Currently, there is an active debate about whether the United States is in a recession. Two quarters of negative GDP fits one definition of a recession; however, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) looks at a greater expanse of data before making its assessment. We will examine some of this data and dig into other line items in the national accounts to further our understanding. We will also look at historical trends in employment around recessions to put today’s labor market in context.

National Accounts

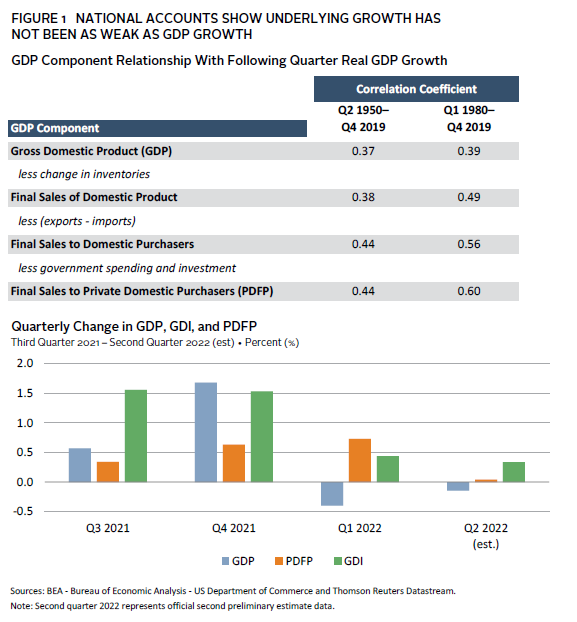

There is no doubt that the United States has entered what is sometimes termed a “technical recession,” with GDP having declined in each of the past two quarters. However, the first quarter appears less recession-like when examining the details of the national accounts (Figure 1). First, gross domestic income (GDI)—an alternative measure of economic activity—expanded at a moderate 0.4%, or 1.8% on an annualized basis. In theory, the income and expenditure (i.e., production, as in GDP) methods of measuring economic activity should match exactly, which they effectively do over long horizons. In practice, however, they vary, particularly over short horizons. This is because they are derived from different sources and there are some coverage differences, as well as timing differences between when incomes and expenditures are recorded.

The components of the GDP release also indicate that drags on growth in the first quarter were primarily contained to elements that are to varying extents exogenous to underlying economic activity in the United States. In the first quarter, this was chiefly trade, with smaller drags from fiscal policy and inventory changes. Final sales to private domestic producers (PDFP) strips these components from GDP, leaving us with domestic private consumption and investment, the core driver of the economy. Illustrating this, PDFP is a better predictor of next-quarter GDP growth than the GDP figures themselves. In the first quarter, PDFP expanded by a healthy 0.7%, or 3.0% annualized (Figure 1).

The details provided by the national accounts for first quarter 2022 therefore do not paint as bleak a picture as suggested solely by GDP, but the second quarter is somewhat different. In addition to the negative reading on GDP growth, PDFP growth slowed to an effective standstill, indicating that growth in underlying domestic economic activity had, in fact, slowed meaningfully. However, GDI continued to expand in second quarter 2022, albeit at a slowing rate, growing by 0.3% during the quarter. The divergence between GDP and GDI in recent quarters has now seen the deviation between the two reach the largest it has ever been as a percentage of GDP. Nonetheless, it seems reasonable to conclude that there was a genuine slowing of economic growth in the second quarter. Whether this meets the NBER threshold is another matter.

National Bureau of Economic Research

The NBER’s traditional definition of a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” Their judgement is based on three criteria: depth, diffusion, and duration. These are somewhat interchangeable, in the sense that while the NBER looks to have each criterion met, there are certain instances when an extreme reading on one criterion may offset weaker indications from another. The March/April 2020 recession is an example of this when the extreme depth and diffusion of activity decline were sufficient to declare a recession despite its short duration.

