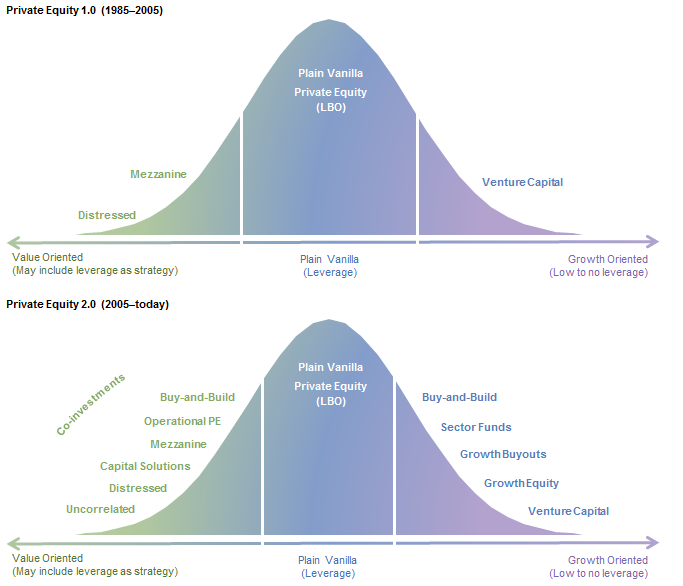

The term “private equity” covers a wide variety of investment strategies, from distressed debt to venture capital. What the strategies have in common is that they involve private, illiquid investments rather than publicly traded stocks, and investors are generally privy to information not otherwise available to the public. Leveraged buyouts (referred to as LBOs or simply buyouts) are the largest private equity strategy by capital, and, along with venture capital, the most well-known strategy within private equity. Modern buyout investing began in the 1980s when some of today’s largest firms—such as Bain, Blackstone, Carlyle, and KKR—were created, and one of the most notorious deals, RJR Nabisco,[1]In 1985, RJ Reynolds (tobacco) acquired Nabisco (food products) in a merger worth $4.9 billion; the RJR Nabisco buyout took place three years later. Depicted in the book and movie Barbarians at the … Continue reading was completed. Interest in buyouts ebbed in the mid- and late 1990s, but grabbed the spotlight again beginning in 2005 when the first “mega funds” (funds with $10 billion or more in assets) were raised, helping to fuel the largest vintage years in history in 2007 and 2008. With the growth of the industry, investment strategies under the private equity umbrella have become more diverse (Figure 1).

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

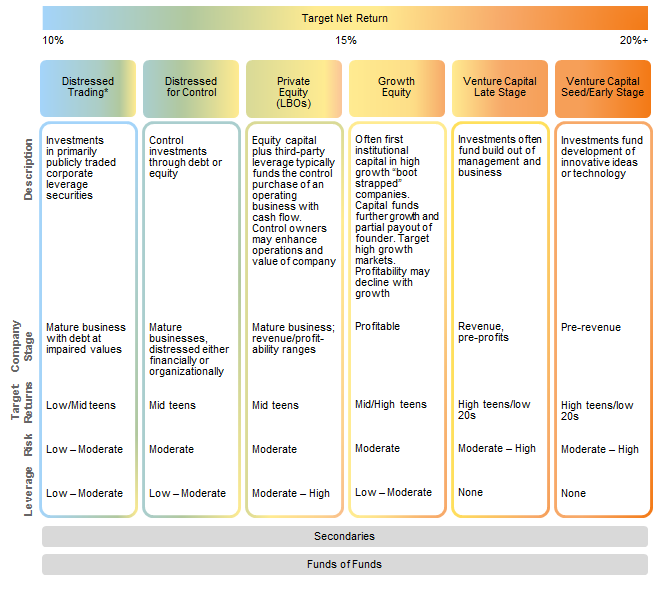

Today’s private equity firms are increasingly differentiating themselves through sourcing, financing, analyzing, and operating companies, as well as through sector specialization. For example, while traditional buyout funds primarily targeted companies in industries that produced predictable cash flow (like manufacturing), starting in the late 1990s, funds were formed to focus on the technology sector given the industry’s maturation during the decade. Today, a number of funds specialize in specific sectors, including consumer, energy, financial services, health care, and technology. Figure 2 describes the spectrum of private equity strategies in more detail.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

* Exposure can be gained through hedge funds.

