Last February, the former director-general of the World Trade Organization testified before Parliament’s Brexit committee and opined that the United Kingdom’s divorce from the European Union will be “as difficult as removing an egg from an omelet.” This complex and divisive issue has weighed on the UK economy and impacted sterling asset performance since the 23 June 2016, referendum on EU membership. The rise in risk premiums since the landmark plebiscite has left valuations for the British pound and domestic equities below their historical averages, while Brexit-related economic uncertainty has kept a lid on gilt yields. Crucially, having some exposure to unhedged foreign currency–denominated assets in recent years has helped to buffer some UK domestic risks as the pound depreciated. Today, UK investors face two critical, and somewhat interrelated, questions: (1) should they tilt further toward UK equities relative to policy, and (2) does the policy target or minimum for aggregate sterling-denominated asset exposure need revisiting?

Regarding the first question, we don’t believe sterling-based investors should increase exposure to UK equities relative to policy (beyond the modest overweight associated with our broader allocation tilt to global ex US stocks vis-à-vis US equivalents). Valuations for UK equities are certainly undemanding, and dividend yields are among the highest on offer globally. However, in addition to Brexit risks, today’s valuations for the UK equity market as a whole also reflect a relatively unattractive industry mix and an above-average exposure to idiosyncratic company risk.[1]This is less of an issue for actively managed UK equity strategies because local managers tend to overweight mid- and small-cap stocks. However, these portfolios tend to exhibit high tracking error, … Continue reading In terms of revisiting the portfolio’s target range for sterling-denominated asset exposure, we do not believe it is necessary to adjust the overall level of sterling exposure—either tactically or strategically—in anticipation of any specific Brexit outcome. The pound has already sustained a substantial depreciation, and its valuation is currently below average, suggesting a fair amount of Brexit impact is already priced into the currency. Indeed, political economists now assign higher probabilities to outcomes that would be positive for sterling than to negative scenarios. However, given the difficult-to-predict political dynamics, sterling still faces tail risks not just to the upside, but also to the downside.

For a further discussion of the opportunities and risks associated with Brexit for the UK property market, please see Kevin Rosenbaum and Daniel Day, “UK Property: Finding Opportunity Amid Heightened Political Risk,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, October 2016.

The real elephant in the room for some UK institutional investors is their exposure—in some cases, sizeable—to UK property, either directly or through listed trusts. Certain categories of UK property are highly exposed to any weakening in the domestic economy. In addition, cap rates remain near historical lows, though spreads relative to domestic investment-grade fixed income remain well above average. Furthermore, allocations to property reduce portfolio liquidity and limit tactical flexibility. However, these holdings are strategic in nature for some investors, and a detailed discussion of UK property is beyond the scope of this report.

Brexit Is a Process, Not an Event

After weeks of Parliamentary debate and procedural maneuverings, UK and EU27 negotiators’ tentative withdrawal agreement from November remains in limbo.[2]The two sides have been unable to forge a solution on the so-called “Irish backstop” that is acceptable to a majority in the UK Parliament and to all EU27 member governments. The Irish backstop … Continue reading The Article 50 negotiations, which began nearly two years ago, are now building to a crescendo as “Brexit day” (29 March 2019) rapidly approaches.[3]29 March 2019, marks the end of the two-year period by which the United Kingdom and the EU must negotiate, ratify, and codify into domestic law a withdrawal agreement as stipulated by Article 50 of … Continue reading Despite the build up to this deadline and the possibility of a near-term resolution regarding the terms of the UK withdrawal, the ultimate Brexit outcome may not be known for some time, given the herculean task of unwinding years of economic and political convergence and developing a new relationship. To quote a member of Parliament, who recently likened Brexit to the Welsh devolution, “Brexit is a process, not an event.” Though it’s possible the United Kingdom and EU27 will not be able to agree to terms of the withdrawal (termed a “no-deal” Brexit), the odds of this are fairly low.[4]Under a “no-deal” Brexit scenario the United Kingdom would leave the EU with no withdrawal agreement in place. Trade between the two would revert to WTO rules either immediately (i.e., “a crash … Continue reading But even assuming the United Kingdom begins the process of leaving the EU with a withdrawal agreement in place, it could still be several more years before the final Brexit end state—that is, the future political and economic relationship—becomes clear. This would be particularly true in the event that the United Kingdom ultimately decides to make a mostly clean break from the EU and attempts to negotiate a new bilateral free trade agreement, as the May administration has set out to accomplish (Figure 1). Investors should therefore maintain a long-term perspective and ignore the near-term Brexit noise, though that is easier said than done.