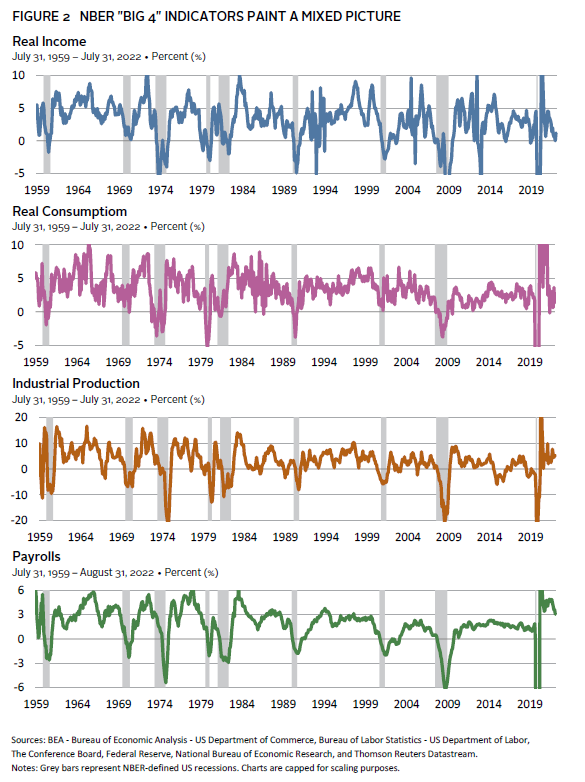

It is thought that the NBER focuses on four main indicators—real income, real consumption, industrial production, payrolls—that represent different aspects of the economy (Figure 2). Looking at the six-month annualized percentage change in each of these, we can see that, historically, growth in each indicator slowed sharply into every recession, then turned negative at some stage during every recession, with only two exceptions (real income from December 1969 to November 1970, and real consumption from March 2001 to November 2001). Looking at these indicators now presents something of a mixed picture, although on balance they depict a weakening environment. Payrolls remain the strong piece of the picture, as it continues to grow well above trend. Real income, by contrast, is the weakest link, with growth having essentially flatlined in the six months ended June 30, though there was a slight uptick in July. Real consumption is expanding well below its long-run average and the three-month growth rate is approaching zero. Industrial production is somewhere in between. The six-month annualized growth rate of 5.3% still looks more than solid; however, it is slowing, with the three-month annualized growth rate now just under 2%, which is below its historical average.

Employment

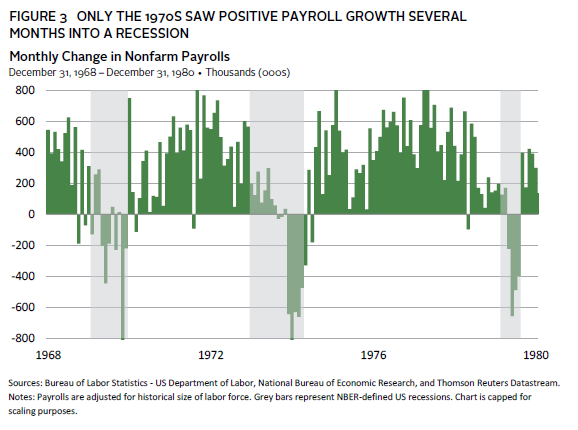

With payroll growth so strong, a common question is whether it is possible to be in a recession in such an environment. The record shows that it is not uncommon for the early months of a recession to exhibit positive payroll growth; however, it is rare for strong positive growth to persist several months into a recession (Figure 3). The 1970s proved to be the exception to this, particularly during the recession from November 1973 to March 1975. Inflation is, of course, a parallel between that period and the present day. It is conceivable that the dichotomy between nominal and real growth during these periods contributes to the ability of employment growth to be positive, even as a recession commences.

