Executive Summary

- In an environment of low equity and bond returns, investors may again be looking to portable alpha as a possible solution. However, portable alpha is complex and comes with many risks, not the least of which is identifying the sources of alpha, as well as ensuring the liquidity of the alpha sources, monitoring for any beta embedded in the alpha sources, and managing the portfolio leverage.

- Portable alpha is a strategy that allows investors to combine the alpha from one investment with the beta from another. The use of derivatives permits investors to gain “synthetic” exposure to an investment, which allows the alpha and beta return streams to be separated and recombined. Investors have two main ways to craft a portable alpha position: (1) adding pure alpha to beta and (2) starting with a combined alpha-and-beta position, separating them, and then adding the resultant alpha to a different beta.

- This report augments the understanding of portable alpha today with a comparative data review of practices at select large endowments that employ portable alpha—discussing their use of portfolio-level leverage, method of implementation (in-house or external), sources of alpha, and beta exposures.

- Potential benefits of portable alpha include more opportunity for alpha, increased flexibility in managing exposures precisely to policy targets, and potential for lower fees given use of derivatives. Potential drawbacks of portable alpha include the critical need to manage liquidity, the use of leverage, and the elusive nature of alpha—is this alpha any better?

- Practitioners note that a good, liquid source of alpha is key, coupled with prompt access to a liquidity reserve and appropriate governance practices. One of the challenges facing institutions that employ portable alpha is a lack of managers that reliably generate alpha, are liquid, and are uncorrelated to other alpha sources already in the portable alpha program.

- Portable alpha is not a simple solution to the problem of low equity and bond returns. These programs are complex and have been used with limited success by the largest endowments. For most investors, diversification, comprehensive manager due diligence, and risk control remain the keys to success.

Capital markets move in cycles. In another research report, we made the following observations about the market environment, and how some investors were looking to portable alpha as a potential solution to expected muted returns:

Mike Walden, “Portable Alpha: A Closer Inspection,” Cambridge Associates Research Report, 2005. Our prediction on mid-single-digit expected returns was borne out: for the ten years from 2005 to 2014, the assets of the median endowment grew at 6.3% per annum (nominal), during which time US inflation averaged 2.1%.

Investors have slowly come to grips with the tough math facing prospective US equity and bond returns. Higher-than-average equity valuations, lower-than-average dividend yields, and 40-year lows in interest rates, suggest that investors will be lucky to earn returns in the mid-single digits over the next decade. This presents a daunting challenge for institutions that seek to grow assets in real terms and spend 5% per annum. As a result, we continue to recommend carefully diversifying portfolios by function and including various alternative investments to create the mix of assets most likely to pay the bills, most often. Some members of the money management industry, on the other hand, have been designing financial products to “solve the investor’s problem.” Portable alpha is one such approach, focusing on funding alpha sources wherever they exist and separating alpha from beta through the use of index derivatives. Of course, the trick has never been in separating the two sources of return, nor in mobilizing them, but in identifying consistent alpha, holding onto it, and hoping it does not morph into beta when diversification is needed most.

Tellingly, the quoted report was not released recently, but rather ten years ago. Despite the investment roller coaster of the ensuing period, equity valuations and dividend yields are as comparably high and low, respectively, as they were in 2005, while interest rates are now considerably lower than they were then. Because quite similar things could be said about the current environment, we thought it fitting to revisit the topic of portable alpha.

In this report, we augment the understanding of portable alpha today with a comparative data review of practices at select large endowments that employ portable alpha, although we begin with the underlying theory to lay a foundation. We still draw the same conclusions we did earlier: namely, that portable alpha is not a simple solution to the problem of low equity and bond returns, that the strategy includes many risks, not the least of which is identifying the sources of alpha, as well as ensuring the liquidity of the alpha sources, monitoring for any beta embedded in the alpha sources, and managing the portfolio leverage.

