The strains on public universities require a new approach to resources, and an increasingly expertly managed endowment fund and fundraising operation are essential to that evolution

- The combination of flat or declining net tuition growth and declining state appropriations has created a revenue gap for public universities. Endowment assets and gifts are significant components of the financial equation; however, most public universities are not yet optimally structured to realize their potential in these areas.

- Multiple, separately managed endowments supporting one university is a suboptimal business model. Similarly, decentralized fundraising models face risks of redundant outreach efforts that lead to donor fatigue, multiple asks, and missed opportunities.

- Consolidating to one endowment portfolio and a single entity for conducting fundraising activities creates a more focused approach where all resources are pulled together to optimize fundraising and endowment management efforts.

The majority of US colleges and universities, public and private, are stressed by flat or declining net tuition growth. Public universities face the additional challenge of declining state support, which has historically been a large part of total revenues. To fill the gap, public universities must turn to a funding model that looks more like that of their private counterparts, where support from endowment assets and gifts is the major focus for growing revenues.

Are public universities operating in a “new normal,” and do they have the appropriate models for endowment management and fundraising to steward effectively and continue to grow crucial resources? To help answer this question, Cambridge Associates reviewed data from over 190 US colleges and universities and supplemented this information with a survey of 22 leading public universities as well as interviews and a roundtable discussion with trustees of flagship universities, university systems, and affiliated foundations. This research note shares our observations from this analysis and our recommendation that public universities consider the benefits of a consolidated approach to endowment management and fundraising as endowment assets and gifts grow in importance.

The Stressed Public Higher Education Funding Model

The public university business model continues to face financial headwinds. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,[1]Michael Mitchell, Vincent Palacious, and Michael Leachman, “States Are Still Funding Higher Education Below Pre-Recession Levels,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 1, 2014. on a real (inflation-adjusted) basis:

- All states except Alaska and North Dakota are spending less per student than they did before the recession.

- State appropriations for higher education are down 17.5% since the recession.

- Average state spending per student is down 23% compared to pre-recession levels.

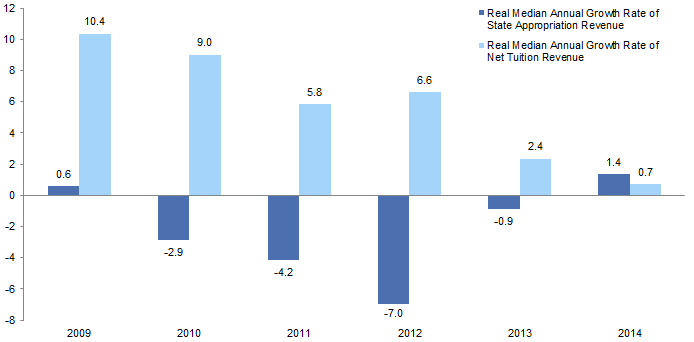

The decline in state funding for higher education has placed greater pressure on tuition revenue to balance university budgets. Real state appropriation funding declined 13% from 2008 to 2014, while public university median net tuition revenue grew by nearly 35% in real terms (Figure 1).

Source: Moody’s MFRA database.

Note: Includes 191 public universities that had data available each year from 2009 to 2014.

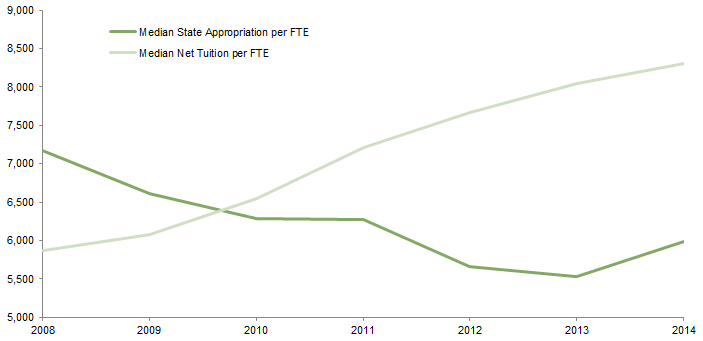

Net tuition revenue growth was robust in the years immediately following the 2008–09 global financial crisis, as student demand for higher education remained strong. However, net tuition growth has decelerated steadily since 2012, a result of tuition pricing and financial aid commitments, which can further erode net tuition revenues (tuition revenue less financial aid). As a percentage of total revenues, median net tuition per full-time equivalent (FTE) student eclipsed state appropriations per student in the public university business model starting in 2010 and has continued to grow (Figure 2).

Source: Moody’s MFRA database.

Note: Includes 190 public universities that had data available each year from 2008 to 2014.

Even as net tuition has become a larger percentage of total revenue, future growth is limited by competition and pricing pressures. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, real median household income declined in the United States by nearly 5% from 2008 through 2013, constraining families’ ability to pay rising tuition prices. Further, media and public scrutiny of tuition prices has placed pressure on state lawmakers to keep public higher education affordable by limiting the growth of, or even freezing, tuition rates. Several states link appropriation funding to tuition price limits. Given constraints on in-state tuition rates,[2]“Trends in College Pricing,” The College Board, 2014. On average, national public four-year, in-state tuition and fee prices increased 1% over the past year and 18% in the past five years, when … Continue reading many public universities have grown net tuition by enrolling more out-of-state and international students who pay higher tuition than in-state students.

