Now that the date of 23 June has been set for the United Kingdom’s referendum on leaving or remaining within the European Union (EU), the market is frantically trying to call the consequences of either outcome on UK and other assets. The resulting cacophony of opinions and statements for and against leaving the EU has demonstrated one Rumsfeldian truth: there are an awful lot of known unknowns (not to mention the other variety), which means that you can paint a respectable picture either way, according to politics and prejudice.

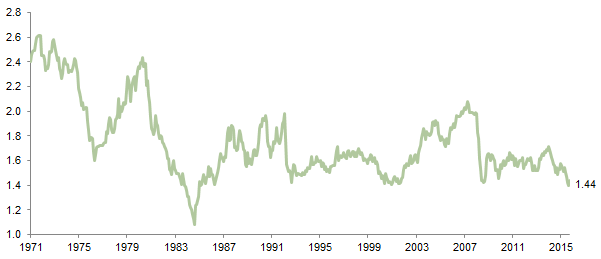

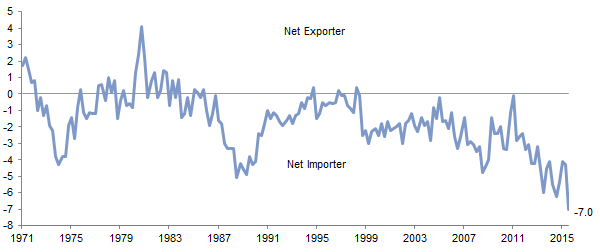

Markets, anticipating trouble, have already put pressure on sterling in 2016, which is down 7.0% versus the euro and 2.5% versus the dollar as of 31 March. The economic consequences of a British exit, or “Brexit” as it has come to be called, could be considerable, though longer term, much would depend on the United Kingdom’s ability to negotiate its trade ties with Europe and the rest of the world, having reverted to small trading statehood à la Singapore or Switzerland.

In the short term, a UK departure would likely see sterling take a further beating, with analysts expecting another 10%–20% fall versus US dollar. UK large-cap equities should benefit from translation effects and enhanced competitiveness, while the financial sector would be heavily affected. UK real estate would probably be hit due to large foreign and finance-related company ownership. UK gilts are a wildcard because they would be caught in the crossfire of more inflation, lower growth, higher budget deficits, and maybe renewed quantitative easing to “save the economy” in the short term.

At the time of writing, betting firms quote the probability of a Brexit at about 35%. Given that sterling has already come under pressure and UK large-cap equities have outperformed in recent months, for non-sterling investors, hedging from current levels below $1.45 would appear inadvisable unless the odds shorten markedly or investors’ sterling currency exposure is large enough to cause excessive downside volatility if Brexit happens. If the odds don’t tighten much between now and the vote, sterling-based investors should consider locking in some currency gains from non-sterling exposure if, for example, the USD/GBP rate dips below recent lows around $1.38, which has historically provided strong support. On the other hand, an unexpected vote to leave would immediately pose the question of how the United Kingdom would be able to finance its large current account deficit and would probably warrant a reduction in sterling exposure.

Just how much might the United Kingdom stand to lose, or to gain, from leaving? Some numbers place the arguments in perspective, focusing on trade, budgetary, and other consequences of a political divorce.

Trading Away a Large Market

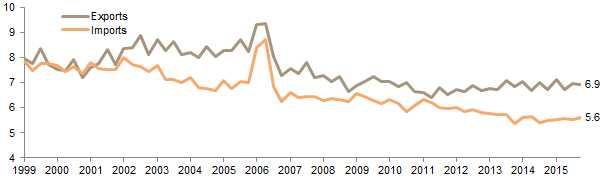

On the trade front, the United Kingdom runs a large deficit in goods, partly balanced by a surplus in services. Goods exports represent about 15% of GDP compared to services exports, which weigh in at about 12%. Around 50% of the United Kingdom’s trade in goods is with the EU (up from around 20% in pre-EU days in the early 1970s), and if you include services, the total is still around a hefty 45%. As total UK exports represent around 30% of GDP, exports of goods and services to the EU represent a not insubstantial 14% or so of GDP (and employ 3–4 million people). This actually understates what is at risk to the extent that a further 13% of UK exports go to countries with free trade agreements with the EU (e.g., Switzerland and Turkey), which would also need to be renegotiated after a Brexit.

