Please see Sean McLaughlin, “Long Muni Bonds: Unloved, Orphaned, and Perhaps Safer Than You Think,” Cambridge Associates US Market Commentary, March 2011.

Some muni bondholders in 2011 were terrified by a sky-is-falling prediction when Meredith Whitney, who made her name with a prescient call on bank shares during the lead up to the financial crisis, blustered that at least fifty large municipal issuers would default within 12 months, racking up hundreds of billions of dollars in losses. We pushed back hard on this prediction and suggested that investors should use the market’s fear as an opportunity to load up on long-maturity muni bonds. Since then, yields on these bonds have collapsed,[1]Yields rose sharply in November, in concert with the yields on Treasury bonds, but they remain nearly 2 percentage points below early 2011 peak levels. and the Bloomberg Barclays 20-Year Municipal Bond Index has returned an annualized 5.8% from March 2011 through November 2016.

The key risk we laid out in our 2011 paper was that state and local pension liabilities were a significant long-term concern, and that investors in long-term muni bonds faced considerable risk if pension liabilities were not dealt with soon. While Whitney’s default predictions were and are outlandish, under-funded municipal pensions deserve more attention today from municipal bondholders. The window is open for plans, states, or perhaps even federal regulators[2]Any federal role in setting up a municipal equivalent of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation would likely be controversial, and it is difficult to imagine this development absent a crisis. to act before the market panics, but the required action will be painful and deeply unpopular with voters, increasing the likelihood that necessary action will be deferred until it’s too late.

In this brief, we review recent dynamics in public pension liabilities and discuss why municipal bond investors, especially those with large allocations, will want to follow developments in city and state pension markets, if they are not doing so already.

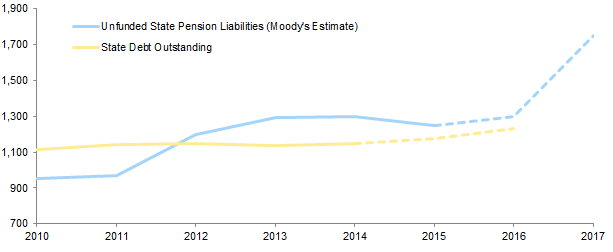

Unfunded Pension Liabilities Zoom Higher

Unlike corporate pension plans, public plans typically determine the current value of their future benefit payouts by discounting them using a long-term investment return assumption. Most public plans assume that their returns will be 7.5% to 8%.[3]The board of California’s giant CalPERS plan may vote as early as February on whether to significantly lower CalPERS’ assumed return. For more on this, please see Imogen Rose-Smith, “How Low … Continue reading Returns of course fell well short of that mark in the past two fiscal years. The median public plan returned 1.1% in the fiscal year ended in June, according to the Wilshire TUCS database. Given lofty current valuations for stocks and bonds, the long-term return prospects for these plans are not appreciably better. The weak recent returns, combined with contributions that are below sustainable levels, have increased pension funding shortfalls, and they are expected to grow even further in 2017. Moody’s calculates that adjusted pension shortfalls for state plans alone have risen from a bit less than $1 trillion in 2010 to $1.25 trillion in 2015, and the firm estimates deficits will get to $1.75 trillion by 2017. (The Moody’s estimates are significantly larger than official figures offered by municipal governments, because Moody’s uses the lower discount rates associated with yields on long-term corporate bonds, similar to the way corporate pension plan liabilities are calculated). To put that in context, the entire Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index of investment-grade bonds totals only $1.4 trillion. So, unfunded pension debt of municipal issuers—only barely on the radar of most investors—is of a similar scale to the total bonded debt outstanding for these issuers! Imagine if the average American household had a credit card balance as large as the household’s mortgage—a balance that grew each year, with payments that rarely covered the growth in outstanding liabilities—and that the credit card debt was disclosed to the household’s other lenders in a way that made it appear vastly smaller than its true size.

Unfunded Pension Liabilities vs Outstanding Debt for US State Governments

2010–17 • US Dollar (Billions)

Sources: Barclays, Bloomberg L.P., Moody’s Investors Service, and US Census Bureau.