Source: Barclays.

UK Economy Has Lagged Since “Leave,” but Context is Important

UK economic growth has gradually decelerated over the past five years, a trend that has continued since the country’s momentous vote to leave the EU trading bloc more than two and a half years ago. Growth peaked at 2.9% in 2014 but, in 2018, the UK economy expanded only by 1.4% year-over-year, its slowest pace since the global financial crisis. The Bank of England has estimated that Brexit uncertainty has already cost the UK economy approximately 2.0% of GDP. Since the Brexit referendum, businesses have put investment plans on ice, the conservative government has continued to shrink the fiscal deficit, and the UK economy has become more reliant on increasingly indebted and decreasingly confident British consumers for growth (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the number of EU27 nationals in the labor force has declined, and the trade deficit has not improved despite the more competitive pound.

FIGURE 2 INFLATION-ADJUSTED GROWTH IN UK FIXED BUSINESS INVESTMENT, PRIVATE CONSUMPTION, AND GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURES

First Quarter 2011 – Fourth Quarter 2018 • 30 June 2016 = 100

Source: UK Office for National Statistics.

Notes: Inflation-adjusted fixed business investment, private consumption, and government expenditures data have been rebased to 100 as at 30 June 2016, just after the Brexit referendum. This chart compares the relative growth trends in these three specific components of GDP, and does not reflect the relative contribution to overall GDP growth by each category. In addition, several other GDP components are intentionally excluded: construction, net exports (imports), and inventory changes. Inflation data are represented by the seasonally adjusted implied GDP deflator at market prices.

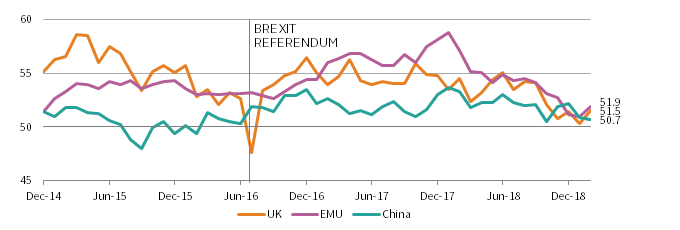

The slowdown is concerning, but the domestic business cycle and policy environment, as well as the external macroeconomic backdrop, all provide important context. Given the British economy’s reliance on trade, it’s difficult to disentangle how much of the recent deceleration has been driven by domestic versus external factors. Looking at recent trends in the composite purchasing manager indexes (PMIs), both the decline in UK business sentiment and the current level are quite similar to those for the Eurozone and China (Figure 3). In addition, the United Kingdom’s latest reading indicates expectations for an ongoing, albeit weak, expansion. This is in contrast with the data immediately following the Brexit referendum, which had reflected fears of a sharp near-term contraction. These suggest that the United Kingdom’s economic weakness stems from weakening global activity, as well as ongoing Brexit uncertainty. One potential corollary is that UK policymakers may find the impact of any monetary or fiscal stimulus efforts to be limited in the face of any “no-deal” scenario.

FIGURE 3 COMPOSITE PURCHASING MANAGER INDEX (PMI) BY REGION

31 December 2014 – 28 February 2019 • Index Level

Sources: Markit Economics and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Note: A PMI reading above/below 50 indicates an expanding/contracting economy.