Portable Alpha in Theory

Portable alpha is a strategy that allows investors to combine the alpha from one investment with the beta from another. This is done by using derivatives, such as futures, forwards, or swaps. Traditionally, a cash-funded (or “physical”) investment has come with some sort of beta exposure and, if it is an actively managed investment, with some alpha as well, which is the return out- or underperformance not attributable to beta. Because the alpha and beta have been bundled together, investors were faced with the challenge that they may find a manager’s alpha stream to be attractive, but not the beta. For example, an investor might desire a 10% allocation to a manager and its alpha, but the policy portfolio has a target allocation of only 5% to the asset class that the manager is in, and the investor doesn’t want the extra 5% of beta exposure. What is to be done?

The use of derivatives permits investors to gain “synthetic” exposure to an investment, which allows the alpha and beta return streams to be separated and recombined. The synthetic exposure is typically to a passive investment such as an index. This constitutes the beta, and is termed the “beta overlay.” But unlike cash investments, which are fully funded, with derivatives only a small fraction of the exposure is required to be funded from cash. This collateral, also known as margin, is posted to a broker and used to secure the derivatives position.

The difference between the value of the synthetic exposure and the value of the collateral is termed “unencumbered cash.” If the investor chooses to hold this as cash, the derivatives position is termed “fully collateralized.” This is the least risky implementation of derivatives, since such a position uses no leverage. That is, its economic exposure is the same as the value of its assets, and on a $100 investment the most that could be lost is $100. At the same time, a fully collateralized position gives the investor only passive exposure to an asset class: no alpha, just beta.

If instead the investor chooses to deploy some or all of the unencumbered cash in an asset other than cash, that investment has the potential to earn a return above (or below) cash. This combination of derivatives, some cash collateral, and some non-cash investment does use leverage, as its economic exposures now exceed the value of its assets. The position funded from unencumbered cash constitutes the alpha. Strictly speaking, this position should have little to no correlation to the beta overlay for the combination to be considered portable alpha, otherwise the investor is just levering up the beta exposure.

