Well-diligenced private investments in a skillfully constructed portfolio are important growth drivers that have helped pension funds deliver superior performance and increased the probability of meeting or exceeding long-term required returns

- Private investments offer pension funds the opportunity to significantly increase returns when implemented well, capture some diversification benefits, access a more complete opportunity set, and improve funding levels. For example, if private investments can beat public equities by 300 bps per year (as commonly targeted), then shifting 15% of assets from public equities to private investments would boost a pension fund’s total portfolio return by 45 bps per year.

- Particularly for higher-returning private investment strategies, the dispersion between manager returns is significant, underscoring the importance of selection.

- Illiquidity, complexity, transparency, and fees are important but surmountable considerations.

Many defined benefit pension funds are developing strategies to increase expected investment returns and improve funded status. Private investments have the potential to increase portfolio returns significantly and bring other attractive attributes as well. They have demonstrated outperformance versus public markets over appropriately long periods of time and should play an integral role in growth strategies for pension funds that can lock up even a limited amount of capital.

Extracting value from private investments requires skill in all stages of the investment process and an experienced and well-resourced team of private investment professionals. In this research note, we explore how pension funds may benefit from private investments, discuss key considerations, and develop a framework for successful implementation.

Return Premium Over Equities

Higher-returning private investment strategies—venture capital, growth equity, buyouts, and select debt-related and real assets strategies—are expected to outperform public equities over the long term. Other private investment strategies can offer attractive portfolio benefits as well, and Cambridge Associates incorporates a wide range of private strategies in portfolios for additional objectives including diversification benefits, cash flow yield, and in some cases inflation sensitivity. This research note focuses on the higher-returning strategies.

Private investments have generated excess returns from multiple sources, including manager value add and access to a differentiated opportunity set. The structure of private equity investments enables general partners (GPs) to align management and shareholder incentives, maintain a longer-term focus, implement operational improvements, execute strategic acquisitions and geographic and product-line expansion, respond to market opportunities and challenges, and optimize capital structures. Some strategies—for example, special situations, opportunistic credit, secondaries, and distressed—find attractive investment opportunities during market dislocations, when an owner has a liquidity constraint, or when there is a company-specific issue or notable change. Some find idiosyncratic or other types of investment opportunities not available in the public markets. Venture capital allows investors to invest at an earlier stage in high-growth companies. Tapping opportunities to increase returns prudently, expand the sources of returns wisely, and diversify portfolio risk is always additive and particularly important in the current market environment.

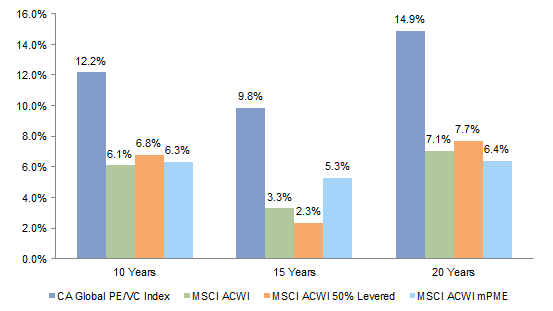

While private investments have the potential to generate a significant return premium over traditional public investments, harvesting this return premium requires effective planning, diligence, portfolio construction, manager selection, monitoring, and patience. Private markets cannot be accessed via a passive index-tracking investment, and the dispersion between manager returns is substantial. Figure 1 demonstrates the exceptionally wide range of returns across managers within the same strategy and vintage year (across many segments of global private markets). The charts also highlight the importance of manager selection and portfolio construction.

Figure 1. Manager Dispersion in Private Investments

Vintage Years 1998–2008 • As of December 31, 2014 • US Dollar • Internal Rate of Return (%)

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Based on data compiled from Cambridge Associates’ proprietary investment manager database. Includes all funds tracked in each asset class specified, including fully liquidated partnerships, formed between 1998 through 2008. US Private Equity data compiled from 694 funds in the private equity universe including those identified as buyout, private equity energy, growth equity, and mezzanine funds. US VC data compiled from 827 venture capital funds. European PE data compiled from 212 private equity funds. EM PE/VC data compiled from 330 global emerging market private equity and venture capital funds including funds investing primarily in Africa, emerging Asia, emerging Europe, Latin America and Middle East ex Israel. Internal rates of return are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest. CA Research shows that most funds take at least six years to settle into their final quartile ranking, and previous to this settling they typically rank in 2-3 other quartiles; therefore fund or benchmark performance metrics from vintage years after 2008 are excluded from this analysis and less meaningful at this time. Scale has been capped at 150 for graphing purposes.

