soe, “SPIVA® U.S. Scorecard: Year End 2015,” S&P Dow Jones Indices Research, March 11, 2016; and Michael Mauboussin et al., “Looking for Easy Games: How Passive Investing … Continue reading However, active managers have been losing market share to index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) for decades, so cyclical active management performance is clearly not the sole factor. In 1995, index funds accounted for only 4% of US-domiciled mutual fund assets, but by 2005 that share had quadrupled, and today it is approximately 38%. This is not just a US phenomenon: Moody’s forecast in a recent report that passive investments would surpass active investments on a global basis sometime between 2021 and 2024.

Sources: Bogle Center for Financial Market Research, Goldman Sachs, and Vanguard Group.

Notes: Assets under management data are through August 2015 and equity index market share data are through August 2016. Assets represent all equity index funds and exchange traded funds that are domiciled in the United States, regardless of their geographic focus. The market share line represents the share of these indexed products across the full universe of such funds (indexed plus active). The universes employed in the two datasets may differ slightly.

Migration away from active management by individual investors has been slow and steady, from nearly 100% active in the 1980s, falling below 90% early in this millennium, and subsequently falling below 80% over the last few years. Institutions adopted index funds earlier than individuals; however, in recent years they have moved very aggressively away from active products (from about 60% active five years ago to 40% today). We believe that two relatively recent factors will continue to push institutional allocations in the passive direction.

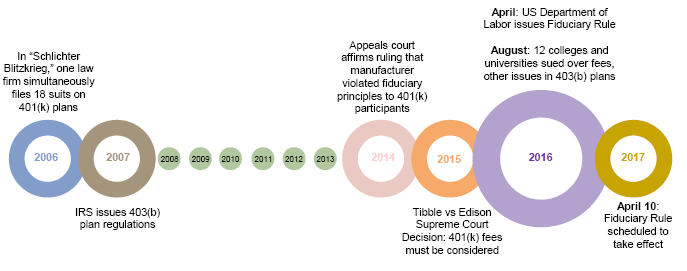

First, over the past decade, and particularly over the past two years, dozens of defined benefit contribution plan sponsors have been sued, with the plaintiffs alleging that their 401(k) or 403(b) plan has too-costly fund options. Defendants have included prominent corporations such as Chevron, Intel, and Verizon, as well as universities such as Yale and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Plan sponsors have increasingly moved toward using institutional share classes rather than retail share classes, as well as shifting toward index funds. In 2006, 79% of plans offered at least one index fund, and by 2013, the percentage of plans was nearing 90%. The percentage of plan assets in index funds jumped from 17% to 26% over that same period. With sponsors much more fee conscious and litigation-aware today, use of index funds (and of target date funds, which often include index fund components), will likely continue to grow within 401(k) and 403(b) plans.

Sources: Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP, Nixon Peabody LLP, Pensions & Investments, Schlichter Bogard & Denton LLP, US Department of Labor, and The Wall Street Journal.

The second regulatory development spurring adoption of passive investments is more recent: the Labor Department’s Fiduciary Rule. This rule is scheduled to be enacted in April, and while the Trump administration is seeking to abolish the rule, broker-dealers have already made structural changes to accommodate it, and it is unlikely those will be undone any time soon. The Fiduciary Rule specifies that advisors affiliated with broker-dealers will now need to act as fiduciaries to their clients with regard to retirement plan assets. Under the upcoming rule, no longer will an IRA investment need to merely be “suitable,” it must now be in the client’s best interest. Some brokerage firms are migrating toward advisory accounts and away from commission-based structures, and they are likely to continue to move away from selling load funds in retirement accounts. This will particularly impact the estimated $4 trillion in IRA assets that are currently managed in traditional, commission-based brokerage accounts.

The migration to passive strategies is likely part cyclical and part secular, and when cyclical underperformance factors ebb, active manager performance will improve somewhat,[4]That is not to say that the average active manager will consistently outperform the index at that point. We expect that in equilibrium, the average active manager will roughly match the index before … Continue reading but we would not expect to see active managers recapture significant market share. In the midst of frequent lawsuits, plan sponsors do not appear eager to feature expensive actively managed funds in their defined-contribution plans. And broker-dealers have little incentive for their financial advisors to push load funds and other expensive products, given their new requirements as fiduciaries. At best, actively managed external products at competitive fees will now be on a level playing field with ETFs and other index funds.

While the path to greater utilization of passive investments will continue to meander, we believe it is a one-way road. For investors that continue to use active managers, it is perhaps more important than ever to determine whether their managers will to remain organizationally stable in the event assets (and therefore fee revenues) continue to contract.

Mary Cove, Managing Director

Sean McLaughlin, Managing Director

Footnotes