Notes: Pension liabilities in this case refers to adjusted net pension liabilities (unfunded liabilities), as estimated by Moody’s, including various adjustments and lower discount rates than are currently required by law or accounting convention for municipal pensions. Both the unfunded pension liabilities and the total debt outstanding include only a portion of US municipalities. State debt outstanding includes both short-term and long-term debt issued at the state level. Dashed lines are estimates. Total debt outstanding estimates for 2015 and 2016 calculated by increasing the 2014 level of total debt outstanding by the same percentage as the increase in the total market value of the 50 states in the Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index. Both figures exclude the US territories of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, as well as the District of Columbia.

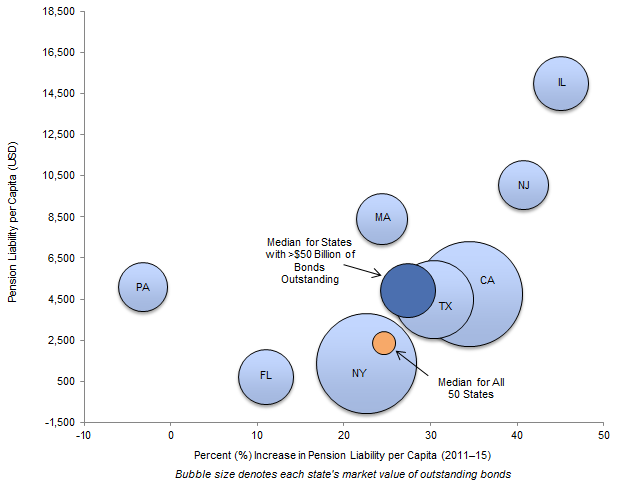

Not All Issuers in the Doghouse

The deficits differ substantially from state to state. From 2011 to 2015, unfunded pension liabilities actually shrank in 14 of the 50 states, while the states with the largest amounts of outstanding municipal bonds (those shown in the figure below) saw their liabilities grow by a median of 27%. The three states with the largest deficits—California, New York, and Texas—grew between 20% and 35% during the period, while the already large Illinois deficit expanded by 45%.[4]The deficits of these three states are large on an absolute basis, but this is partially due to large populations; per capita deficits are in the ballpark of the 50-state median level of $2,400 per … Continue reading

Just as growth rates vary by state, per capita liabilities do as well. North Carolina, which is almost fully funded, has an unfunded liability of just $589 per capita according to Moody’s. Residents of the median state have a $2,400 unfunded liability per capita. The pension deficits of Connecticut and Illinois each total nearly $15,000 per capita (22% and 30% of personal income, respectively).[5]Please see Blake Van Wagner et al. “Medians – Low Returns, Weak Contributions Drive Growth of State Pension Liabilities,” Moody’s Investors Service, October 6, 2016.

Sources: Barclays, Bloomberg L.P., and Moody’s Investors Service.

Notes: The states selected for display are the eight states with greater than $50 billion of total market value outstanding in the Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index. Pension liabilities per capita in this case refers to adjusted net pension liabilities per capita, as estimated by Moody’s including various adjustments and lower discount rates than are currently required by law or accounting convention for municipal pensions.

The reported liabilities would appear substantially smaller if calculated using the overly optimistic (but legal) 7.5% or greater discount rates that are commonly employed by states for disclosure purposes, rather than using corporate bond yields, as corporate plans do.[6]The recent introduction of new GASB accounting rules helped to standardize the reporting across issuers, but only the issuers with very low funding levels are required to move to realistic bond-based … Continue reading However, portfolio managers and ratings agencies often look past the overly rosy funding reports that stem from using high discount rates and instead use more realistic discount rates that often substantially increase the reported shortfalls. The unfunded liabilities estimated by Moody’s in the first two figures, for example, are discounted using yields of high-quality corporate bonds. To get a very rough sense of the varying liability picture, investors might multiply two factors together: (1) the 2.9% difference between 7.5% assumed returns and 4.6% long corporate yields, and (2) the 14-year duration of the long corporate bond index. Under the more conservative approach employing bond yields, the liability is perhaps 40% higher than under the standard approach.[7]The Moody’s report was published in early October; yields of long corporate bonds have risen by about 50 basis points since then, which is a large increase but likely not enough to materially … Continue reading Members of a pension appraisal trade group began feuding in the media this fall when the group’s own task force tried to publish a white paper arguing that pensions should adopt more conservative, market-based accounting of liabilities.[8]Appraisers face pressure from public-plan clients to sign off on the use of high discount rates, because more reasonable discount rates would force unpalatably high pension contributions. Please see … Continue reading

Can Troubled Issuers Dig Themselves Out of the Pits?