Sterling is the Brexit Bellwether

For a further discussion of historical bear market cycles for sterling, please see Aaron Costello and Han Xu, “Has the GBP Bottomed? Not Likely,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, July 2016.

The United Kingdom is a large open economy and the EU is, by far, its largest trading partner. Therefore, trade dynamics between the two are critically important for the United Kingdom, with the exchange rate the primary mechanism by which the UK economy will adjust to the ultimate Brexit end state. Since the referendum, the trade-weighted pound appears to have moved to a structurally lower trading range in anticipation of greater trade friction between the United Kingdom and the EU, as well as the prospect of having to negotiate new bilateral trade agreements with dozens of non-European trading partners. Despite a 4% year-to-date rally, sterling remains 7% below the level at which it traded in the months leading up to the Brexit vote. During January 2017, at its weakest point following the referendum, the pound had fallen 30% (in USD terms) from its July 2014 peak; this drawdown was exactly in line with the average maximum decline observed during eight past sterling bear markets over the past five decades, including in the immediate aftermath of “Black Wednesday.”[5]Black Wednesday refers to 16 September 1992, when a collapse in the pound sterling forced Britain to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM).

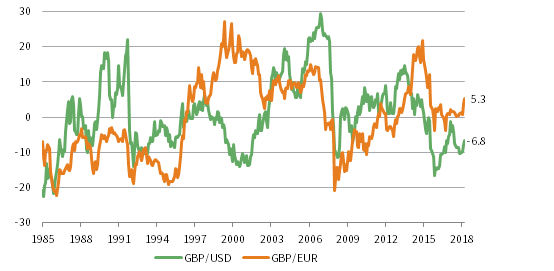

Arguably, the currency has now priced in much of the potential impact of the “hard, but orderly and prolonged” Brexit deal on the table in Parliament. Currently, the pound’s valuation remains somewhat below its historical average on a trade-weighted basis, but this is primarily driven by its exchange rate with the pricey US dollar. In contrast, the pound’s real exchange rate with the euro is now above its historical median (Figure 4). An unlikely (but not unthinkable) scenario in which the United Kingdom “crashes out” of the EU could deliver a sizeable economic shock that would likely further batter the pound. On the flip side, it’s difficult to see sterling returning to pre-referendum levels in the near future unless Brexit is ultimately cancelled, which would probably require a new general election and a second plebiscite, a scenario whose odds also appear low at this time. Setting aside these low-probability tail risks, the more likely outcome will be for the pound to continue to trade within its post-referendum trading range for the foreseeable future, given expectations for prolonged uncertainty regarding the ultimate Brexit end state.

FIGURE 4 GBP VALUATION: PERCENT DEVIATION OF REAL EXCHANGE RATE FROM HISTORICAL MEDIAN

31 December 1985 – 28 February 2019 • Percent (%)

Sources: MSCI Inc., Thomson Reuters Datastream, and WM/Reuters. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Note: UK and US inflation data are as at 31 January 2019.

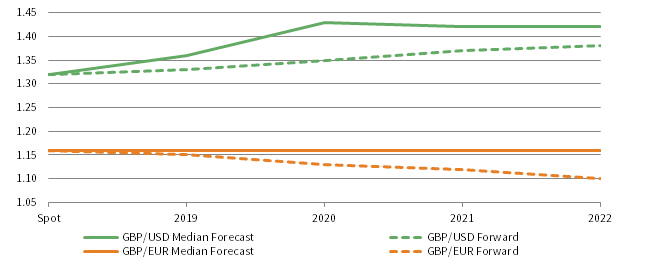

Valuations are important drivers of currency exchange rates over longer horizons, yet political developments that risk shifting economic and trade policies can be more impactful over the near term. Therefore, Brexit developments have been an important driver for sterling over the past three years, and this will continue until the United Kingdom and EU iron out the details of their future political and economic relationship. Today, both the consensus view of professional forecasters and the market for currency forwards predict that the pound will appreciate versus the US dollar back to the upper end of its post-Brexit trading range over the next four years, whereas the GBP/EUR exchange rate expectations are for modest weakening (Figure 5). Beyond that time horizon, relative macroeconomic fundamentals and valuations between sterling and trading partner currencies will have more influence.