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Note: Exchange rate data are monthly.

Sources: Thomson Reuters Datastream and UK Office for National Statistics.

Note: Current account data are quarterly and seasonally adjusted.

The “Leavers” point to Norway’s access to the EU Free Trade Area as a member of the European Economic Area (EEA) and Switzerland’s successful negotiation of free trade agreements with the EU on a sector-by-sector basis (as part of the European Free Trade Agreement). The “Stayers” emphasize the stringent conditions attached. Norway still has to adopt EU regulations, including cost-of-origin requirements, EU product standards, and EU financial rules and regulations. And Norway has to accept the free movement of people, pay welfare benefits to qualifying EU nationals living there, and contribute to the EU budget. All this without having any say or influence on these regulations and laws, amounting to taxation without representation according to the Stay campaign.

The fact is, the weight of the EU’s trade in the UK economy is far greater than the weight of the UK’s trade in the EU economy. With so much more to lose, the United Kingdom would start with a handicap as it embarked on negotiations under the two-year time limit permitted by EU treaties. It is highly unlikely to obtain more favorable terms than, say, Norway, so would need to choose whether it is worth ending up with a similar deal, or going it alone in the hope that broader World Trade Organization (WTO) rules would force down any tariffs and barriers put up by the rump EU.

UK Trade with EU as a Percent of Total UK Trade

First Quarter 1999 – Fourth Quarter 2015 • Percent (%)

Sources: Thomson Reuters Datastream and UK Office for National Statistics.

Notes: Total trade data are quarterly. Total trade includes goods and services.

EU Trade with UK as a Percent of Total EU Trade

First Quarter 1999 – Fourth Quarter 2015 • Percent (%)

Sources: Eurostat and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Total trade data are quarterly. Total trade includes goods and services. Total EU trade excludes trade attributed to the

UK.

Leavers argue that tariffs on goods have come down a lot already, to an average around 4% for countries with most favored nation status, so this might be a small price to pay to be rid of all EU-related obligations and red tape. However, there is no guarantee that the EU would not erect non-tariff barriers on certain goods under cover of not meeting EU health or safety standards. Those with long memories will recall the time when the French ordered all Japanese video recorders to be cleared through a single customs post in a small provincial town, pour encourager les autres.

Worse still, WTO rules do not cover services. Switzerland, which has no agreement with the EU covering financial services, is forced to set up subsidiaries of its banks in London, subject to all the EU regulations, to facilitate business in the EU. Further, the United Kingdom’s exit would end the European “passport” rights of asset managers and hedge funds working out of London and most likely would spell the recall of euro-related banking business back to the Eurozone, including clearing and processing. Frankfurt and Paris have long resented the dominance of London as the financial center for Europe, and the United Kingdom’s departure would present a golden opportunity for these cities to vie for the top spot. Former Bank of France governor and ECB vice president Christian Noyer is on record as saying, “if Britain left the EU, the euro area could no longer tolerate such a high proportion of financial activities taking place abroad.”

Budgetary Imbalance

London is also dominant within the UK economy and represents nearly a quarter of UK GDP. Financial services account for around 16% of office-based London jobs (not to mention legal, marketing, hospitality, real estate, and other finance-dependent activity) and pay much higher-than-average wages. So the loss to the economy from the hit to this sector could be substantial if a significant proportion of companies re-located to the Continent or other regions. Corporate tax and bank levy receipts from the financial services industry totaled over £10 billion in 2015, or 27% of corporate tax revenues. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, the total taxes paid by the financial sector (including taxes collected like employee income tax) were £66 billion in fiscal 2015, representing around 11% of total tax take. The knock-on effect on local real estate, dependent on high-paying finance jobs and companies, would also be noticeable, although some might welcome the greater affordability for non-finance-related locals and young people.

Source: UK Office for National Statistics.

Notes: When using the production or income approaches to estimate GDP, the contribution to the economy of each industry or

sector is measured using gross value added. Data for 2014 gross value added are annual, based on regional reporting as of

10 December 2015, and subject to revision. Extra-Regio comprises compensation of employees, holding gains, and grosstrading

profits which cannot be assigned to specific regions.