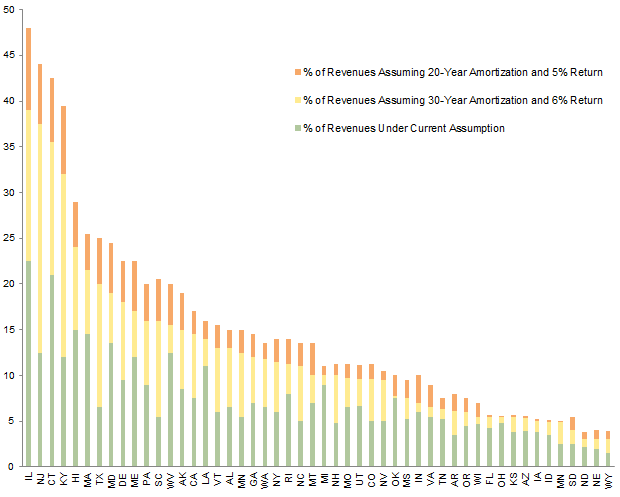

Many municipalities are contributing to their plans at insufficient levels each year, and in the process are digging themselves a deeper hole. If issuers were to ramp up contributions to gradually fund all liabilities, even over the course of decades, the increase in required annual pension spending would be massive. The green bars in the figure below show the percentage of revenues that each state currently spends in total to cover its bonds, pensions, and retiree healthcare benefits.

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Note: Graph also includes revenues required to cover defined contribution plan payments.

While a few states (notably, Illinois and Connecticut) already have difficult-to-manage burdens, the figures are reasonable for most states. However, the yellow bars show the higher level of annual spending required if plans were required to get to fully funded levels over the course of the next 30 years, with a pension discount rate of 6%. About one-fourth of states would need to devote 15% of revenues or more to their bonds and retirees. And if states were to discount liabilities at only 5% and had 20 years of amortization to get back above water, seven states (representing one quarter of the market value of the Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index) would need to devote one-quarter of revenues or more to this effort.[9]These estimates are from Michael Cembalest, “The ARC and the Covenants, 2.0: An Update on the Long-Term Credit Risk of US States,” J.P. Morgan, May 19, 2016. (ARC refers to annual required … Continue reading This is likely impossible. Several states currently do not contribute to their plans even the smaller amount that is dictated by their preferred actuarial method. While the median plan contributed 99% of its required amount in 2013, the weighted average plan contributed only 81% (New Jersey’s and Pennsylvania’s plans contributed about 40% of required liabilities from 2001 through 2013, for example).[10]Please see Keith Brainard and Alex Brown, “Spotlight on the Annual Required Contribution Experience of State Retirement Plans, FY 01 to FY 13,” National Association of State Retirement … Continue reading

J.P. Morgan’s chief strategist Michael Cembalest has estimated the fiscal pain that would be required for the most underwater states to get back above water, even using the more liberal standards of the yellow bars above. New Jersey would need to increase tax revenue by 7.6%,[11]Raising state and local taxes may be one option, but the scope is likely limited because states compete for employers and wealthy residents, and many of their competitors are in decent shape. cut direct spending by 7.1%, and more than double worker retirement contributions; that entire savings would need to be devoted toward making up the pension gap, and this pain would need to continue for 30 years.

Implications for Bondholders

Most muni bonds theoretically should not face a threat from an issuer’s pension collapse. However, theory is one thing, and reality is another. In a bankruptcy, it would not be unusual for bondholders and pension plan members to both be stiffed.[12]Whether an entity is eligible to file for bankruptcy is not a factor in whether bondholders will continue to receive coupon and principal payments—see Puerto Rico. This brief focuses primarily on … Continue reading

If two types of creditors are competing for the available assets of an entity in the midst of a financial crisis, which will fare better—municipal bondholders, or pensioners? About 42% of municipal bonds are held by the wealthiest half of one percent of US households. It seems likely that the retirees—who are generally voters in that community—will be cast in a favorable light and will often receive more substantial recoveries. In four recent city bankruptcies,[13]This analysis looks at Vallejo, Stockton, and San Bernardino, California; and at Detroit. Please see Yvette Shields and Keeley Webster, “Why Pensions Beat Bonds in Bankruptcy Court,” The Bond … Continue reading Moody’s estimates that bondholder recoveries averaged 44 cents on the dollar, while pensioner recoveries averaged 96 cents.