Pension funds can improve their odds of successful implementation by retaining capable staff and accessing outside expertise to supplement or help inform the in-house team. Alternatively, pension funds can partner with or outsource to an experienced and well-resourced private investment advisor on a fully delegated or semi-delegated basis, or via a parallel-governance process.

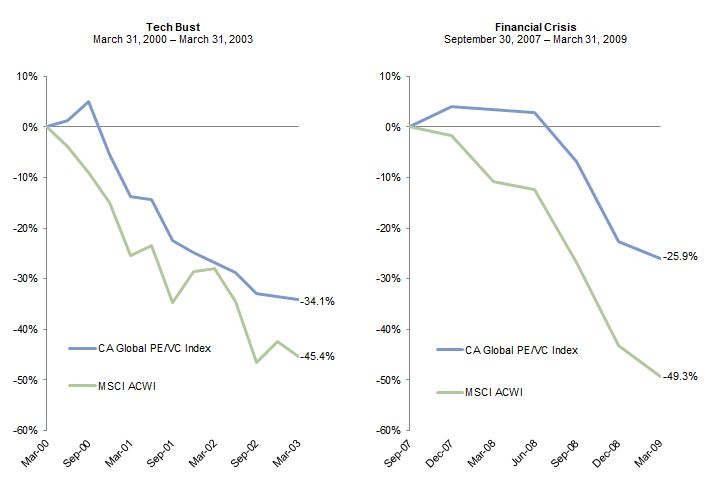

The CA Global Private Equity/Venture Capital Benchmark universe has surpassed the target many investors have for private investments—to generate returns that exceed public equities by 300 bps or more over the long term (Figure 2). The universe significantly outperformed a 50% levered public equity index as well, demonstrating the value that private investments can add beyond financial leverage alone. Recognizing that leverage levels are modest or nil in venture and growth equity strategies, we looked at this analysis versus our buyouts universe alone, which has also significantly outperformed levered and unlevered public equities. Finally, using a public market equivalent analysis based on public equities, our CA Global Private Equity/Venture Capital Benchmark universe outperforms by over 300 bps per year as well.[1]Public market equivalent (PME) analysis takes into account the size and timing of actual private investment contributions and distributions in the calculation of a public market index return and … Continue reading We also note that private investments are generally exited at higher valuations than recent unrealized GP valuation marks. For example, our recent analysis of US private equity exits in our data universe showed a range of results, yet an average uptick of 11% when comparing the total value to paid in multiple at exit versus the unrealized total value to paid in multiple six months prior to exit.

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any expressed or implied warranties.

Notes: CA Global PE/VC Index reflect pooled returns net of management fees, expenses, and carried interest. These returns include all global private equity (buyout, private equity energy, growth equity, and mezzanine funds) and venture capital funds tracked by Cambridge Associates over the specified periods. MSCI ACWI and MSCI ACWI 50% Levered are quarterly time-weighted returns. The 50% levered returns assume borrowing at three-month LIBOR. MSCI ACWI mPME is a public market equivalent analysis that assumes the cash flows from the CA Global PE/VC Index were invested in the MSCI ACWI. The mPME therefore represents an internal rate of return (IRR) calculation. MSCI ACWI returns use gross of dividend taxes prior to March 31, 2001, and net of dividend taxes thereafter.

Portfolio Volatility Dampening Effect

In addition to the potential to deliver a long-term return premium, private investments may help pension funds reduce portfolio volatility and thus funded-status volatility. Private investments are valued on a quarterly basis, and the nature of the investments causes some stickiness in the portfolio marks (to the upside and downside). Comparing shorter-term volatility and performance across private and public markets is inherently difficult. Nevertheless, the standard deviation and up-and-down market performance of investment values are important to many investors.

