Summary of Policy Benchmarking Approaches

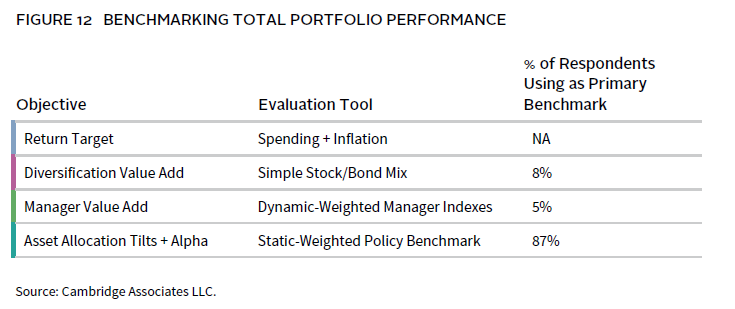

Benchmarking investment performance is an essential part of an institution’s well-functioning governance process. When selecting a benchmark, it is important for institutions to understand what types of questions they are seeking to answer (Figure 12). There is no single benchmark that can assess every aspect of portfolio management. Consequently, it is not uncommon for institutions to use multiple benchmarks in their performance evaluation process. In our survey, we asked respondents to provide both the real return objective for the investment portfolio and the primary benchmark used to evaluate investment performance at the total portfolio level.

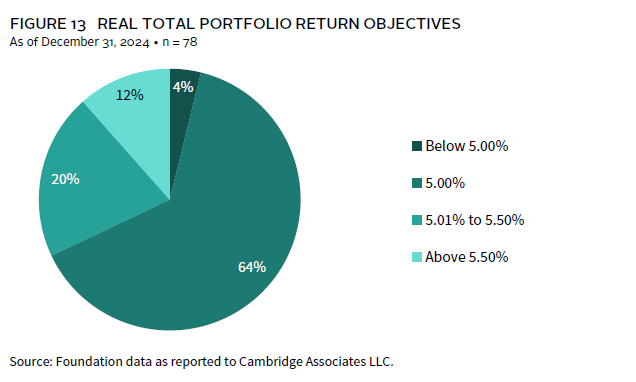

Most foundations in this study are private nonoperating foundations that are required by law to meet an annual payout requirement. These types of foundations must make qualifying distributions that amount to approximately 5% of their average total asset value across the tax year. Foundations that aim to preserve the purchasing power of their assets over time must earn a real return (i.e., adjusted for inflation) that at least matches their payout rate. Since investment returns are volatile from year to year, return objectives are evaluated from a long-term perspective as opposed to a goal that must be met every year. Given the payout requirement that most respondents are bound by, it is not surprising to see that nearly two-thirds (64%) reported that their long-term real return objective was 5% and another 32% have a return objective that is higher than 5% (Figure 13). The small percentage of respondents that reported a return objective below 5% consists of two private operating foundations and one community foundation.

In the investment returns section, we cited the performance of a blended index weighted 70% to the MSCI ACWI and 30% to the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index. For foundations that are diversified across alternative asset classes, this type of benchmark helps to evaluate whether the decision to diversify the portfolio added value. Our comparisons of median foundation performance versus the 70/30 benchmark show how the peer universe in general measured up to a simple, passive investment option.

In practice, just 8% of foundations reported that a simple blended index was the primary benchmark used for their total portfolio return. The most common approach among this subgroup was to use a blend weighted 70% to an equity component and 30% to a bond component. However, two foundations used a higher weighting for the equity index—80% was the highest reported—while one other respondent reported a weighting as low as 65%. The most appropriate weightings for this type of benchmark would be a blend that aligns with the targeted risk profile of the portfolio.

The remaining peers in the universe use a policy benchmark with three or more components. The vast majority (87%) use a blend of indexes with static weightings that align exactly or closely with the asset classes and target percentages specified in their asset allocation policies. This type of benchmark helps an institution evaluate how its portfolio performed relative to the blended index that represents its default or normative position. A handful of respondents (5%) use a blend of manager-specific indexes, where the weightings update frequently (e.g., monthly) to match each manager’s allocation in the portfolio. This type of benchmark is intended to focus on manager selection decisions and neutralizes the effects of over/underweights of the actual asset allocation versus policy targets. The figures that follow provide more detail on benchmarks for the foundations that use a dynamic-weighted or static-weighted policy benchmark.