The Leave campaign points to the net annual contribution made by the United Kingdom to the EU budget that would be saved. While a precise figure is hard to pin down given all the rebates and reverse grants from the EU to poor regions of the United Kingdom, most commentators agree that the net figure is between £6 billion and £10 billion that would be saved each year. That’s about 0.5% of GDP. Would this money be saved? The government would likely be pressured to spend some money to compensate big exporters for loss of business, and some continuing budgetary contribution to the EU could be a condition of continued access.

The budget could also take a hit if people, not just businesses, leave. Some calculations show that the net influx of migrants into the United Kingdom has contributed around £20 billion to the UK exchequer over the years 2001–11. Although it is unlikely that current EU residents in the United Kingdom would be asked to leave, they could choose to (rumors of many French nationals resident in the United Kingdom applying for British citizenship have yet to be substantiated).

The United Kingdom’s Office of Budgetary Responsibility calculates that every 0.8% fall in GDP results in a £10 billion increased borrowing requirement (public deficit), so it would not take much of a hit to growth to wipe out the prospective budgetary savings in the short term. On the other hand, research firm Capital Economics believes that the impact of the 100 most costly EU regulations on UK business is of the order of £33 billion per annum.

Knock-on Effects

Real estate and foreign direct investment (FDI) would also probably suffer from Brexit. The EU accounted for around 46% of the stock of FDI in the United Kingdom in 2013. In 2014, the United Kingdom attracted 28% of the flow of all FDI into the EU. Beyond this, many non-EU countries use the United Kingdom as a gateway to Europe, with around 40% of the world’s top companies using London as their European headquarters, based on 2014 data from Blackrock Investment Institute.[1]See, for example, Christian Dustmann and Tommaso Frattini, “The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK,” The Economic Journal 124, no. 580, (2014): 593–643. Whether these companies stay would likely become contingent on the United Kingdom’s success or otherwise negotiating continued access to the EU post exit.

How Bad Could It Be?

Were voters to choose an exit on 23 June, the EU would have little incentive to cut the United Kingdom a sweet deal as it would want to discourage any others from following in its footsteps. For the United Kingdom, an exit could create a stagflationary environment in the short run as sterling fell, real estate fell, credit spreads widened, and jobs were lost (except, of course, the legal profession which would be kept busy unraveling four decades of union). The Bank of England would likely provide unlimited liquidity and potentially revive quantitative easing to help finance the budget deficit, while the current account deficit would shrink. Large-cap UK equities would benefit from being denominated in a devalued currency. It would probably take the full two years for the long-term consequences to become apparent.

For the rump EU in the case of a Brexit, risks of instability could rise if the UK’s exit turned out to be, at worst, neutral. Those on the Continent that have become critical of the EU’s apparent inability to deliver jobs and rising growth and question the price being paid to maintain the euro could be emboldened to join the various populist parties that point the finger at Brussels. It would also tilt the EU away from the free market and encourage heavier regulation of the financial sector. In the short term, sales of German luxury car makesr could be impacted by any pressure on jobs and compensation in the city’s finance industry, and the euro could come under pressure, though to a lesser extent than sterling, but is far from clear what the net effect on continental European equities would be after the United Kingdom’s exit.

The Bottom Line

It is possible that the United Kingdom could reinvent itself as a small but more nimble trading nation, crafting deals with more countries around the globe and rebalancing away from its dependence on financial services. It may also benefit from distancing itself from the EU if the Eurozone comes under further stress due to the use of a common currency and political infighting triggered by continued stagnation. The fact is, these are judgments no one can make with any confidence now. With the UK economy performing respectably, voters may be less likely to decide to rock the boat and go for the risky unknown. But if they did, such a surprise outcome would probably trigger the resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron and reopen the wounds of the Scottish independence referendum given Scotland’s staunch pro-EU stance. Investors with substantial exposures to British assets would do well to pay attention to sentiment ahead of the referendum, and, as suggested, sterling-based investors might lock in some currency gains ahead of the referendum if the USD/GBP exchange rate dips below recent lows around $1.38, though the odds of Brexit remain relatively low.

Stephen Saint-Leger, Managing Director

Stuart Brown, Investment Associate

Footnotes