Conceptual Examples

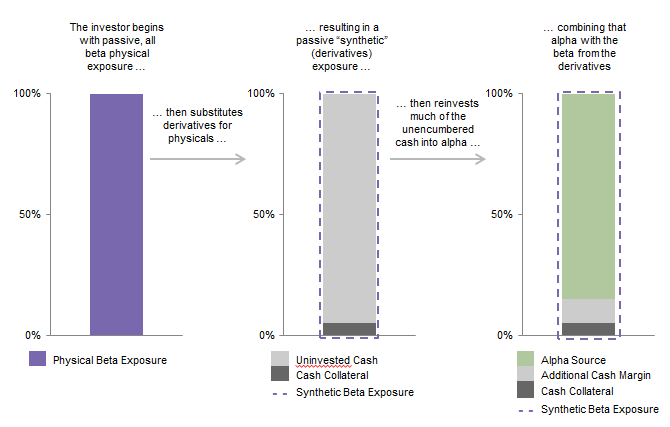

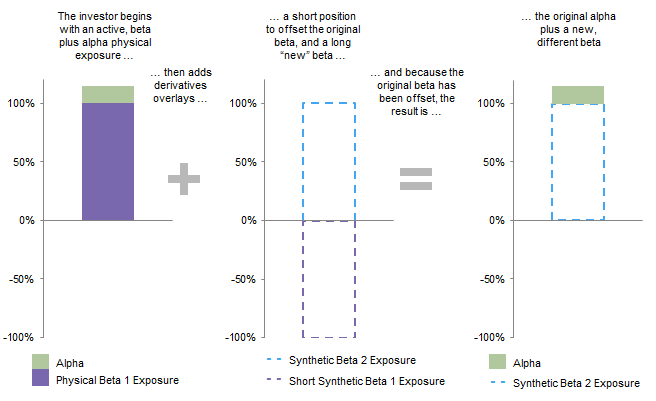

Investors have two main ways to craft a portable alpha position. The first adds pure alpha to beta (Figure 1). This approach was broadly described above, but to illustrate it more concretely, consider an investor wishing to beat the S&P 500’s return in its US equity allocation. As US equities are considered a relatively efficient asset class, the investor might question whether active managers could be found in this space that deliver consistent positive alpha, net of fees. If instead the investor finds a manager in an unrelated asset class, such as absolute return, it could start with $100 in cash, set aside some $10 as collateral and buy an S&P 500 futures contract, and invest most of the remaining $90 in the absolute return manager (a small amount would be retained as additional collateral). The combined position would be exposed to the beta from the S&P 500 futures and to the return stream from the absolute return manager. Provided the latter truly was uncorrelated to equities, it would constitute alpha—and if it delivered consistent positive net returns, then this portable alpha position would outperform the S&P 500.

The second variant starts with a combined alpha-and-beta position, separates the alpha from the beta, and then adds the resultant alpha to a different beta (Figure 2). Again consider an investor trying to beat the S&P 500, but in this example, imagine that the investor has identified an excellent US small-cap equity manager that delivers alpha year in and year out. From a risk management standpoint the investor would be comfortable holding a large position with the manager, but does not want that much beta exposure to small caps. Here the investor could start with a $100 position with the small-cap manager, overlay a short futures contract in the Russell 2000® Index to offset some or all of the manager’s small-cap beta, and also overlay an equally sized long S&P futures contract to add back in an equivalent exposure to large-cap equities. This combination brings together the beta from the S&P 500 futures and only the alpha from the small-cap manager, and again would outperform the S&P 500 if the small-cap manager delivered positive net returns relative to the Russell 2000®.

The two approaches arrive at the same result, but in practice we have seen more implementations that follow the first method. This is because the second approach requires considerably more gross leverage than the first, and because it is challenging to know exactly how much beta is present in the combined alpha-and-beta position and thus how large to size the short beta position to offset the manager beta precisely.

Potential Benefits

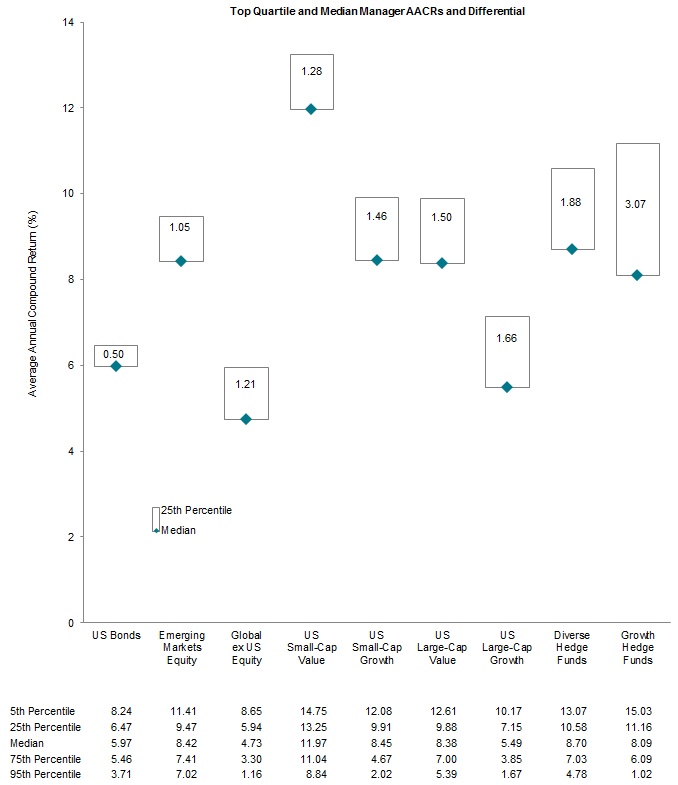

More Opportunity for Alpha. Manager alpha is elusive and ephemeral. That said, alpha is harder to find in some asset classes than others—the more efficient the asset class, the less dispersed manager returns tend to be, and thus the more challenging it is to find alpha (Figure 3).

