In this Edition:

- Hedge fund risks continue to draw the interest of US regulators

- Potential new fee reporting template furthers push for private equity transparency

- Federal court ruling creates questions around private fund structures and liabilities

- Comprehensive European Union legislation adds to increasingly complex global regulatory landscape

Hedge Funds Back in the Crosshairs

Task force looks at systemic risk

Adding to the recent hurdles facing hedge funds, US regulators recently announced that they plan to focus on the systemic risks posed by the funds—particularly the large, highly leveraged type. The US Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) has been charged with identifying firms and activities that could create risks to the financial system. FSOC has broad powers to require “enhanced” regulatory oversight of firms or activities it determines pose a risk to the US financial system. As a potential prelude to further regulation, the FSOC has set up a multi-agency task force to complete a report on hedge funds and systemic risk by fourth quarter 2016.

For more on the impact of SIFI designations, see our May 2014 Quarterly Regulatory Update.

To date, FSOC has taken action with respect to large banks and several large non-bank financial institutions, designating them as “systemically important financial institutions,” or SIFIs. Receiving this designation is not trivial; General Electric (GE) was designated a SIFI in 2013 and has since sold, spun-off, or discontinued more than half of the assets owned by its GE Capital arm in a bid to reduce the company’s exposure to financial markets. At the end of first quarter 2016, GE Capital had shrunk by $284 billion, and GE requested that FSOC rescind its SIFI designation. Relatedly, insurance giant MetLife recently won the first round of what may be a protracted litigation challenging its SIFI designation.

See the February 2016 edition of Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on these SEC initiatives.

While asset management firms have so far escaped company-specific SIFI designations, regulators’ systemic risk concerns are nonetheless having an impact. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has already proposed rules addressing systemic risks around specific activities including mutual fund liquidity and use of derivatives. Super-regulator FSOC remains focused on similar issues, recommending that other US regulators consider taking steps to reduce systemic risks associated with illiquidity and “first mover” advantages in the asset management industry.

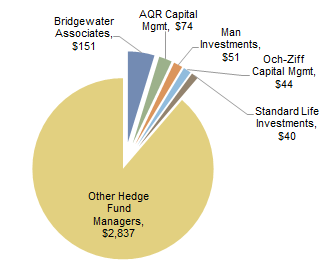

With the hedge fund industry managing an estimated $2.8 trillion in assets according to Hedge Fund Research, Inc., up from $2.1 trillion in 2007, it is true that hedge funds have become a more significant part of the marketplace. However, the hedge fund market is still just a fraction of the size of the estimated $37 trillion invested in mutual funds globally. One distinction between hedge funds and mutual funds from a systemic risk perspective is the ability of hedge funds to use leverage, which arguably creates the potential for these funds to have an outsized impact on financial markets relative to their size. In addition, assets are concentrated with the largest fund managers—by some estimates the top 20 managers control about 20% of hedge fund assets, and the top five firms a significant proportion of that.

AUM of Five Largest Hedge Fund Managers versus Total Hedge Fund Industry

As of December 31, 2015 • US Dollar (billions)

Source: Preqin.

Managers of large funds are already required to report extensive portfolio-related data on Form PF. See our February 2015 Quarterly Regulatory Update for more on the Form.

In the FSOC’s turn to hedge funds, it tasked a working group with looking closely at hedge funds including: sufficiency of available data, counterparty exposure, investment strategies, and standards for measuring leverage. One issue the FSOC specifically highlighted was the potential impact of the largest and most highly leveraged hedge fund managers on financial markets. While hedge fund managers are much more regulated today than in the pre-Dodd-Frank era, the types of strategies engaged in by hedge funds and their risk levels have largely been untouched by regulators. With regulators having pivoted toward focusing on the risks posed by activities rather than specific asset managers, one might ask whether this trend will continue as they look at the hedge fund industry.

Scrutiny of Private Investments Expanding

Fee disclosure norms still developing

A quarter rarely seems to go by without a regulator announcing initiatives or enforcement actions regarding some aspect of the private funds market. Recently, the co-heads of the SEC’s private funds unit highlighted a growing focus on private debt funds. The regulators pointed out that issues like fee and expense disclosure, liquidity, and conflicts are on the radar for these funds, as with private equity partnerships. For large private investment firms that offer debt and equity funds, investors should expect to see increased disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Industry observers also note that fee practices for debt funds are different than for private equity funds, and may involve a higher transactional fee paid to the manager and not back to the fund. This is a distinction between private debt funds and private equity funds that may require different types of disclosure to satisfy regulatory scrutiny.