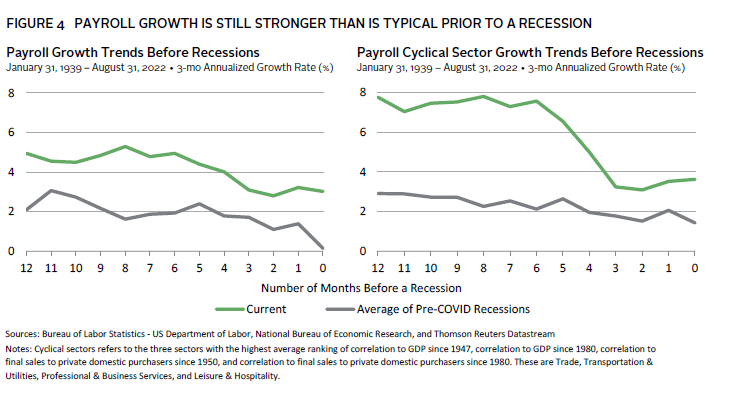

Prior to a recession, the slowing trend in payroll growth is noticeable, if not quite monotonic (Figure 4). Growth in payrolls has indeed slowed over the last year, though the growth rate still remains well above that of the prelude to the average recession, as well as above its long-term average. Looking at just the most cyclical sectors of the employment market, we can see that the slowdown in growth in recent months has been more precipitous. Still, as is the case with total payrolls, the current three-month annualized growth rate remains above the pre-recession average and above its own long-term average. With unemployment as low as it is, it’s unlikely that jobs growth can continue at its recent pace for much longer. However, the labor force participation rate still stands below pre-COVID-19 levels. This potentially extends the runway for positive employment growth, as more people may yet return to the labor force.

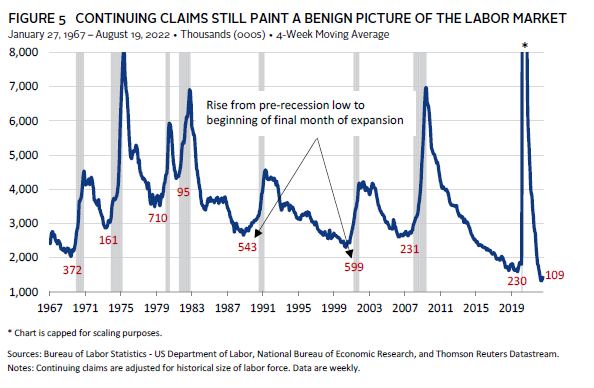

The rise in initial jobless claims, which bottomed in early April on a trailing four-week average basis, has raised some alarm that the labor market may be weakening. However, looking at continuing claims provides some comfort. While the trailing four-week average of this metric has ticked up since mid-June, it remains close to its lows and still lower than at any time pre-COVID-19 relative to the size of the labor force. The rise of 109,000 in continuing claims from its mid-June low is lower than the labor force–adjusted rise seen in the run-up to any prior recession bar that of 1981–82, and much lower than the pre-recession average of 368,000. The absolute level of continuing claims also remains close to a historic low. Therefore, the rise in initial claims may signify some marginal weakness in one or more portions of the labor market; however, in aggregate, the market remains strong enough to reabsorb most of these claims (Figure 5).

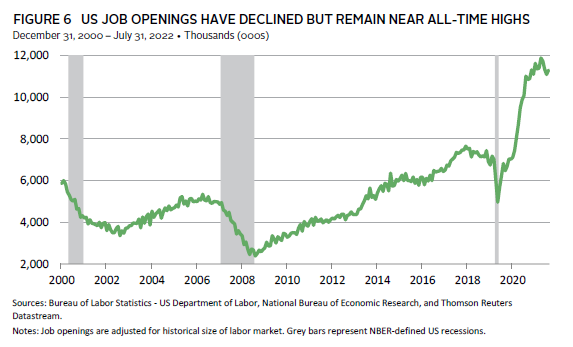

Job openings are one of the final pieces of the jigsaw. Whether your take on the job openings data is optimistic or pessimistic depends on whether you put more store in levels or changes. The level of job openings remains relatively close to an all-time high and still greater by some margin than at any time pre-COVID-19 (Figure 6). This is a positive sign for the labor market to the extent that the level of openings in this ballpark is real and persistent. However, openings have fallen since their March peak, and the fall in that time is already comparable to that witnessed from the pre–Global Financial Crisis and pre-COVID-19 peaks to immediately prior to the onset of those recessions.

Conclusion

In sum, there are a few amber warning signs in the labor market, but the preponderance of data still points to a strong employment environment. When these data are taken in conjunction with those from the national accounts and the NBER’s “Big 4” data points, it seems unlikely that the US economy was in a recession in first quarter 2022, though real income and real consumption were showing weakness. Second quarter 2022 remains more of an open debate, with the flatlining of PDFP, continued sluggishness of real income and consumption, slowing growth in industrial production, and softening job openings building a somewhat stronger case.

Thomas O’Mahony

Investment Director, Capital Markets Research