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: The label in each bar shows the difference in average annual compound return between the top quartile (i.e., 25th percentile) and the median (i.e., 50th percentile) managers for each asset class. Data are based on managers with a minimum of $50 million in assets.

Policy portfolios typically allocate some portion of capital to such asset classes; using physical investments, there are two choices: give up on alpha and go passive, or go active and hope that the higher fees do not completely erode any thin alpha that the manager might deliver. Portable alpha enables the third choice of bringing in alpha from someplace else where it might be more abundant. Indeed, implementers of portable alpha have usually looked to employ it for their fixed income and their large-cap domestic and developed international equity allocations—the more efficient asset classes where alpha is thought to be harder to find.

Increased Flexibility. The use of derivatives overlays for the beta also enables greater flexibility and precision in keeping allocations on target. If a portable alpha program had equity and fixed income futures atop the alpha sources, and market moves meant that the program’s exposures deviated from their policy targets, rebalancing to target is just a matter of dialing up one futures contract and dialing down the other, and can be executed immediately. This is a clear improvement over waiting for manager liquidity windows and suffering frictional cash drag if the proceeds from manager X cannot be immediately redeployed in manager Y. The same flexibility would also permit faster implementations of tactical tilts.

Fee Breaks. The beta portion of portable alpha—the derivatives overlays—comes with minimal fees. If alpha managers are identified whose fees are lower than active managers in the asset classes where portable alpha is intended to substitute, then the portfolio will save on manager fees overall.

Potential Drawbacks

Is This Alpha any Better? As noted above, manager alpha is elusive and ephemeral. While portable alpha proponents may point to asset classes where they believe the alpha opportunities are more favorable, finding managers anywhere that deliver positive alpha, net of fees, consistently over time remains difficult. If managers included in a portable alpha program are selected poorly, although they indeed will contribute alpha, the alpha may end up being negative.

Liquidity Management Is Critical but Challenging. The primary risk of a derivatives overlay is that a sharp market downturn may occur, causing the broker (who holds the collateral) to demand additional margin to ensure a sufficient amount of collateral is on hand to support the derivatives positions, as mandated by regulatory requirements. If such additional margin is “called” but not provided promptly, the broker is empowered to “unwind” (sell) the derivatives positions, leaving investors without market exposure against their will. If markets then revert, derivatives investors would suffer the downside but be without exposure and miss the upside. (In contrast, investors with exposure through physical positions would suffer the same downside but not be forced to unwind their positions, and would benefit from the upside.)

To prevent this chain of events, the derivatives investor must have access to liquidity to meet reasonable worst-case margin calls. For example, the size of the worst ever one-day loss in US equity markets, “Black Monday” in 1987, was 23%. If the portable alpha program’s alpha managers were sufficiently liquid that about a quarter of the positions could be converted to cash within a day, this would probably provide an adequate margin of safety—although contingency plans to backstop these positions with others that could be liquidated in three days, or a week, or a month would also be desirable in case markets continued to fall. Other approaches could include holding a portion of the unencumbered cash as cash rather than re-investing it elsewhere, having access to cash outside the portable alpha program (but still inside the total investment pool), and having a line of credit that could be drawn upon. Not having some combination of these safeguards in place would constitute a reckless implementation of portable alpha.

Note that if portable alpha is not executed in-house, but instead is accessed by investing in a “one-stop shop” manager that handles all the details of combining an alpha stream with a beta overlay (as we describe further in the next section), then liquidity management of portable alpha is also completely that manager’s responsibility.

