US municipal bonds remain attractive and we advise maintaining allocations

- In the current low interest rate/low inflation environment, municipal bonds offer more attractive after-tax yields than US Treasuries and reasonable stability/liquidity versus zero-yielding cash.

- Municipal bonds provide stability during periods of market volatility such as January 2016.

- Overall, municipal bond fundamentals remain stable and high-quality issuers are able to pay their obligations. Significant issue-specific challenges exist in California, Illinois, and Puerto Rico.

- Maintain high-quality focus to avoid problem issuers, and underweight high-yield municipals in core municipal bond mandates.

Please see Eric Winig, “Municipal Bonds: Incredibly Low Yields, But Few Attractive Alternatives,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, February 2015.

About a year ago we penned a decidedly unexciting piece on US municipal bonds, advising investors to maintain allocations despite historically low yields. This has proved out for the moment, as ten-year munis have returned 3.2% for the 12 months since that paper—about 5.7% on a tax-equivalent basis—with coupon income offsetting a modest rise in yields. This compares to a pre-tax return of -0.7% on ten-year US Treasuries.

Today our advice is . . . much the same. Yields of around 2% look reasonably attractive given the alternatives—e.g., ten-year Treasuries with similar yields and richly valued equities—not to mention growing worries about the health of the global economy. January’s market action showed that investor behavior hasn’t much changed; jittery investors still send stocks down and bonds up, with munis returning 1.2% for the month and US equities, -5.0%.

The well-known troubles in the muni sector, while real, are also mostly localized, and should be easily avoided by active managers focused on high-quality issues. Further, while some recent court decisions may be problematic for muni holders down the road, they pose little risk in the short to medium term. The technical supports cited in our last piece—solid fund flows and limited issuance—also remain in place, although to a lesser degree.

In sum, while it is difficult to get excited about any asset class with a low-single-digit yield, munis remain attractive at current levels due both to the lack of alternatives and the risk that economic growth continues to sputter. High-profile issues such as the ongoing Puerto Rico default threat and underfunded pensions in states such as California and Illinois should not be minimized, but in our opinion pose little risk to investors, particularly those that, as we strongly advise, use active managers that focus on quality.

Revenge of the . . . 2%?

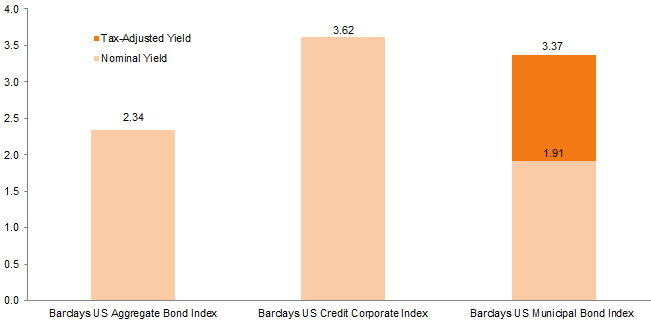

As shown in Figure 1, ten-year muni yields have been stuck around the 2% level since early 2012—with the brief, violent exception of the 2013 “taper tantrum”—and have moved in virtual lockstep with Treasuries for much of that time. Thus, the ratio of muni yields to Treasury yields has also stayed in a narrow range. Of course, most investors purchase munis at least partly for their tax advantages, and here they retain their advantage over Treasuries, while tax-equivalent yields are similar to those of corporate bonds (Figure 2).

Sources: Barclays and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Source: Barclays.

Note: The tax-adjusted yield takes into account the tax benefits for the highest tax bracket at the new maximum rate of 43.4%, which includes the Medicare surtax.

It is true that munis have disadvantages to Treasuries. Markets are far less liquid, particularly for smaller issues, and munis are not only less likely than Treasuries to benefit from a “flight to safety” in a risk-off scenario, but could actually suffer—as in 2008—if investors begin to worry about creditworthiness amid a financial or economic crisis. Most notably, states and municipalities cannot simply print new currency to pay claims, as can the US government; thus, as evidenced by recent troubles in Puerto Rico and Detroit, bankruptcy remains a tangible risk.

Such worries are exacerbated by the growing gap between state and municipal pension assets, and promised payments to retirees. According to The Pew Charitable Trusts, this gap has now surpassed $1 trillion, and there is little relief on the horizon. As Pew drily notes, “Many states have enacted reforms in recent years and have benefited from strong investment returns. But investment returns are uncertain, and government sponsors in many states have continued to fall short of making recommended contributions.”

Indeed, even places that have tried to address the issue have often found themselves stymied by legal restrictions. Illinois, for example, passed extensive reforms in 2013 only to have them struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court, while the Oregon Supreme Court recently ruled that the state was not permitted to reduce annual cost-of-living adjustments to retiree pensions.

However, while such worries are certainly an issue for muni holders over the long term, they are in most cases unlikely to affect muni bond payments over the short to medium term, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Illinois). Further, given the covenants of most muni issues, as well as the proclivities of most politicians, taxpayers are likely to bear the brunt of underfunding problems well before they filter down to muni holders.