In this report we discuss LBO strategies in depth and touch on distressed and growth equity strategies. We review types of buyouts, the buyout investment process, returns, fees, risks, and recommendations for conducting due diligence.

In short, buyout managers (often called GPs for general partners) generally invest in mature companies they deem undervalued, with the aim of improving them and then selling for a profit. Purchases are funded with a combination of equity and debt (“leverage”), which can help boost returns to the equity investor. Investments are typically exited through a sale to a strategic or financial buyer or through the public markets via an initial public offering (IPO). Investors in buyout funds, called limited partners (LPs), commit during the fund-raising period, contribute capital as the fund “calls” it for investments, and receive capital back when investments are sold and the GP distributes capital from the proceeds.

Multiple risks are associated with all private equity investing, including buyouts. Illiquidity and blind pool risk, discussed in this report, could be a concern for LPs, and many factors contribute to the success or failure of an investment, including issues specific to the target company, the purchase price, sector, geography, and macroeconomic environment. Healthy exit environments (active merger & acquisition activity and strong public markets) also help to drive positive exits for buyout funds. Before committing to a buyout fund, potential LPs conduct due diligence on the investment opportunity, focusing on the firm and fund managers, the fund’s investment strategy, investment performance, and fund terms.

What Are Buyouts?

In a leveraged buyout transaction, a fund buys the equity or the assets of a company for a negotiated price, using a mixture of equity and debt, otherwise known as applying leverage. The debt portion of the transaction includes senior secured debt supplied mainly by banks (willing to lend because LBO targets have steady cash flow and because the banks have a claim on the underlying assets of the business), as well as high-yield debt and debt with equity characteristics such as convertible debt, stock, or warrants. Buyout funds target more established companies than their venture capital counterparts and focus on improving operations, often by cutting costs, selling unprofitable businesses, and recruiting key executives. Targeted businesses typically have enterprise values between $100 million and $10 billion (a range that changes over time), and investments are generally sold to strategic or financial buyers or taken public through a public stock offering.

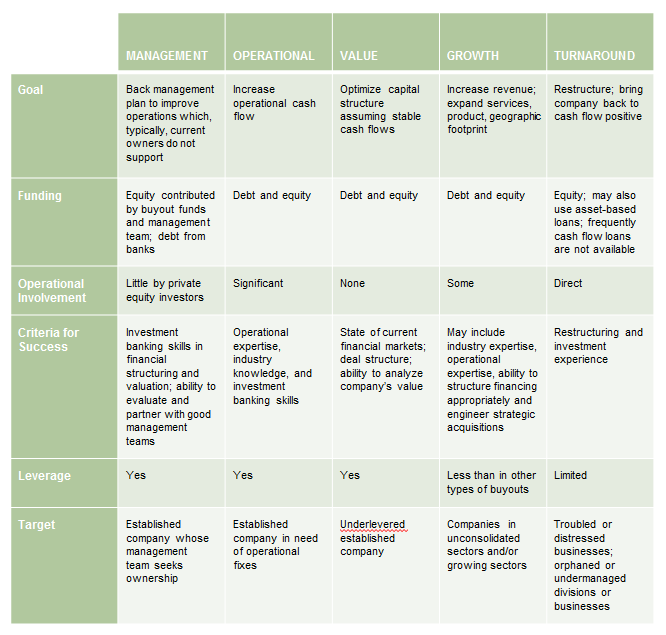

Types of Buyouts. The five main types of buyouts include management buyouts, operational buyouts, value buyouts, growth buyouts, and turnarounds. Figure 3 summarizes their key characteristics.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

In a management buyout, company management and a private equity fund buy the company from the existing owners with the intention of implementing the management team’s plan to operate the business more effectively. In this type of buyout, the interests of the management team and the buyout fund are aligned.

In an operational buyout, the private equity fund managers and/or their operating partners/proxies become directly involved in the operations of the portfolio company. The goal of such involvement is to increase the cash flow produced from the company’s operations through various strategies, such as creating efficiencies and cutting expenses through reduction in workforce. This type of buyout requires buyout professionals with specific operating experience and knowledge of various industries.

In a value buyout, the GP does not become involved in the operations of the portfolio company. A value buyout is a pure financial play where the buyout fund expects to benefit from applying leverage to a company and lowering the cost of capital, which should increase the cash flows to the equity owner. The success of a financial buyout is largely dependent on current financial markets, the structure of the deal, and the ability to analyze the value of the company.