Portable Alpha Constitutes Leverage, for Good or Bad. Two concerns stand out here. First, the alpha source should have little to no exposure to the derivatives beta overlay. To the extent that some unintended beta exposure creeps into the alpha manager’s returns, the strategy becomes a levered play on beta, which magnifies the return potential and volatility, for both upside and downside. Second, even if the alpha and the beta are completely separate and uncorrelated, uncorrelated is not the same as negatively correlated. It’s entirely possible that, by happenstance, the alpha position and beta overlay could decline at the same time. This too would be a worse outcome than holding just the beta—the downside is magnified by leverage. For a portable alpha program executed in-house, this could result in losing more money than was originally invested. Outsourcing instead to a manager creates a “wrapper” around the position that ensures that investors cannot lose more money than they gave to the manager, but the leverage risk remains inside the manager and must be dealt with.

Portable Alpha in Practice

In response to a client request to better understand the use of portable alpha and portfolio-level leverage,[1]Most institutions are exposed to leverage of some sort, potentially at multiple levels. Most endowment portfolios have leverage embedded within manager vehicles, especially if alternative assets are … Continue reading including common themes, best practices, and potential pitfalls, we interviewed several large endowments, either via telephone or in person. Our sample comprised six major research universities and five leading foundations, all located in the United States, selected based on our knowledge of our clients’ practices. Note that this is not an exhaustive sample of C|A’s clients using portable alpha—a few of those that were approached declined to take part. Those institutions that did take part agreed to let us share general, high-level findings of the study provided that they were anonymized.

Of the 11 client institutions in our sample, nine currently use portable alpha, one is a recent but former user of portable alpha, and one does not use portable alpha but does employ portfolio-level leverage. All endowments are $2.5 billion or larger in size; specifically, four are in the $2.5 billion to $5 billion range, four are $5 billion to $10 billion, and three are greater than $10 billion.

We should highlight that the use of portable alpha is relatively uncommon even among well-resourced and sophisticated endowments. Even though a few of our clients known to practice portable alpha did not participate in this study, the 11 in our sample constitute a small minority of the full population of over 50 CA endowment clients with $2.5 billion or more in assets. One explanation for this relatively low usage is that the practice of portable alpha was more widely adopted during the decade of the 2000s, but a number of users discontinued portable alpha in response to poor results during and after the financial crisis—too much at the wrong time led to very bad results in a couple cases. Of our sample, one institution incepted portable alpha prior to 1990, two during the 1990s (of which one stopped the practice in the 2000s), seven in the 2000s (including the one client that does portfolio-level leverage but not portable alpha), and one in the 2010s. Thus our sample is skewed toward the portable alpha “survivors” of the financial crisis.

Degree of Leverage

Determining the degree of leverage employed by practitioners turns out to be complicated, as institutions use competing definitions. To create a standard comparison we defined leverage as the ratio of net notional exposure to capital assets. With this definition, a portfolio employing no leverage would have a metric level of 100% (or, put another way, 0% excess leverage). Practitioners in our sample ranged from approximately 105% to 116% leverage.

Additionally, we would highlight a notable practice: one institution recognized that a useful metric of leverage may depend upon the underlying volatility of the levered asset—e.g., levered equities contribute more to portfolio volatility (and thus “matter more” to total leverage) than levered bonds. To incorporate this, the institution tracks its leverage metric standardized to its portfolio’s target volatility, where higher volatility assets contribute a higher weighted leverage, and so forth.

In terms of other leverage metrics: although employing leverage implicitly requires holding “negative cash,” only two institutions in our sample report that their asset allocation targets (i.e., their “policy portfolios”) reflect a negative cash line item or a leverage target. Furthermore, leverage within the endowment is not reliant upon direct borrowing: most institutions deliberately choose not to have access to a line of credit within their endowment (even though the broader institutions often have access at the operating level). Only four sample institutions have lines of credit, as an emergency backstop for liquidity during stress periods, but none of those four reports having yet used the line.

Spectrum of Implementation

In theory, a portable alpha program could choose to source its alpha in-house or externally, and likewise could overlay beta in-house or externally. Furthermore, if both are run externally, they could be outsourced separately or together; the latter would be a portable alpha one-stop shop manager (Figure 4).