Components of Policy Portfolio Benchmarks

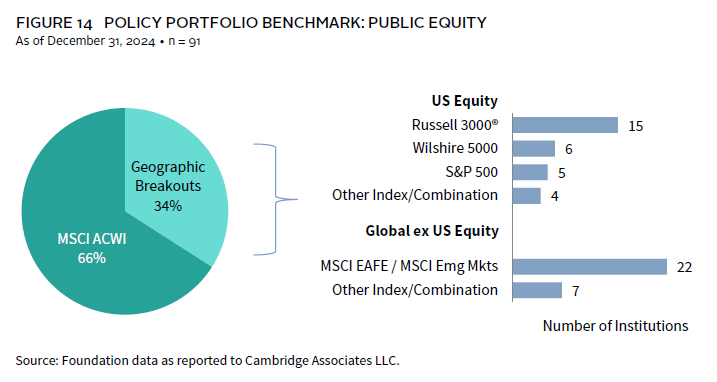

When it comes to benchmarking public equity, the use of the MSCI ACWI is as prevalent as ever. Last year, 58% of respondents used this index to represent their entire public equity allocation in the policy benchmark. This year, the percentage of respondents citing this index had increased to 66% (Figure 14). The remaining respondents use a combination of indexes that are more geographically defined. For those that use a US-focused benchmark, the Russell 3000® Index was by far the most common. For global ex US equities, a combination of the MSCI EAFE Index and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index was cited most often.

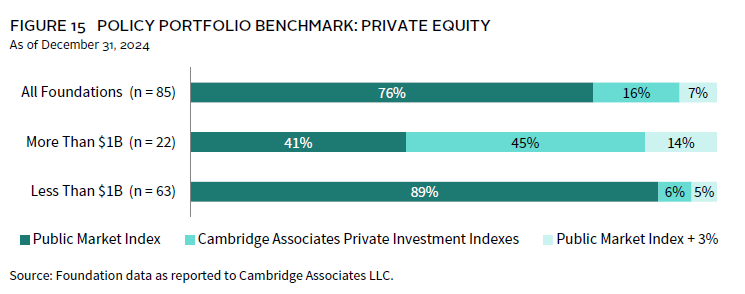

When evaluating PE/VC in the policy benchmark, 76% of respondents use a public index, with the MSCI ACWI being the most preferred index among this cohort (Figure 15). The rationale for using a public index was that the public equity bucket in the portfolio is the funding source for private equity allocations. And if the portfolio did not invest in private equity, that capital would have remained with the public equity allocation. The use of a public index primarily evaluates whether the decision to invest in private markets paid off for the portfolio.

There are some shortcomings to using a public index to benchmark private equities. Most notably, the public stock market is not a universe of securities that is representative of private equity investments. Consequently, in years such as 2024, which saw large differentials between public equity and private equity performance, the spread between the portfolio return and the benchmark return can be more reflective of those market dynamics than of how well the management team implemented the private portion of the portfolio. A smaller proportion of the universe (16%) instead used the CA private investment indexes to represent private equity in the policy benchmark. These indexes do not meet the ideal properties of benchmark as they are not transparent or investable. However, they are a universe of institutional-quality private investment funds that are more representative of the asset class compared to a public index. The remaining 7% used a public index plus a 3% premium, with the MSCI ACWI being the most common index in these situations.

There was a noticeable difference in the breakdown of responses by asset size. For foundations less than $1 billion, a public index was by far the most common practice. In contrast, approaches were more mixed among foundations more than $1 billion, with the CA private investment indexes being cited by almost half of respondents. The private investment indexes can be custom weighted by vintage year and exposure across different strategies, which helps to evaluate fund selection. It is likely for this reason that the approach continues to be prevalent among larger institutions, of which many have performance-based incentive compensation programs for their investment staff.

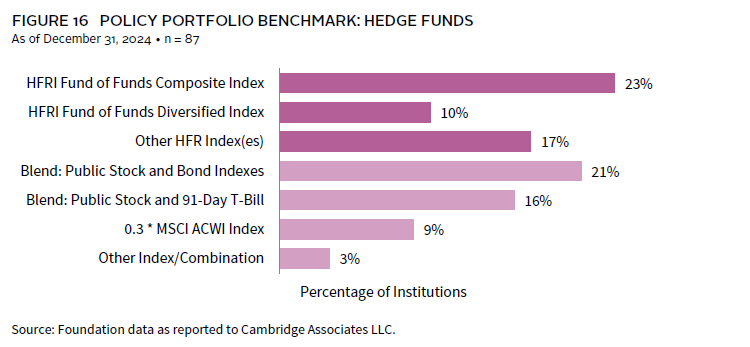

Investors also face similar challenges of selecting an appropriate index when accounting for hedge fund allocations in the policy benchmark. Approximately half of respondents use one or more indexes produced by HFR, which tracks hedge fund managers that report to their database (Figure 16). This is a lower percentage than last year, when 60% of foundations reported using HFR. The use of a beta-adjusted benchmark for hedge funds has become more common among foundations, although the exact method varies across a few different options.