In a growth buyout, the private equity fund seeks to capitalize on growth in the revenues of the portfolio company. These funds often seek to create revenue growth through market share gains, overall market growth, distribution or product line expansion, and market consolidation and acquisitions. Targeted companies are generally less mature than in more traditional buyout transactions. Skills required often include the ability to offer operating enhancements, engineer strategic mergers, or structure financing for the growth of the company.

In distressed and turnaround investments, the private equity fund typically acquires control in troubled or underperforming companies or divisions with the goal of improving the company’s cash flows. Targeted companies might be good companies with bad balance sheets, such as in a distressed-for-control transaction, when the company is no longer able to service its debt. In this case, the turnaround (or distressed) fund purchases the fulcrum security—which is the part of the company’s capital structure that will control it after a reorganization, usually in the form of equity (though identifying the fulcrum security’s location in the capital structure is not a straightforward task)—and works through the restructuring process as a key member of the creditor committee. This committee typically leads the process to restructure the balance sheet, with the investors in the fulcrum security typically receiving equity as well as some debt in the restructured company. Turnarounds are similar to operational buyouts but with more severe cash flow problems. In many cases, portfolio companies can be acquired at below liquidation value (value of assets). Other examples of turnarounds could involve businesses in need of restructuring due to an outdated business model (e.g., brick-and-mortar retail facing online competition) or workforce issues including labor/union contracts and pension plans that burden the company from a cost standpoint. Skills generally required for turnaround funds include restructuring, legal, and investment experience.

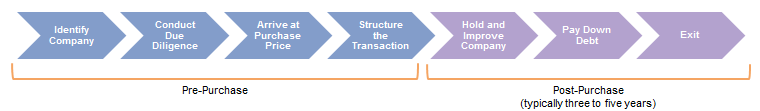

The Buyout Investment Process

Regardless of the type of buyout, all buyout funds generally follow a similar process, depicted in Figure 4.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

The first step in the investment process is deal sourcing, or identifying a company, which can be done through proprietary channels or auctions. Firms that focus on small- and mid-cap companies tend to use proprietary sourcing, such as cold calling, database mining, and industry conferences, while funds focused on large- or mega-cap companies are more likely to find opportunities through auctions run by investment banks. Funds target a range of companies, from privately owned companies to public companies (divisions, subsidiaries, or entire companies) that they will take private. Targets generally share characteristics like undervaluation, largely unlevered balance sheets, strong management, valuable assets, and predictable cash flow.

Once a company is identified, the buyout fund will conduct due diligence, focusing on items such as the company’s market position, management, and financial performance. Through this analysis and financial modeling based on growth and performance assumptions, the fund will arrive at a purchase price. The next step is to structure the transaction using debt and equity to optimize the capital structure.

Post-investment, private equity firms seek to improve the portfolio company’s performance primarily by growing revenue and EBITDA, increasing operating margins, and helping to generate free cash flow that could be used to service and pay down the new debt. While under private ownership, changes are often made to management and operations, such as sales and business strategies. Private equity firms typically hold their companies for three to five years, depending on market conditions and the performance of the company.

In the final stages of the process, prior to exiting the investment, debt is paid down as free cash flow improves, both because of the amortization requirements of the loans and to prevent cash building up on the balance sheet, which is not an optimal use of funds. In this instance, the private equity fund might seek to issue dividends to the equity owners, depending on the terms of the financing, which might require debt paydown prior to paying dividends. Invest-ments are exited through a sale to a strategic or financial buyer or a public offering.

Buyout Firm Investment Strategies

Buyout strategies have evolved from the “plain vanilla” buy-and-build investment approaches of the past. In today’s market, funds rely on more than financial engineering and cutting costs. Firms differentiate themselves through sourcing; growth or value orientation, sector, market, and geographical expertise; and operational experience. A buyout fund’s investment focus can be characterized along a few simple dimensions.

Portfolio company size. One of the key differentiators among buyout strategies is the size of the targeted companies. While the ranges for what are considered small, middle, and large companies have shifted over time, in general, small-cap companies are up to approximately $250 million in enterprise value (the value of the company’s equity, debt, and cash), mid-cap companies have enterprise values up to $1 billion, and large-market companies are larger than $1 billion in size. In addition to enterprise value, other metrics used to determine a company’s size might be EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) or revenue.