Minding the Gap

This confluence of financial pressures has shifted the public university funding model in a very short time period. With traditionally relied-upon sources of revenue less available, public universities must seek to diversify their revenue streams to fill the gaps, with endowment assets and gifts increasingly prominent sources of revenue.

Endowment support of the operating budget, otherwise known as “endowment dependence,” measures the role of the portfolio as a revenue source for the enterprise. Traditionally, endowment dependence for public universities has been lower than their private counterparts—just 2.8% compared to 15.1%, respectively, in 2014, according to our Annual Analysis of College and University Investment Pool Returns report. As the higher education landscape continues to shift and traditional revenue sources have limited growth potential, endowment dependence for public universities could increase substantially, placing endowment portfolios in a larger and more significant role in funding university operations. Do public universities have the right models for endowment management and fundraising to grow these assets and their role in the enterprise?

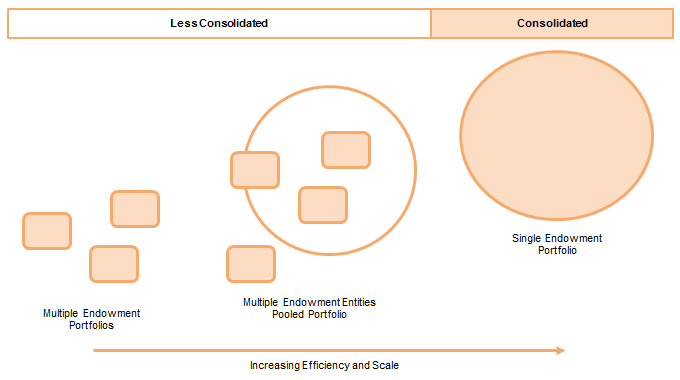

Current Models for Endowment Structure and Management. In our study, public university endowments reported three types of endowment structures:

- Multiple endowment portfolios managed by separate entities;

- Multiple portfolios that have been partially pooled in a unitized investment portfolio managed by a single entity, or

- A single endowment portfolio managed by a single entity.

Smaller, separately managed endowments can face greater limitations and inefficiencies than a single, large pool of assets. Larger portfolios have the scale to invest across a wider range of alternative asset classes, often at lower fees. Some institutions with disparately managed funds indicated that they hope to achieve more centralized investment management in a unitized investment pool where separate owners (university, university system, university-affiliated foundation, and/or various schools and centers within the university) can own their assets while pooling their invested assets for better investment opportunities. Some institutions are formalizing this approach with comprehensive agreements, while others are introducing this as an optional offering. For example, one university system is offering investment management services to the smaller foundations supporting the university campuses. Some institutions with smaller endowments described the challenges of consolidation, as they risk alienating donors and the trustees who oversee these pools, who are engaged with the smaller entity via their involvement in the endowment.

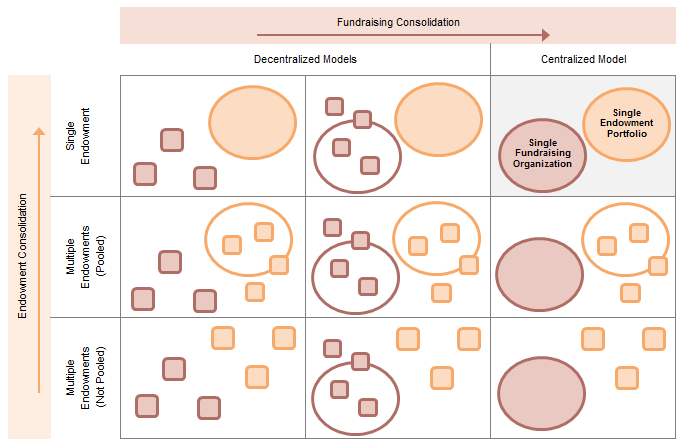

We think of the endowment management collaboration as following along a continuum of consolidation, as noted by the arrow in Figure 3.

Source: Moody’s MFRA database.

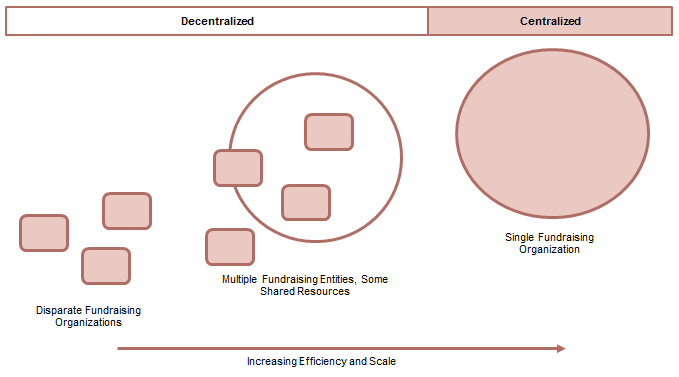

Current Models for Fundraising. Institutions in our survey described two types of fundraising models: decentralized and centralized. The majority of public universities in our study have a decentralized model where multiple entities—for example, university development and the alumni association—raise money for the university. Within the decentralized model some institutions reported that multiple fundraising entities are completely separate, while others reported that the groups share resources, such as databases, research, and gift accounting. Approximately one-third of the public universities in our study have one centralized fundraising operation that resides either at the university or a university-affiliated foundation.

