Following a more gradual climb in first half 2018, US equities appreciated materially in third quarter, ending September just off record highs set in the prior weeks. The S&P 500 Index returned 7.7% in third quarter and 10.6% year-to-date; by comparison, the Russell 2000® Index returned 3.6% and 11.5%, respectively. All Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) sectors gained in third quarter, led by health care, industrials, communications services,[1]On September 24, 2018, S&P Dow Jones implemented a significant reclassification of the GICS sectors in its equity indexes; the former telecommunications services sector was rebranded as the … Continue reading and information technology. International equity markets had mixed results last quarter: Europe’s STOXX 600 Index returned 0.7%, while the MSCI Emerging Markets Index returned -1.1%.

Hedge funds also produced positive results for third quarter, but gave back some of the alpha they had generated in the first half of the year. The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index returned 0.6%; the HFRI Equity Hedge Index, 0.5%; and the HFRI Event Driven Index, 0.8%. The HFRI Macro (Total) Index was flat for third quarter.

In this quarter’s update, we highlight a strategy that has been out of favor in recent years: discretionary global macro. This strategy attracted investors after it performed well in relative terms through the global financial crisis; the HFRI Macro: Discretionary Thematic Index returned -12.1% in 2008, 14.5% in 2009, and 5.5% in 2010. Since then, however, the index has been virtually flat through third quarter 2018. Below, we review some possible explanations for the strategy’s underperformance since 2011, and discuss why it could soon become more compelling.

Discretionary Global Macro

In the 1990s and 2000s, discretionary global macro managers’ investor bases were dominated by wealthy individuals and families seeking higher risk/return strategies. Conversely, much of the capital that flooded discretionary global macro managers after the crisis came from large pools of institutional investors expecting modest volatility they had grown accustomed to experiencing in other hedge fund strategies. In response to this shift, many managers adjusted their business models: instead of having a single chief investment officer individually managing the strategy or a small group of portfolio managers (PMs) sharing oversight, they adopted a multi-manager model in which individual PMs managed discreet sleeves of the overall strategy, often with each sleeve using the PM’s preferred trading approach and investing across a subset of the asset classes traded in the overall strategy. As a result, some larger managers went on a PM-hiring binge, many of them growing their ranks to 30 or more. These structural changes allowed discretionary global macro firms to manage more assets while spreading the risk across a number of individual PMs and sub-strategies.

Many of these newly expanded firms introduced strict risk-management rules for their PMs, to significantly reduce the prospect of large drawdowns. Firms implemented “down-and-out” rules, setting drawdown thresholds at which PMs would either forfeit some of their capital or be dismissed. Newly hired PMs faced with these drawdown limits at the outset reduced their risk profiles, which in turn lowered ex post fund-level volatility.

Through these changes, many managers accomplished their mission of gathering more assets while reducing volatility. However, this outcome came at the expense of realized performance for their investors. As a result, knowingly or unknowingly, discretionary global macro managers chose asset growth and business stability over capital appreciation. Meanwhile, their fees remained among the highest in the hedge fund industry; some managers charged up to a 3% management fee and a 30% incentive fee. Less risk-taking led to higher fees per unit of risk taken, and thus fees have consumed a large portion of the profits that macro hedge funds have generated since 2011.

Many newly hired PMs in the discretionary macro space focused on trading interest rates. It made perfect business sense to invest recently raised capital in the global fixed income markets, given their massive size and the fact that, historically, there had been enough volatility in global interest rates to generate attractive returns. However, after the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis, the major developed economy central banks uniformly pursued a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), or eventually in some cases a negative interest rate policy (NIRP). As a result, short-term rates in the United States, Europe, and Japan were effectively anchored at or near the zero bound, and for several years longer than most market participants anticipated. Combined with the central banks’ massive quantitative easing programs, fixed income market volatility became negligible, resulting in fewer money-making opportunities. ZIRP and NIRP also eliminated profits on unencumbered cash—a large, often-overlooked source of return for discretionary global macro managers (and for hedge fund strategies overall).

Today, however, most of the pressures cited above have been reversed or alleviated. Over the last 18 months, most macro managers have experienced substantial AUM declines after producing mediocre returns for several years in a row, and many have shut down. Those that survived have reverted from their large, multi-manager structures to their former model of concentrating risk-taking among small groups of PMs managing a single strategy as a team. The combination of this more recent evolution and smaller asset bases has increased risk-taking and improved performance. The asset base retrenchment has also caused discretionary global macro managers to meaningfully cut fees, bringing them more in line with other hedge fund strategies.

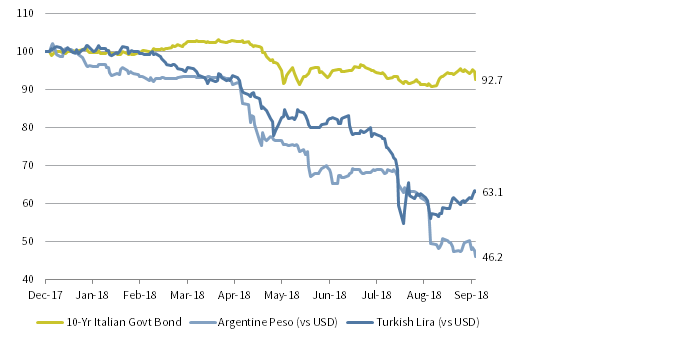

Alongside these positive structural changes, global monetary policy is finally diverging. The Federal Reserve is raising interest rates and reducing the size of its balance sheet, and the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of Canada have also begun slowly normalizing their policy rates. Although the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have dialed back their quantitative easing, they continue to retain their highly accommodative monetary policies stances. This divergence has increased volatility in both developed and emerging fixed income and foreign exchange markets— examples include Italian government bonds, the Argentine peso, and the Turkish lira (see figure below)—which in turn should increase profit-making potential for discretionary global macro managers.

YTD PERFORMANCE OF ITALIAN GOVERNMENT BONDS, ARGENTINE PESO, AND TURKISH LIRA

December 31, 2017 – September 30, 2018 • Cumulative Wealth • December 31, 2017 = 100

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: All data are daily. Italian bonds are represented by the Datastream Italy 10-Year Benchmark Government Bond Clean Price Index.

Eric Costa, Managing Director

Max Jallits, Investment Director

Footnotes