Fund and investment size. Funds are typically categorized by the average size of their equity investments, as well as the amount of money committed to the fund. For example, smaller funds might invest as little as $5 million of equity into deals and can be as small as $100 million in committed capital. Mega funds could invest more than $1 billion in a transaction and have been as large as $20 billion in commitments.

Growth or value. As discussed, typical buyout funds invest in undervalued companies and sometimes in businesses that require significant change or “turnaround.” On the other hand, growth-oriented funds invest in profitable companies whose revenue and EBITDA are growing by 20% or more. Similar to leveraged buyouts, growth-oriented funds vary in size, with corresponding differences in the market capitalization of the target companies.

Sector specialist versus generalist. Buyout and growth-oriented funds are increasingly specializing in individual sectors rather than implementing more opportunistic strategies. Today, there are sector-focused funds dedicated to a variety of sectors, such as business and financial services, consumer, energy, health care, and IT. A fund manager’s specialization might also be geographic in nature, such as Nordic region, midwestern United States, or Latin America, although larger firms tend to have global mandates.

Operational focus. Private equity managers have moved away from financial engineering and toward operational expertise. GPs now have a wide variety of experience among their investment teams. In addition to former investment bankers and other investment professionals, GPs may be former company executives, business development professionals, medical doctors, and other types of sector experts. Another tactic for funds is to build “benches” of experts to help improve companies once they are acquired.

Buyout Returns

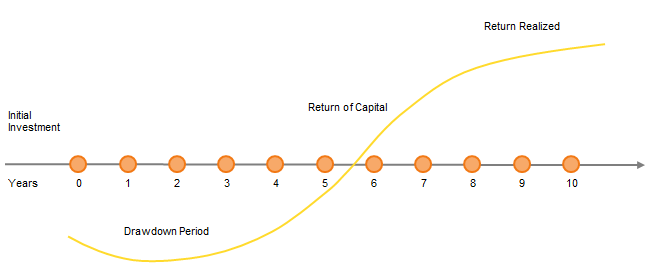

Private equity funds are blind pools (i.e., the individual investments are not identified prior to the LP’s commitment) “raised” with capital commitments in a fund-raising process. LPs commit capital to private equity partnerships formed by a GP, or the investment team/manager of the fund. When the GP identifies an investment, it “calls” capital from the LPs. When the GP exits or sells an investment, it “distributes” the proceeds from the transaction to LPs. The life of the partnership is generally ten years with the potential for extensions. The first three to six years of the partnership’s term is the investment period when most of the committed capital is called (or drawn down). Figure 5 illustrates the effect on returns caused by the cash flow trajectory of LP contributions (capital calls and fees) in the early years of a partnership followed by LP distributions in later years.[2]In the first few years of a fund, returns are usually negative as a result of the LP contributions and fund expenses, coupled with less movement in the valuation of portfolio companies. Later in the … Continue reading

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Note: Illustrative cash flow is calculated from the Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Exposure Model, based on a starting total pool value of $800mm and 2% pool growth rate.

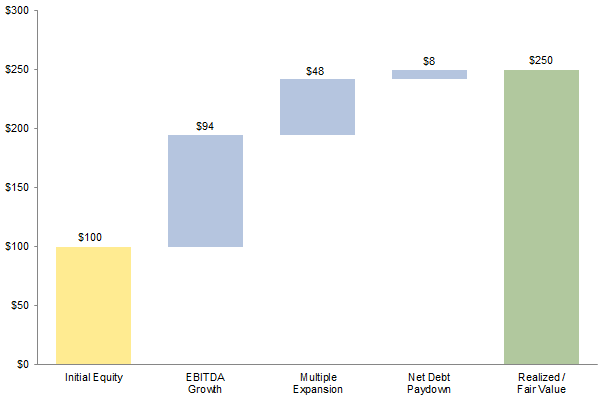

Buyout returns are driven by the initial price paid and degree of leverage employed, the holding period, the economic success of the business during the holding period, and the company’s market value at the time of sale. The health of the public markets and the merger & acquisition market both factor in to the buyout fund’s ability to sell the company and realize a return. Buyout funds can also boost returns through improving the company’s operations (revenue, EBITDA, margins) or selling undesirable or nonessential divisions. Earnings growth should lead to increased value for the company, and proceeds from selling divisions could be used to pay down debt or invest in strong performing operations.