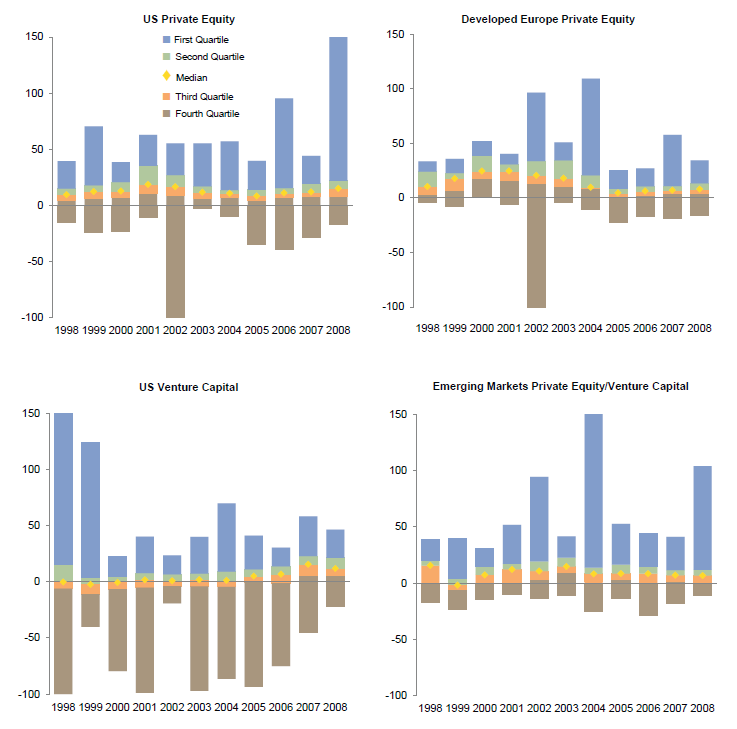

Figure 3 presents the cumulative performance of our CA Global Private Equity/Venture Capital Index relative to public equity markets during the 2000–03 tech bust and the 2007–09 financial crisis. Our private equity index realized significantly smaller drawdowns than public equities during both bear markets; the private equity index outperformed by 11.3 percentage points in the tech bust and 23.4 percentage points in the financial crisis.

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” and without any expressed or implied warranties.

Notes: Based on all global private equity (buyout, private equity energy, growth equity, and mezzanine funds) and venture capital funds tracked by Cambridge Associates that were active during the time periods analyzed. Returns for private investments are based on quarterly end-to-end IRRs, which are net of fees, expenses and carried interest. MSCI ACWI returns are based on quarterly time-weighted returns. MSCI ACWI returns use gross of dividend taxes prior to March 31, 2001, and net of dividend taxes thereafter.

Private equity’s bear market outperformance may be attributable to managers’ ability to drive operational and capital structure improvements that preserve value as well as to some extent the lagged nature of private market valuations. Valuation practices can vary slightly across managers, but the aggregate effect is that private investments have been less sensitive to public market movements on both the downside and the upside.

Surmountable Considerations

Well-selected private investments offer the potential for pension funds to increase long-term returns and capture some diversification benefits. Some investors, however, are still reluctant to invest due to the factors below. We understand these concerns, but believe they are surmountable.

Illiquidity. Private investments are illiquid and require investors to maintain a long-term mindset and time horizon. Typical buyout and venture capital funds have ten-to-15 year fund lives and may take six years or more for performance to develop. Other strategies, such as secondaries and private credit funds as well as co-investments and direct investments, tend to generate distributions more quickly. The cash flow profile of private investments can also vary by vintage year, due to the ebb and flow of merger & acquisition activity and capital markets. While exact cash flow planning for a private investment portfolio is not possible, informed pacing as well as disciplined portfolio monitoring can help pension funds manage effectively.

Jill Shaw et al., “A Framework for Benchmarking Private Investments,” Cambridge Associates Research Report, 2014.

Long-Term Time Horizon/Benchmarking. Private investment performance takes many years to become meaningful. Our research has shown that the typical private investment fund takes six to seven years to produce meaningful results. On average, a fund will also fall in three performance quartiles based on a comparison with vintage year peers before settling into its ultimate quartile. This is explained in part because private equity funds typically take five years to deploy capital, and returns often have a “J-curve” effect in the early years when capital is drawn for fees and to make investments, only after which point the value creation initiatives begin and then take time to develop and harvest. This and other factors also make benchmarking of private investments challenging. In our work, we focus on understanding what decisions investors seek to measure and develop benchmarks accordingly. The ability to stay the course over the decade or more required to develop mature performance is critical to realizing long-term success. Private investment performance data are not meaningful and have quite a bit of noise until sufficiently seasoned, so patience, with diligence, is a virtue.

Complexity. Robust private investment portfolios are typically composed of 15 to 30 managers, though small portfolios might use fewer managers and some mature portfolios are far larger. Further, a manager can have one to four active funds with net asset value outstanding at any point in time. Investors considering implementation should be prepared for a larger number of funds in their portfolio given the serial nature of private investment fund raising and since some manager relationships will be discontinued at a future point in time. Co-investments or direct investments, when pursued, add to the number of portfolio holdings as well. While this complexity requires sufficient resources for governance, monitoring, and operations, private investments’ return potential, when captured by investors, merits the additional complexity and effort required.