As a general rule, portable alpha practitioners in our sample follow a similar process of identifying a pool of dedicated external alpha source managers and overlaying beta exposures via derivatives that are run in-house, thus combining the “ported” alpha and the passive beta, and categorizing that return under the asset class corresponding to the beta exposure. However, there are a number of variations and nuances around this broad approach.

On the alpha side, some institutions run their own internal alpha-generating strategies in addition to hiring external portable alpha managers, generally through two methods. The first method of doing so generates portable alpha purely by overweighting certain active managers (versus their “policy target” weights) and then shorting the overweight portion of those managers’ beta. For example, an institution may target a manager to be 5% of the portfolio, but hold 6%, and short the excess 1% of beta (separating out the alpha). The institution doing so describes its portable alpha as not the primary goal but rather a byproduct of using derivatives to synthetically rebalance its portfolio to policy (beta) targets.

The second approach is to generate most portable alpha internally (i.e., run the same sort of strategies that external portable alpha managers would use, but do so in-house), but even in this case the one practitioner in our sample that follows this approach does not do so exclusively, hiring a small number of external managers as well. An in-house practice requires substantial scale and resources, and thus is the exception—while a few other institutions in our sample run small internal alpha-generating strategies, they predominantly rely on external sources.

On the beta side, two practitioners in our sample employ a third-party service provider to implement the derivatives overlay, rather than handling the trading in-house. While these were on the smaller side in terms of assets within our sample, they were not the smallest institutions; that is, at this scale level of resources and staff, it is a reasonable choice to decide either to hire your own traders or to hire someone else to do the trading for you.

Finally, regarding the combination of alpha plus beta, one practitioner that we interviewed completely outsources its portable alpha operations to a set of external managers. In this case, the institution relies on three managers to provide products that package the portable alpha plus a beta overlay—in the words of this institution, “complete solutions.”

Alpha Source Managers

The prevailing practice employed by our sample’s institutions to generate the alpha to be “ported” is to employ a set of external managers. In most cases, these managers are dedicated absolute-return type hedge funds, identified because of three key criteria.

First, portable alpha managers must have good liquidity. As noted above, investments in these managers are made using funds that would otherwise be used to fully collateralize the derivatives in the beta overlay. In a worst-case scenario, after other liquidity reserves had been exhausted, these managers might need to be tapped for cash to meet margin calls.

Second, managers chosen need records of successful alpha generation. This is perhaps an obvious criterion given their purpose, but interesting in that liquidity was prioritized higher—as institutions recognize that unexpected illiquidity is much more dangerous than unexpected alpha underperformance.

Third, managers’ records also have to show little to no beta to risk markets. It is a bit surprising that this was only the third-highest requirement, given our understanding that many of the practitioners that were burnt by portable alpha during the crisis—and ended the practice—did so because they were surprised by the amount of embedded beta they found in their managers (at least during stress periods). The “survivors” in our sample essentially take it as a given that alpha managers needed to have minimal beta, in both normal and stressed markets[2]Some strategies that exhibit little-to-no correlation to equities in normal markets can exhibit more beta during stressed periods when risk aversion spikes, liquidity dries up, and the correlations … Continue reading—therefore all of them explicitly avoid using long/short hedge funds in their alpha pool. However, two practitioners did say they are willing to accept some level of more-than-zero beta in their alpha managers, which they would offset by adjusting their beta overlay to be less than one.

Two additional desirable characteristics that our sample’s institutions noted are, first, a theoretical basis for the expectation that their selected managers would continue to have minimal beta to risk markets, and second, a record of minimal correlation among their alpha source managers. Specific strategies employed by the alpha managers selected by these institutions include:

- Catastrophe bonds,

- Legal claims,

- Global macro,

- Fixed income arbitrage,

- Fixed income relative value,

- Commodity pairs trades,

- Ultrashort duration fixed income,

- Direct lending, and

- Harvesting the option volatility risk premium.