Figure 6 further illustrates the various components of value creation in an LBO transaction. The first bar refers to the equity contribution of the company’s purchase price and the last to the equity value realized at exit (when the fund sells the company). The difference between the last bar and the first is the value created (or return), in this case $150, which is composed of the middle three bars: EBITDA growth, multiple expansion, and net debt paydown. In this example, EBITDA growth contributed $94 of the $150 return. Multiple expansion, or the GP’s ability to sell the company at a higher EBITDA multiple than it paid at acquisition, contributed $48 of return. When EBITDA has increased during the holding period and the multiple at exit is higher than that paid at acquisition, multiple expansion is a larger component of the value created by the private equity fund. By paying down debt, the private equity fund increases its equity in a company.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Fees

GPs are compensated through two types of fees: the management fee and their share of profits, known as carried interest or carry. For many funds, the fee structure tends to peg management fees at about 2.0% in the funds’ investment period. Following the investment period, fees typically transition from being based on committed capital to being based on the amount invested in portfolio companies. The carried interest charged by funds varies, with 20% a frequently used amount. Many funds include a “hurdle rate” for their carry. Hurdle rates require the fund to earn a minimum return to LPs, only after which does the GP receive the specified carried interest.

Risks Associated With Private Investments

A number of risks are associated with private equity strategies, including buyouts. For example, investments are illiquid for a number of years, and most types of private investments offer little or no current income flow. As a result, the return is dependent on the eventual sale of the company, the return of the GP’s cost basis (i.e., the current investment amount), and the realization of capital gains. The use of leverage also presents risks, making the investment more vulnerable to changes in the financial markets (e.g., rising interest rates and/or declining valuations). Buyouts predicated on the restructuring of operations will tend to be less exposed to shifts in the financial markets, with the primary risks arising from macroeconomic conditions and industry- or company-specific factors, such as regulatory changes, increased competition, or product obsolescence.

Another component of risk in an LBO or private equity investment is the purchase price, or how much a fund pays for an asset. Various scenarios can drive purchase prices too high and result in lower-than-expected returns. For example, if assumptions used to calculate the purchase price prove incorrect (or too optimistic), the fund will have paid too much and will be at risk of losing money upon exit (realizing less money upon exit than was paid at acquisition). Valuations (purchase prices) can also become inflated when the LBO market overheats, as seen in the period leading up to the global financial crisis in 2008. Cheap credit, an intermediated market (investment banker–led auctions), increased merger & acquisition activity by strategic buyers, and strong public markets can all contribute to an increase in competition for deals and concomitant increases in valuations (prices).

We discuss the current environment, valuations, and our views on investing in various private equity strategies in our monthly Asset Class Views publication.

When assessing market conditions for private equity, investors look at the pace of the industry’s fund raising, capital calls, and distributions. Exogenous factors, such as the health of the public markets and the availability of credit, influence all stages of the private equity investment process and cash flows.

Due Diligence

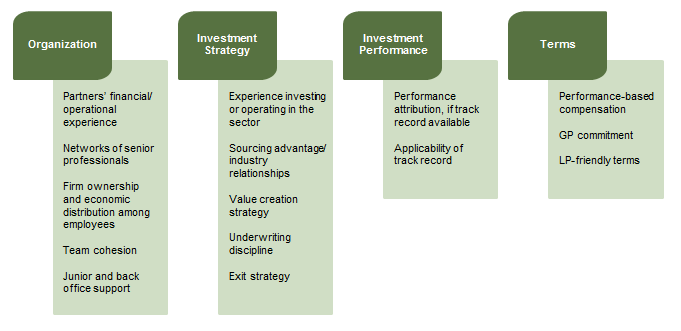

The investment due diligence process for buyout opportunities (and private equity strategies more generally) focuses on the following key components: organization, investment strategy, investment performance, and fund partnership terms. Each of these is discussed in more detail in the text that follows, and Figure 7 summarizes some of the items evaluated during due diligence. Cambridge Associates recommends LPs view each fund as a new opportunity that should be diligenced in the same way as prior funds have been—i.e., a decision to invest in Fund IV should not automatically be a decision to invest in Fund V.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Organization. When assessing the organization, a potential LP evaluates the firm history, the experience and compatibility of the investment team (GP), the ownership and economics of the firm for its employees, and the investment process. Questions asked during this phase of due diligence focus on the strengths and weaknesses of the investment team, the appropriateness of the team’s experience to its strategy, and the specifics of the investment process.