For fixed income, 45% of foundations use the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index, which was almost the same result from last year’s survey. The remaining respondents chose from a number of other indexes that presumably are a fit for their underlying exposures. When it comes to real assets, benchmark choices are even more unique across the respondent group due to the variety of strategies in this bucket.

Value Add Versus the Policy Benchmark

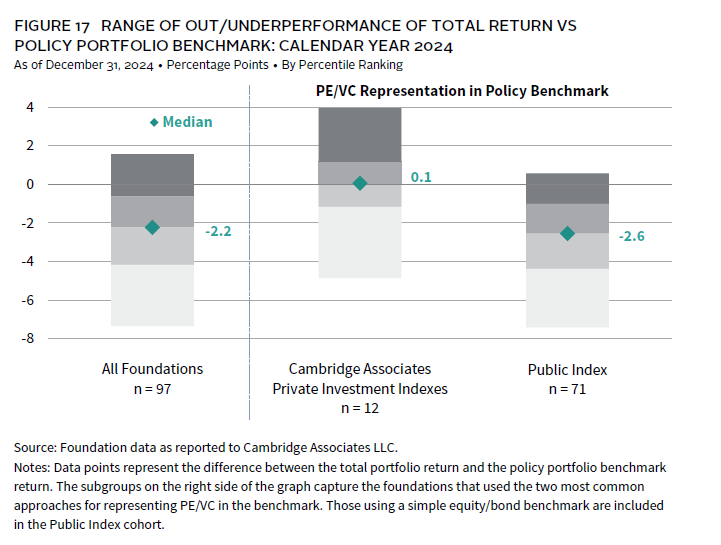

Most foundations fell short of their policy portfolio benchmark in 2024. Just 16% of respondents reported that their total portfolio return beat their benchmark for the one-year period. When considering the spread between the portfolio return and the benchmark, the median across the respondent group was -220 bps for the calendar year. Outcomes varied widely across foundations, ranging from 160 bps of outperformance at the top 5th percentile mark of the universe to underperformance of 740 bps at the bottom 5th percentile (Figure 17).

When breaking the peer universe down further, it is clear that the type of benchmark used for private equity was a big factor in how well an institution performed versus its overall policy benchmark in 2024. For foundations that used the CA private investment indexes, the median value add was actually positive at 10 bps. In contrast, the median value add for foundations using a public index was significantly lower at -260 bps. While there were not enough respondents using a public index plus a premium to show a percentile distribution for this cohort, these foundations typically underperformed by even larger margins because of the added return hurdle.

The different experiences of these subgroups tie back to the relationship between public equity and private equity returns in 2024. The one-year horizon IRR of the CA Private Equity and Venture Capital Index was significantly lower than the MSCI ACWI mPME (6% versus 18%). Therefore, an institution using the CA private equity indexes would calculate a lower benchmark return than it would if using a public index. The difference becomes even more magnified the higher a foundation’s allocation is to private investments. With most foundations in our universe having 20% or more of their portfolios invested in PE/VC, the index choice is consequential in the policy benchmark calculation.

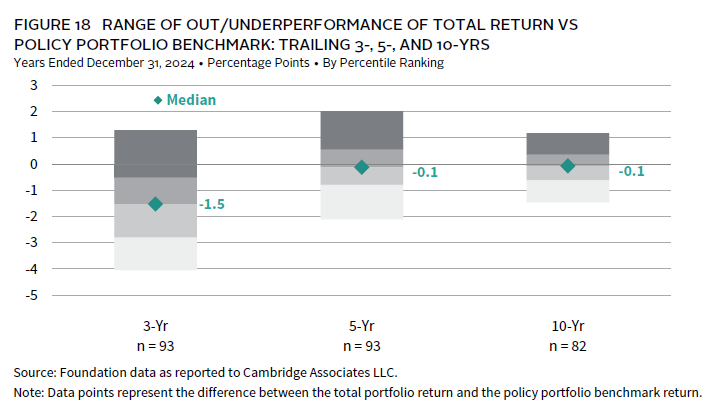

The different benchmarking approaches were not as impactful on the value-add statistics for the trailing three-year period (Figure 18). Part of that is because the public versus private index spreads were not as large for longer periods, and the differentials that do exist naturally get smaller in the annualized calculations. For the overall respondent group, the median spread between the portfolio return and the benchmark return was -150 bps for the trailing three-year period. Foundations did fare better over the longer term, with almost half of respondents outperforming their benchmarks over the trailing five-year and ten-year periods.