Transparency. Unlike public companies, most privately owned companies do not have to file public financial statements, making it more difficult for outsiders to obtain in-depth information. Although some exceptions exist, private investment firms are private. These and other transparency-related concerns can be addressed through thorough due diligence, monitoring, and maintaining long-term relationships with market participants. For example, private investment managers often provide access to in-depth data on their firms as well as historical and current portfolio companies when fund raising to meet investors’ due diligence requirements. Experienced staff and advisors also monitor investments on an ongoing basis, providing important perspectives. Operational due diligence additionally supplements investment due diligence.

Fees, Carried Interest, and Alignment of Interests. Fee structures and carried interest on profits are undoubtedly more expensive for private investment funds than for long-only public funds. Yet of note, carried interest is only earned when the GP realizes a profit on an investment and typically only after fees are paid back and the LP has earned a “preferred” return (a baseline specified in fund terms, and today typically about 8%). Most institutions that invest for the long term focus not on fees in isolation but on terms and returns after fees and carried interest. Spending less on fees does not necessarily translate to higher net returns. And for private strategies, net returns have delivered outperformance. Returns for the Cambridge Associates Private Investment Indexes are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest, and, as shown in Figure 2, have significantly outperformed public markets.

Increased investor and regulatory scrutiny, along with investors’ negotiation of fees and other terms, has led to some improvements in GP/LP alignment of interest over the last decade. In our experience, funds have shown improvement in GP commitment amounts, ancillary fee charging practices and offsets, standardized reporting, and carried interest structures (e.g., profit splits, preferred returns, clawback provisions, distribution waterfalls). Other areas of focus for investors include fund sizes, firm assets under management, and allocation practices. While further progress in simplifying and reducing the level of fees and increasing GP/LP alignment of interests would certainly be beneficial to LPs, net returns remain attractive, and the trend on GP/LP alignment continues to be positive.

For more on the co-investment opportunity set, please see Andrea Auerbach et al., “Making Waves: The Cresting Co-Investment Opportunity,” Cambridge Associates Research Report, 2015.

Our investment and operational due diligence teams collaborate throughout the research process to evaluate fees and terms across multiple dimensions, and we advise that our clients conduct legal reviews with experienced counsel. We evaluate investment merits and terms and select managers on the basis of expected net returns to the LP. While there are many fees and practices to watch out for, diligence, discipline, and negotiation certainly help. In an effort to reduce fees and increase returns, a growing number of investors are also pursuing co-investments and to a lesser extent direct investments, further expanding the private investment opportunity set. As with all private investment strategies, co-investments and direct investments each require specific skills to source and evaluate opportunities as well as to consider the portfolio effects of such investments so as to mitigate the risk of adverse selection and unintended (versus intended) concentration.

Headline Risk. Private investments have been in the headlines over fees, carried interest, and other issues and will likely remain in the news. However, focused due diligence can uncover opportunities that can meet and even exceed investment objectives net of fees and other economic charges. Private markets are vast, and broad-brush comments, which are sometimes inaccurate or incomplete, should not dissuade pension funds from pursuing the select strategies and managers that can add value and drive long-term growth.

Successful Implementation Process

Private investment implementation is an ongoing and dynamic process that can be thought of in three stages: planning, portfolio construction and manager selection, and monitoring.

Planning. Proper planning supports effective governance and performance evaluation. The following elements are critical to establish upfront and revisit periodically over time or if key factors change:

- Roles, responsibilities and framework for the investment process, with required resources

- Long-term objectives and benchmarks

- Understanding of the liability’s cash flow profile

- Understanding of the expected characteristics of potential strategies (e.g., cash flow versus capital appreciation, expected return, and time horizon)

- Framework for allocations and commitment/investment pacing

- Strategy, sector, and geographic opportunity set

- Investment type opportunity set (e.g., funds, managed accounts, funds-of-funds, secondaries, co-investments, direct investments)

Portfolio Construction and Manager Selection. Implementation is the crux of the challenge and often the key driver of results. In our experience, the following practices facilitate successful implementation:

- Diversification across sectors, managers, and vintage years without over-diversifying

- Early development of manager and other sourcing relationships

- Comprehensive investment process (investment, operational, and legal) led by people with relevant skill and experience

- Consideration of valuations without trying to time markets

- Being prepared, and positioned, to move quickly on an informed basis when needed

- Seizing attractive access and investment opportunities when others are scared or forced to sell

- Effective planning so as not to be a forced seller

- Maintaining the patience and discipline required to be a successful long-term investor