This is one of a couple of reasons we strongly recommend active management in this area. Given that problems are focused in a handful of issuers and have been widely publicized, active managers that focus on quality should have little trouble avoiding these landmines;[1]Active managers that bought Puerto Rican debt in the thus far mistaken assumption that the island would eventually be bailed out, by contrast, were (and still are) speculating on a very uncertain … Continue reading this is of course not true of passive strategies. Active managers also tend to adjust duration as valuations shift; many are currently employing a “barbell” strategy, for example, to avoid the expensive two- to five-year part of the curve.

Winning on a Technicality

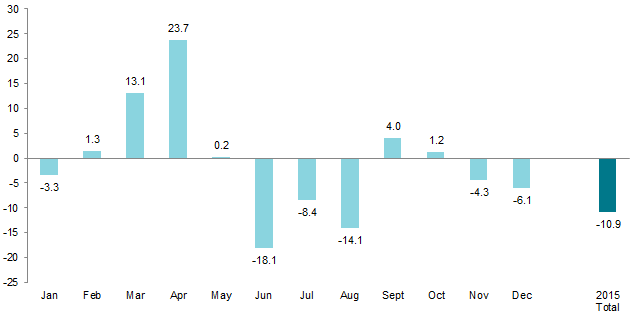

Market technicals, meanwhile, remain generally supportive. As shown in Figure 3, the volume of new issues remains low, as the majority of issuance continues to be used to refinance existing issues. Indeed, while total issuance for 2015 was the fourth highest in history, net issuance was actually negative (Figure 4). Wall Street estimates 2016 net issuance will be somewhere between $45 billion and $100 billion—due in part to an expected increase in issuance tied to infrastructure projects—as refinancing is expected to shrink to 55% of total issuance, from 62% in 2015. Still, as Morgan Stanley’s Michael Zezas recently told Bloomberg, the net issuance number “sounds large compared to what we just experienced, but in the entire history of the muni market, it’s not a number that is indigestible.” We agree.

Source: Sifma.

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

Note: The net volume of municipal bonds issued is calculated by subtracting the sum of the maturing/matured bonds and announced calls from the newly issued bonds over the course of each month.

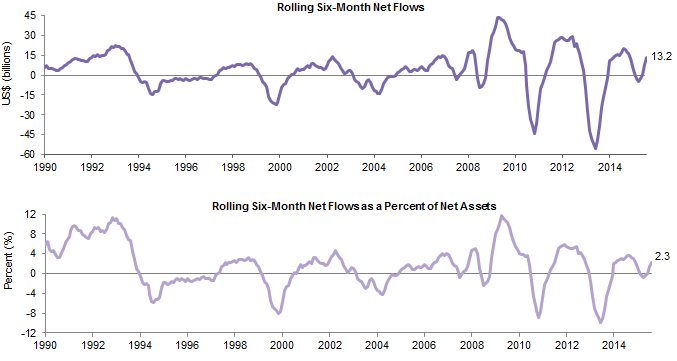

Sources: Investment Company Institute and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: The denominator of the flows as a percentage of net assets calculation is the asset level at the beginning of the six-month measurement period. Data for January 2016 have been estimated using weekly flows from the Investment Company Institute.

Fund flows are also still positive (Figure 5) and appear to be picking up as market turmoil increases; as of February 17, Lipper reported 19 straight weeks of inflows. If nothing else, generally solid flows in recent years indicate 2% yields are not in and of themselves enough to frighten off investors.

What Could Change Our View?

Last year, we cited five main potential worries for muni investors: higher-than-expected inflation, stronger-than-expected economic growth, accelerating pension problems, a deflationary downturn, and falling investor appetite for munis. None appear a clear and present danger—although one could make a case for building deflationary pressures—but of course things can and do change quickly, and buyers of such low-yielding assets have little margin of safety. Thus, muni holders should be attuned to anything that suggests the environment has materially changed (e.g., a sharp rise in Treasury yields and/or economic growth, a series of unexpected bankruptcies, or a court ruling throwing muni covenants into question) and should be prepared to act accordingly.

That said, we also continue to believe, as we said last year, that any negative news surrounding specific high-profile issues—e.g., Puerto Rican debt—could create a buying opportunity if it (a) is truly a localized event, and (b) causes a general sell-off in munis.

Conclusion

Had someone told us ten years ago (or even five) that we would advocate buying municipal debt with yields hovering right around 2%, we would have found that hard to believe. And we are certainly cognizant of dangers of reaching for yield.

That said, the goal of a high-quality buy and hold municipal bond allocation is to earn moderately attractive after-tax yield with modest mark-to-market volatility, and very low principal/default risk.

This, combined with the lack of alternatives, the low/zero inflation world in which we find ourselves, and the happy combination of low supply and solid demand, causes us to view munis as at least reasonably attractive at current levels, and we advise investors to maintain allocations.

Eric Winig, Managing Director

Robert Roche, Investment Associate

Footnotes