Established buyout firms are generally managed by a group of GPs that have worked together in the buyout business and can document their success in previous investments. Since established firms tend to be some of the largest, they control the greatest amount of capital raised and so the majority of private capital continues to be managed by experienced managers. Many new funds, particularly those that are spinouts from larger firms, are also led by GPs with substantial principal-investing experience.

Although LPs may feel more comfortable with an experienced group raising a follow-on fund, they should ensure that the individual partners primarily responsible for particularly winning investments remain on board. In addition, careful questioning of the partners may reveal that the actual screening and analysis is now being performed by new, less experienced associates in the firm. If less experienced associates and junior partners are involved in decision-making at the larger firms, LPs should understand fully the extent to which critical decisions are still made by the most experienced partners.

Evaluation of the GPs’ experience is much more difficult in the case of emerging managers. Knowledge of how long and in what capacities the partners have known each other is crucial, because the ability to work well together is critical to the success of the partnership. To the extent members of the new team have buyout experience, LPs should diligently identify the investments for which those individuals were responsible and the ensuing results. LPs should also assess whether the new team has the skills needed for success. Among these are the financial experience required both to assess the pricing structure of a deal and to assist the company’s management during a period of enhanced financial risk; experience in operations and marketing, which will be needed not only to evaluate the business prospects of the potential investment but also to assist in those areas during the period of investment; and, finally, the industry expertise needed to analyze the potential investment and to provide access to deal flow.

Investment Strategy. The next element of the due diligence process is an evaluation of the investment strategy, including deal sourcing, pricing discipline, sector expertise, structuring capabilities, value creation strategy (post-acquisition actions), and exit strategies. Questions about investment strategy focus on the partnership’s ability to execute the strategy in the past, the repeatability of its sourcing process, and its purchase price multiples (purchase price/EBITDA) relative to peers and public companies.

Probable deal size (and, relatedly, whether targets will tend to be public or private and large- or small-cap), industry emphasis, geographic concentration, and whether the financing will be concentrated in equity or debt all directly affect the level of risk and potential return of a given fund. Consequently, prospective LPs should analyze the extent of a fund’s diversification in these critical areas to understand how much risk the fund intends to incur. In addition, potential LPs cannot effectively assess the GPs’ ability to add value without a thorough understanding of how the proposed strategy is designed to exploit the specific experience and expertise of the buyout firm’s personnel.

Lastly, for either established or emerging managers, the individual elements of the partnership must coalesce into a cohesive team and strategy. Do the individual partners’ levels of experience, the profile of their earlier partnerships (if an established firm), the makeup of the management team, the size of the fund, and the probable source of their deal flow mesh with their proposed investment strategy?

Investment Performance. A review of the firm’s investment performance at the fund and company levels is another critical part of the due diligence process and helps to inform a view on performance consistency and the manager’s ability to replicate returns in the future. In this stage, potential LPs review performance, internal rates of return, multiples on invested capital, and total value created in both absolute terms and relative to peers. Both gross (before fees) and net (after fees) performance are analyzed and compared to other private equity funds and the public market indexes. At the company level, performance is evaluated from both an investment and operational perspective. The investment evaluation looks at many aspects of returns, including consistency, range of outcomes, concentration, loss ratios, sector performance, partner attribution, and realized versus unrealized valuations. The operational review is based on revenue growth, margin improvement, EBITDA growth, and purchase price and leverage multiples, which is one part of assessing the “riskiness” of the investments.

Terms. The last stage of due diligence is a review of LP terms and how they compare with industry standards. The terms review, along with an operational due diligence (an assessment of the people, processes, and controls in areas such as compliance, fund accounting, trading operations, and technology), highlights potential areas of negotiation between LPs and GPs. Among the more important terms a prospective LP should look for are strong alignment of LP and GP interests, high GP commitment (dollars invested in the fund), management fee offsets (the extent to which monitoring, transaction, and other portfolio company–related expenses paid to the GP are offset against management fees), appropriately sized funds, and strong key person and no fault divorce clauses (terms that offer LPs protection in the event of the departure of key GPs, the removal of the GP, or the end of the partnership altogether).

Caryn Slotsky, Senior Investment Director

Other contributors to this report include Andrea Auerbach, Keirsten Lawton, and Christine Trang.

Footnotes