Monitoring. Continually evaluating private investment managers and the overall portfolio’s development is essential. Combining bottom-up and top-down monitoring provides perspective on past performance and forward-looking assessments. The following factors are particularly important to watch:

- Firm, team, and incentive changes

- Manager generational transitions, where relevant

- Strategy drift, if any

- Assets under management and strategy proliferation

- Portfolio company/project development

- Investment performance across multiple measurements (ideally after results are meaningful)

- Commitment/investment pacing and any changes in key assumptions

Pension funds must ensure they have the right resources in place to be informed, prepared, and able to manage all aspects of the investment process, including governance, oversight, and operational requirements. This experience can be built in three possible ways: (1) fully in-house; (2) complemented in whole or in part by an experienced private investment advisor serving as an extension of the in-house investment team to fulfill specific needs of the investment or governance process—such as in-depth investment and operational due diligence, independent fiduciary opinions, market data, helping to source and/or screen new ideas, and reporting; or (3) outsourced on a delegated or semi-delegated basis to an experienced advisor or investment manager.

Conclusion

When well implemented, private investments can help pension funds generate higher returns and superior performance over the long term, dampen portfolio volatility, improve funding levels, and increase the probability of earning required returns. With the average private equity allocation among US corporate and public defined benefit pension funds at 5.5%,[2]Based on Pensions & Investments data on 256 US corporate and public pension plans as of September 30, 2014. many pension funds—particularly those that are accruing benefits or are significantly underfunded—have the scope to increase their private market allocations. Rigor throughout the investment process is critical as are expertise in planning, appropriate education, a workable governance structure, and a long-term time horizon and commitment. Access to professionals with relevant private investment experience to support execution and maintaining a patient yet diligent long-term approach can improve the odds of successful implementation. Considerations around illiquidity, complexity, transparency, and fees are important but manageable, and some improvements and increased focus on GP/LP alignment is a positive development for pension funds considering investment. As pension funds seek to achieve their objectives in an increasingly challenging environment, private investments should not be overlooked.

Index Disclosures

Cambridge Associates Indexes

Cambridge Associates derives its US private equity benchmark from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of private equity funds. As of March 31, 2015, the database comprised 1,206 US buyouts, private equity energy, growth equity, and mezzanine funds formed from 1986 to 2014, with a value of nearly $564 billion. Ten years ago, as of March, 31, 2005, the index included 587 funds whose value was roughly $161 billion.

Cambridge Associates derives its US venture capital benchmark from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of venture capital funds. As of March 31, 2015, the database comprised 1,576 US venture capital funds formed from 1981 to 2015, with a value of roughly $158 billion. Ten years ago, as of March 31, 2005, the index included 1,053 funds whose value was about $52 billion.

The pooled returns represent the net end-to-end rates of return calculated on the aggregate of all cash flows and market values as reported to Cambridge Associates by the funds’ general partners in their quarterly and annual audited financial reports. These returns are net of management fees, expenses, and performance fees that take the form of a carried interest.

Both the Cambridge Associates LLC US Venture Capital Index® and the Cambridge Associates LLC US Private Equity Index® are reported each week in Barron’s Market Laboratory section. In addition, complete historical data can be found on Standard & Poor’s Micropal products and on our website, www.cambridgeassociates.com.

Europe Developed Private Equity Only custom benchmark information is based on data compiled from 346 developed private equity funds, including fully liquidated partnerships, formed between 1986 and 2013. Internal rates of return are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest. CA research shows that most funds take at least six years to settle into their final quartile ranking, and previous to this setting they typically rank in two to three other quartiles; therefore, fund or benchmark performance metrics from more recent vintage years may be less meaningful.

The Global Emerging Markets Private Equity & Venture Capital custom benchmark information is based on data compiled from 540 global emerging markets private equity and venture capital funds (includes funds investing primarily in Africa, Asia/Pacific–Emerging, Europe–Emerging, Latin America & Caribbean and Middle East–Emerging), including fully liquidated partnerships, formed between 1986 and 2013. Internal rates of return are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest. CA research shows that most funds take at least six years to settle into their final quartile ranking, and previous to this settling they typically rank in two to three other quartiles; therefore, fund or benchmark performance metrics from more recent vintage years may be less meaningful.

MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI)

MSCI ACWI captures large- and mid-cap representation across 23 developed markets and 23 emerging markets countries. With 2,464 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set.

Jennifer Urdan, Managing Director

Max Gelb, Associate Investment Director

Other contributors to this research note include Bill Hoch.

Footnotes