While we believe muni bonds remain a sound investment (one that would be difficult for most taxable investors to easily replace), investors should consider avoiding issuers with significant pension risk: for every profligate Illinois or New Jersey pension plan, a well-funded plan elsewhere mirrors it. The muni bond market is very diverse, and investors and their bond managers are not compelled to own credits that will weaken as pensions come due (particularly if the bonds are not offering adequate incremental yield compensation). Investors should also diversify across credits rather than sticking with a home-state mandate—the incremental after-tax yield that can come from owning solely the bonds of an investor’s home state is not worth the much higher risk of concentrated exposure.[14]Generally, investors do not pay state income tax on bonds issued by their home state, or city income tax on bonds issued by their city. For this reason, it has historically been popular for New … Continue reading And some managers concerned about pension risk have moved to overweight essential-services revenue bonds (like water utility bonds), and to underweight general obligation bonds.

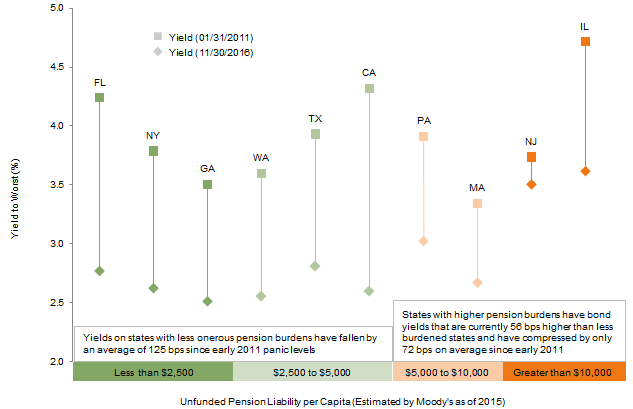

Will bankruptcies of municipal issuers noticeably increase in the next few years? Likely not, even though the mayor of Dallas generated national headlines when he was quoted saying that the city appeared to be “walking into the fan blades” of municipal bankruptcy.[15]The New York Times reported that the city of Dallas had a “hidden pension debt of almost $7 billion.” Please see Mary Williams Walsh, “Dallas Stares Down a Texas-Size Threat of Bankruptcy,” … Continue reading More likely is that a wave of credit downgrades scours the municipal bond landscape, leaving investor outflows and lower bond prices in its wake. Such an event would likely hurt most or all muni bonds initially, but strong credits would recover within months, while weak credits may not. For example, in early November, Standard & Poor’s cut the credit rating of $36 billion of New Jersey bonds, noting that “the current trend of declining pension funded levels could lead to diminished credit quality.” The figure below shows how bond yields have evolved for the ten states with the largest amount of outstanding municipal bonds from January 2011, when muni bonds were in crisis mode, to today. States including Florida, New York, and even California, which have unfunded pension liabilities that appear to be manageable, have seen their bonds recover nicely. On the other hand, for Illinois, New Jersey, and other issuers with very high unfunded pension burdens, bond yields remain somewhat elevated.

Sources: Barclays, Bloomberg L.P., and Moody’s Investors Service.

Notes: Maturity of state indexes shown varies from 11 years to 14 years. January 2011 was a period of elevated yields for municipal bonds amid concerns of default. Moody’s estimates use corporate bond yields rather than high assumed returns as the discount rate, and they incorporate additional adjustments; these estimates are generally larger than those produced by public pension sponsors.

The Bottom Line

Making pension promises to state and local employees is much easier than funding those promises, particularly when boosting pension contributions means either cutting spending or raising taxes (or both). An easier approach is to keep assumed returns high, and hope that actual returns fill the widening chasms. But some municipal bond issuers keep inching toward an eventual pension deficit crisis. Municipal bondholders would do well to pay attention to deficits (and to state and federal efforts to close them, if those efforts get momentum), avoid concentrating in their home state’s bonds (even if their home state’s pensions are well-funded—other single-state issues can surprise investors), and consider managers that can actively steer away from the issuers that are on the rocks or heading toward the shoals.

Footnotes