Beta Exposure Overlays

Most practitioners began the beta overlay portion of their portable alpha programs by using futures. Some of the more highly resourced institutions then shifted into using swaps (e.g., total return swaps) and options. Among our sample, eight institutions use futures, six use swaps, and four use options.

The most common exposures overlaid via these derivatives are fixed income (nine institutions) and equity (eight), followed by currency (six), then commodities and volatility (four each). Several of the practitioners use their beta overlays to synthetically adjust their risk exposures to be at target levels.

One institution took a creative and unusual approach in which it combined portable alpha with hedge fund replication. That is, using factor analysis the institution determined the beta exposures of its hedge fund program, and then overlaid those beta exposures atop alpha sources. The goal was to potentially deliver hedge fund performance with lower fees and better liquidity.

“One-Stop Shops”: Portable Alpha Managers

Running a portable alpha program clearly involves a lot of moving parts. Most institutions, and particularly those with smaller scale and resources, will likely not have core competencies in generating an alpha source (as opposed to identifying alpha managers) or in managing a derivatives beta overlay. Furthermore, the notion of portfolio-level leverage—as opposed to leverage embedded in investments with external managers—may give pause, either to an investment office or to an oversight body. Such investors seeking to employ portable alpha do have the option of investing with external managers whose products bundle a portable alpha source with a beta overlay. Use of such “one-stop shops” is more commonplace than the portable alpha approaches employed by the large institutions we interviewed—some 12% of our clients of any size whose performance we track have hired these portable alpha managers—but is still rare.

- These one-stop shops with “turnkey” solutions offer several advantages:

- Investments are made as with any other fund: you write a check to the manager, you get a return, at some point you ask the manager to write a check back to you,

- The manager takes care of generating the alpha, presumably in a market segment where it has a competitive advantage,

- The manager takes care of the beta overlay, and

- The investor cannot lose more money than was invested; that is, while the product contains leverage, it is embedded in the product “wrapper,” which means that the manager must deal with leverage and liquidity management, but this dynamic risk control is invisible to the investor.

- On the other hand, these products also have certain considerations:

- A fee is paid to the manager—how does that compare with the cost of doing the alpha, the beta, or both in-house?,

- The product is less flexible than an in-house solution: if the alpha source falters, the only option is to redeem, and if the beta overlay needs to be adjusted, this is doable but not as swiftly as if the investor was managing the beta overlay directly, and

- The product is less liquid than an in-house solution.

We are aware of roughly a half-dozen institutional-quality one-stop-shop portable alpha managers with about a dozen distinct products, which in turn come in multiple “flavors” depending on the beta overlay chosen. Of these, while all but one have positive five-year annualized compound returns, on a year-by-year basis the alpha has been anything but consistent, and only one has a record of adding value every year. For this service, this manager charges hedge fund–like fees of 2% and 20%, with an account minimum of $30 million—and is closed. While outsourcing has its attractions, it is not a panacea.

Practitioners’ Keys to Success (or, Ways to Avoid Pitfalls)

A number of themes came up repeatedly during our interviews with clients of how to be successful or avoid pitfalls when employing a portable alpha program.

First, and above all, good, liquid alpha sources are needed. In particular, investors need to have reasonable assurance that there is minimal-to-no embedded beta in these managers, either in regular or in stressed markets (e.g., 2008). A few institutions bluntly noted that they were hurt by discovering too late that, during the 2008 stress period, their alpha source managers had considerable amounts of beta and/or needed to put up gates, negatively impacting the liquidity of those alpha sources. Others noted that the returns of their alpha sources, like those of many managers, have been “streaky,” with positive and negative periods. Diversifying among a pool of unrelated alpha sources can help to mitigate this, but as we have stressed, manager alpha is elusive and ephemeral.