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

UK Equities: Fundamentals and Valuations a Mixed Bag

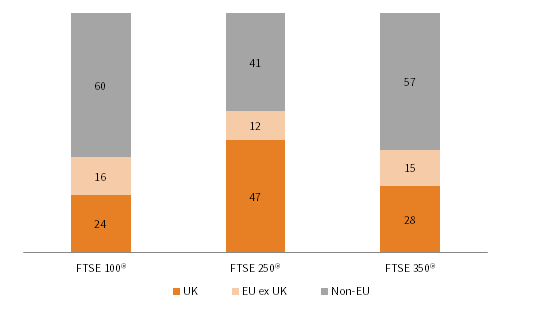

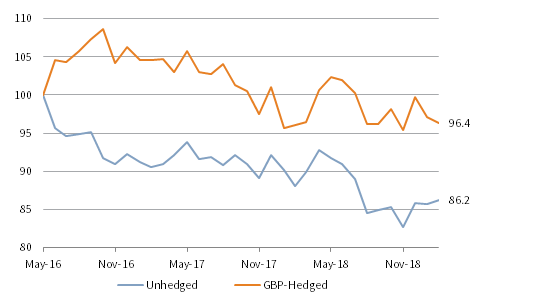

The globally oriented revenue stream of the UK equity market is somewhat insulated from the Brexit-related domestic slowdown and the prospect of increased trade frictions with the EU. The UK equity market is the least domestically oriented of any major stock index. More than 75% of UK large-cap sales are sourced outside the United Kingdom, and even the more domestically oriented mid-cap universe derives only about half of its revenues from home (Figure 6). As a result, the performance of UK stocks relative to broader developed markets has been negatively correlated with sterling historically, though that has been less true recently as the pound became the bellwether for Brexit risks. For unhedged sterling-based investors, relative results of UK stocks versus broad developed markets equities have been dismal, since just before the Brexit referendum, given the large depreciation in UK sterling immediately following the outcome. However, for fully hedged sterling investors, UK equities have lagged broader developed markets stocks by far less (Figure 7).

Sources: FactSet Research Systems and FTSE International Limited.

FIGURE 7 RELATIVE CUMULATIVE WEALTH: UK VS DM EQUITIES

31 May 2016 – 28 February 2019 • 31 May 2016 = 100

Sources: FTSE International Limited and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Total return data are monthly and gross of dividend taxes. UK and DM equities return data are represented by the FTSE® 350 Index and FTSE® All World Developed Markets Index, respectively.

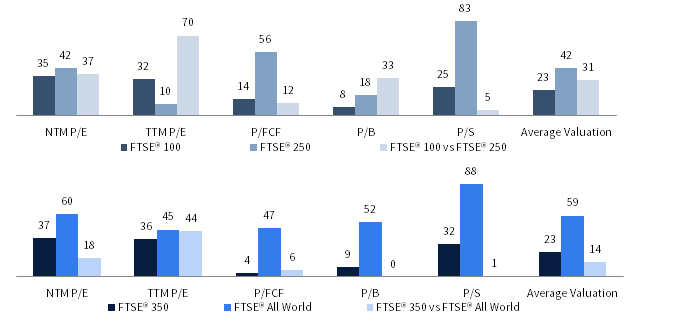

UK equity valuations are currently below their historical average levels and also appear cheap relative to developed markets equivalents (Figure 8), but this is primarily due to historically wide valuation spreads with US stocks. Below-average valuations partly reflect that UK equities have been a consensus underweight among foreign investors for some time. The upshot is that the UK market also offers the highest aggregate dividend yield of any major market. Yet historically, UK equities’ above-average yields have also meant that their relative performance has been negatively correlated with global bond yields. Within the UK market, relative valuations between UK large caps and mid-caps are slightly below average, however UK large caps’ higher dividend yields and greater international revenue tilt could cause them to lag mid-cap stocks if the domestic growth outlook improves, particularly under a more benign Brexit scenario.