In most of the decentralized fundraising models, both the university and university-affiliated foundation conduct fundraising activities. The remaining institutions with multiple fundraising entities reported a variety of combinations of the university campus(es), university system(s), and/or foundation(s) that conduct fundraising activities. Institutions with a centralized fundraising model consolidate fundraising staff and activities at a single organization and may oversee development professionals who work within different university divisions.

Fundraising for public universities can also be thought of as following along a continuum, as shown in Figure 4.

Source: Moody’s MFRA database.

Consolidation for Efficiency: Optimizing Portfolio Structure and Fundraising Efforts

An investment management model of multiple, separately managed endowments supporting one university is suboptimal. The simplest and most effective investment management model would be one endowment portfolio that supports the university into which all long-term funds can be directed. Pooled funds fall in the middle of this spectrum: multiple endowments may exist to support the university or system, but pooling them together allows for shared investment management access and streamlined investment oversight. Multiple endowments could potentially confuse donors with options, but, on the other hand, could also provide clear paths to align donations and donor interests.

Similarly, while decentralized fundraising models may benefit from the efforts of multiple stakeholders charged with raising money for the university, they face additional challenges as they try to harness energy across organizations to coordinate fundraising efforts for the university. When entities are uncoordinated and not sharing information, they face risks of redundant outreach efforts that lead to donor fatigue, multiple asks, and missed opportunities. Centralized efforts enable efficiencies of scale with respect to resources such as research, mailing lists, donor assignments, and the university officers’ time and effort (president, provost, board chair, deans, etc.). The coordinated fundraising operation can also be more closely aligned with the university’s financial priorities, so capital expansion strategies consider the optimal mix of endowment, facilities, and operation resources that can best support the university’s goals. Disparate fundraising efforts may not align with institutional strategic planning, which may miss important opportunities to engage donors and to further institutional priorities.

Figure 5 puts the two coordination continuums together as we consider the pathway toward more cohesive and effective resource stewardship.

Source: Moody’s MFRA database.

Along the left-hand side, the level of endowment fund(s) consolidation moves upward from multiple, non-pooled endowment funds on the bottom to a single endowment fund on the top. Across the top, the level of fundraising collaboration moves rightward from the decentralized models to a centralized model. An institution in the bottom, left-hand corner of this matrix is challenged by disparate endowment funds and fundraising efforts, while an organization in the top right of this matrix operates in a more focused situation where all resources are pulled together to optimize fundraising and endowment management efforts. Moving toward this more effective model (highlighted in Figure 5) optimizes resources and a growing role for the endowment in the public university business model.

Conclusion

Historically, capital inflows (e.g., capital campaign proceeds) were intended for mission expansion either through expanded facilities or expanded programs. Today, endowment growth may also be essential to shore up the current mission and maintain the current operating scale. The strains on public universities require a new approach to resources, and an increasingly expertly managed endowment fund and fundraising operation are crucial to that evolution.

Net flow rate aggregates the (annual) rate of inflows to endowments and the (annual) rate of outflows from the endowment to show the net change to the endowment (excluding investment returns). To learn more about this concept, please see Ann Bennett Spence et al., “The Missing Metric for Endowment Growth: Net Flow Rate,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, November 2014.

Takeaways and next steps for public universities seeking to pursue this approach include:

- The most successful university fundraising operations provide clear opportunities for donors to connect to their universities and support institutional priorities. Several institutions in our survey have centralized fundraising or intend to implement more coordinated approaches. The coordinated fundraising effort can be more aligned with university needs and donors’ interests.

- Endowments built through strong investment performance and careful management of net flow grow the fastest.

- The most successful investment portfolios have a long-term horizon and a risk profile and investment composition that align with institutional goals and needs. Public university governance structure and practices must uphold these long-term goals and serve the institution beyond the current stakeholders.

As public universities transition to operating under the “new normal” environment of uncertain growth in public funding and net tuition revenue, the endowment portfolio will increasingly be asked to contribute a higher proportion of operating revenues and balance sheet health. The institutions that emerge from these challenges in good health will be buffered by cohesive fundraising efforts that cultivate new revenue, a strong culture of philanthropy, and effective governance and investment management that lead to endowment growth.

Tracy Filosa, Senior Investment Director

Grant Steele, Director

Geoffrey Bollier, Senior Investment Associate

Footnotes