Next most importantly, because liquidity management is critical but challenging, one needs to maintain a good, promptly accessible liquidity reserve, even apart from the liquid alpha sources. While holding these additional highly liquid reserves is dilutive to the portable alpha returns, investors must accept this dilution as a “cost of doing business.” Most practitioners have comparable portfolio levels of both illiquidity (e.g., 40%–50% of total assets in private investments) and semi-liquidity (e.g., 15%–30% in hedge funds with lockups greater than one year). Even so, practitioners appear comfortable with that much illiquidity, provided that they have run stress tests to properly size their level of highly liquid assets. Such stress tests include worst-case scenarios such as: margin calls on the beta overlay from a 2+ standard deviation downside event, and high capital calls on unfunded privates, and accelerated distributions to the institution, and increased operating expenses. One institution, notably, maintains sufficient one-day liquidity to handle a 1 standard deviation stress, sufficient three-day for a 2 standard deviation stress, and so forth. Also, as mentioned, a minority of the sample maintain untapped lines of credit as a backup during a crisis.

The third most important element of success involved governance: the investment committee or other oversight body needs to understand the portable alpha program, buy into it, and authorize it. Because the practice is unfamiliar to most and is conceptually complex, several meetings are often required prior to its approval. A further complication is that portable alpha requires leverage and derivatives, which are considered to be “two of the three dirty words of finance,”[3]The third is “shorting,” which some implementations of portable alpha may use as well. and which therefore are often explicitly barred from the portfolio in investment policy guidelines—institutional comfort in using derivatives was surely not helped when Warren Buffett called them “financial weapons of mass destruction.” Guideline revisions that permit their use would have to be carefully crafted for institutions with existing restrictions, since as we have noted, portable alpha constitutes leverage, for good or bad.

Two governance practices that we found notable were, first, tiers of authority—the investment office has full discretion within a certain leverage range, then discretion with the IC chair’s approval in a higher range, and finally full IC approval above that range—and second, expert subcommittees—rather than bringing portable alpha issues to the whole committee, a smaller subcommittee of IC members with derivatives expertise is tapped to provide oversight.

Expansion of Programs

The general sentiment among the institutions in our sample is that their portable alpha programs have served them well—since they had survived the financial crisis and were continuing to employ them, this should not be a surprise. Furthermore they broadly agree that they would consider expanding their programs if they could. However, they are constrained not by their willingness but by their ability—they perceive a lack of availability of additional alpha source managers. Specifically, they are challenged by the prospect of adding managers that are:

- Reliable in their alpha generation, and

- Liquid, and

- Uncorrelated to the other alpha source managers already in their program.

Conclusion

We do not intend to rule on whether portable alpha is “good” or “bad.” A better question might be “how much of the portfolio should be allocated to it?” The strategy has both potential benefits and drawbacks, as summarized at right. It can be a useful addition to investors’ toolkits, but as evidenced by the relatively limited uptake—with only 12% of our clientele using the easiest-to-implement one-stop shops, and under a third of our largest and most well-resourced clients attempting to do it in-house—it’s clearly not for everyone. Investors need to ask themselves whether they believe in consistent alpha and whether they have access to it. If yes to both, how do they want to implement portable alpha—via one of the few institutional-quality outsourced options, or in-house? And if the latter, do they have the capabilities to manage the liquidity and the leverage of a portable alpha program, both in benign and turbulent markets? The larger the program, the more leverage it uses, and the more concerns we would have, particularly when markets get choppy.

In short, portable alpha is not a simple solution to the problem of low equity and bond returns. These programs are complex and have been used with limited success by the largest endowments. For most investors, diversification, comprehensive manager due diligence, and risk control remain the keys to success.

Potential Benefits

- More opportunity for alpha—not constrained by limits of asset allocation

- Increased flexibility—in managing exposures precisely to policy targets

- May achieve lower fees

Potential Drawbacks

- Are the additional alpha opportunities any more additive to value, or any more consistent?

- Must manage liquidity—in case of downturn that forces margin calls to support beta overlay

- Portable alpha does require leverage

Footnotes