FIGURE 8 ABSOLUTE AND RELATIVE UK EQUITY VALUATIONS

As at 28 February 2019 • Historical Valuation Percentile (%)

Sources: FactSet Research Systems, FTSE Russell, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Valuation metrics are represented by: next 12-month price-to-earnings ratio (NTM P/E), trailing 12-month price-to-earnings ratio (TTM P/E), price-to-free cash flow ratio (P/FCF), price-to-book value ratio (P/B), and price-to-sales ratio (P/S). Valuation percentiles calculated from July 1996 to present for FTSE® 100 Index, FTSE® 250 Index, FTSE® 100 Index vs FTSE® 250 Index, and FTSE® 350 Index, and from July 2000 to present for FTSE® All World Index and FTSE® 350 Index vs FTSE® All World Index. Average valuation is a simple average of the valuation percentile of the six metrics shown.

While the UK equity market’s diverse revenue mix limits exposure to adverse Brexit developments, other structural characteristics are less desirable and have also contributed to its low valuations and lack of interest among foreign investors. It is heavily tilted to industries facing disruption (together financials, energy, and basic consumer goods are more than 50% of the market), and there is limited exposure to those doing the disrupting (technology exposure is tiny, particularly to internet software and services). The UK market is also quite concentrated in slow-growing names.[6]Please see Jean-Maurice Ladure, “Brexit and the Risks of Home Bias,” MSCI, 11 January 2019. In terms of the near-term earnings outlook, the sell-side consensus pencils in year-over-year EPS growth of just 3% this year and 8% next for the FTSE® 350, a couple of percentage points below the estimated growth rates for global equities in aggregate.

Though both the ongoing Brexit uncertainty and the external growth backdrop continue to cloud the UK outlook, the risks associated with an orderly Brexit and a broader global slowdown seem to have now been mostly priced in, so investors should not look to underweight UK equities at this time. Yet, relative price momentum between UK equities and other developed markets remains negative. While valuations for UK equities relative to US stocks now appear compelling, UK stocks are not yet cheap enough to merit an overweight allocation versus global equivalents on a standalone basis. Under “no-deal” Brexit scenarios, stocks with high domestic sales exposure and companies that import large proportions of their raw material inputs would be most vulnerable, but all sterling-denominated risk assets would face selling pressure—including equities of UK-listed multinationals with little to no domestic revenue exposure. Thus, an adverse Brexit shock could present an opportunity to add exposure to some good quality, globally oriented businesses at attractive valuations.

Should UK Investors Adjust Their Overall Exposure to Sterling in Anticipation of Brexit?

We believe sterling-based investors should not change their currency hedge ratios or policy weighting to sterling-denominated assets based on potential Brexit outcomes. Few investors have an edge in predicting political processes like these, and for most, hedge ratios should factor in spending and liquidity needs, institutional risk tolerance, and cost of hedging, rather than expected currency movements. Today, it is expensive to hedge USD exposure back to GBP given high US cash yields relative to those in the United Kingdom. However, this negative carry is somewhat offset by the positive carry associated with hedging euro, yen, and Swiss franc exposure back to sterling.[7]Sterling has historically been a somewhat pro-cyclical currency, so maintaining some exposure to other currencies (including traditional “safe havens” such as the yen and US dollar) has helped to … Continue reading

Some UK investors with high levels of sterling spending or income-only spending rules tend to tilt their portfolios more toward sterling-denominated assets. Home country bias obviously increases an investor’s exposure to potentially poor economic outcomes in the home market. These investors should ensure their sterling asset exposure is well-diversified among domestic asset classes, as returns will diverge sharply depending on the Brexit outcome. Sterling cash, gilt, and linker yields are paltry today, but all could offer important ballast to any sterling-denominated asset portfolio if the United Kingdom and EU cannot come to terms on Brexit. In contrast, UK property appears to offer the most attractive absolute yields, but is heavily exposed to adverse Brexit scenarios due to its fully domestic exposure, and London office and retail properties would be most vulnerable. Market prices for UK equities and credits would also suffer in the immediate aftermath of a “no-deal” Brexit; however, their underlying exposures are partially hedged, given the significant presence of globally oriented multinationals in these indexes. Therefore, their yields may be more resilient in an adverse Brexit scenario. As a result, income-reliant UK investors whose portfolios are the most heavily biased toward sterling-denominated assets must be cognizant of Brexit-related risks and should ensure to diversify these important sources of income accordingly.

Conclusion

Though developments and headlines associated with the United Kingdom’s Article 50 negotiations with the EU to exit the trading bloc have been fitful, their impact thus far on the underlying fundamentals of the UK economy and sterling-

denominated assets, particularly UK equities, has been moderate. Because Brexit is a political process with two-way tail risks, it warrants close monitoring, but is not a good foundation for a tactical investment position. Despite the fraught political dynamics, it remains more likely than not that the United Kingdom and the EU can accomplish an orderly withdrawal. In addition, a meaningful adjustment has already taken place, particularly a large depreciation in the British pound.

We continue to believe that investors should be modestly overweight global ex US stocks (including globally oriented UK equities) relative to US equities, given today’s historically wide spreads between US and non-US valuations. Regardless of the ultimate outcome of Brexit negotiations and its future impact on the domestic economy, the UK equity market is fundamentally somewhat insulated from an adverse Brexit scenario because of its international revenue tilt. In addition, valuations are undemanding, and foreign investors are already underweight, providing some protection in a downside scenario. Despite reasonable valuations, UK equities are not yet cheap enough in absolute terms to justify an overweight relative to other non-US equivalents, and with UK stocks’ defensive attributes, they likely would lag global peers in a scenario where external growth and inflation surprised on the upside. Similarly, UK large caps would likely underperform more domestically oriented mid- and small-cap stocks in a softer Brexit scenario in which the home economy improves.

Brexit should not drive decisions on currency hedging. Instead, UK investors should continue to ensure their portfolios are adequately diversified, while maintaining sufficient liquidity and domestic currency exposure to meet anticipated spending needs and to be positioned to take advantage of any future Brexit-driven market dislocations. When determining an appropriate hedge ratio, institutional risk tolerance and the cost of hedging must also be considered. UK investors whose spending is heavily reliant on earning sterling-denominated income need to be mindful of the potential impacts of an adverse Brexit scenario on the various domestic asset classes generating that income and diversify accordingly.

Michael Salerno, Senior Investment Director

Dan Day, Senior Investment Associate

Graham Landrith, Investment Associate

Index Disclosures

FTSE 100® Index

The FTSE 100® Index is a capitalization-weighted index of the 100 most highly capitalized companies traded on the London Stock Exchange. The equities use an investability weighting in the index calculation. The index was developed with a base level of 1,000 as of December 30, 1983.

FTSE 250® Index

The FTSE 250® Index is a market capitalization–weighted index consisting of the 101st to the 350th largest companies listed on the London Stock Exchange.

FTSE 350® Index

The FTSE 350® Index represents large and mid-cap stocks traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), which pass screening for size and liquidity. The FTSE 350® index is made up of the constituents of the FTSE 100® and FTSE 250® index.

FTSE All World Index

The FTSE All World Index is a market capitalization–weighted index representing the performance of the large and mid-cap stocks from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series and covers 90-95% of the investable market capitalization. The index covers Developed and Emerging markets and is suitable as the basis for investment products, such as funds, derivatives and exchange-traded funds.

FTSE All World Developed Markets Index

The FTSE All World Developed Markets Index is a market capitalization–weighted index representing the performance of large and mid-cap companies in developed markets. The index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS), which covers 98% of the world’s investable market capitalization.

Footnotes