In the meantime, private equity industry investor trade group Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) released the first version of what it hopes will become an industry standard fee reporting template.[1]Institutional Limited Partners Association Fee Reporting Template Version 1.0, January 2016. The template, which was developed in consultation with both limited partners (LPs) and general partners (GPs), seeks to capture both the costs to LPs of investing in a fund, and the GPs’ sources of economic return related to managing the fund. ILPA’s approach should simplify the complex task of unbundling the many potential sources of economic benefit for private fund managers and will allow investors to better assess fund economics. While ILPA’s work represents an advancement, these consistency-in-reporting issues tend to be complex to resolve. Ultimately, values reported in the ILPA template will be affected by definitions used in individual funds’ limited partnership agreements. Thus, LPs will still need to be familiar with their funds’ approaches to effectively compare costs and economics across managers.

Fee disclosure norms are still being developed in the private fund industry. ILPA’s release noted that GPs may need to make significant changes to their tracking processes and reporting procedures to provide the level of disclosure in the new template. ILPA also noted that some GPs may have difficulty providing the standardized level of disclosure for existing funds in the near term as they adjust their internal processes to capture required data. Industry commentators have already begun to suggest that GPs review their disclosure policies against the ILPA format. Those managers unable to meet the new standards may find themselves at risk for more scrutiny by investors and, potentially, regulators.

Sun Capital Decision Reverberates

Private funds held liable for portfolio company pension obligations

In a controversial decision, a US federal court recently ruled that two private equity funds were liable for a portion of the pension plan liabilities of a bankrupt portfolio company. In Sun Capital Partners III, LP v. New England Teamsters & Trucking Industry Pension Fund (“Sun Capital”) the court found that the funds were engaged in a “trade or business” and were under “common control” with their portfolio company, and thus were statutorily required to pay the portfolio company’s pension obligation. Generally, funds are thought of as passive investors (and not engaged in a “trade or business”), but the court in Sun Capital focused on the use of management fee offsets and carry forwards. In this case, each fund’s management fee was reduced to the extent that the fund manager received fees from the portfolio company for management services, which the court viewed as indicating the funds were not simply passive investors.

The two investing funds used a limited liability company to hold their ownership interest in the portfolio company—a typical structure. The funds individually did not own 80% of the portfolio company—the threshold for “controlling interest” under ERISA. However, the Sun Capital court looked upon the funds’ joint activities pre-investment (among other factors) to support its finding that the funds had formed a “partnership in fact” that controlled both the portfolio company and the joint LLC. By finding that the funds had formed a partnership outside of the LLC, the court was able to aggregate the two funds’ holdings into a controlling interest in the portfolio company.

While the Sun Capital decision is certainly fact specific, commentators have pointed out that this case may have implications for other funds, especially since the terms and structures employed are common. The pension in Sun Capital was a multi-employer plan (and thus subject to its own set of rules), but the same principles could be applied to other pension and defined contribution plan obligations. Sun Capital also raises questions about whether funds involved in club deals would be treated, in effect, as partners rather than as separate legal entities for purposes of determining pension liabilities. While the Sun Capital decision is often described as controversial and thus may not signal a broader legal shift, it does create some additional risk for investors, especially in situations that might involve portfolio company–level liabilities. Time will tell whether the decision will gain traction in other districts or whether counsel will develop other structures to reduce potential liabilities.

Regulatory Harmony Remains Elusive

EU-based MiFID II could one-up US regulations, while within the EU a proposal advances to harmonize regulations on loan origination funds

As the landmark US Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act approaches its sixth anniversary, EU- and US-based managers alike have another comprehensive piece of regulation looming on the horizon—Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II). This EU-based regulation stands to have an impact on costs in the investment management business, including for managers based outside EU jurisdiction. The good news? Regulators have pushed back compliance deadlines by one year, to January 2018. Market participants expect to see implementing regulations promulgated throughout the year this year, giving them a bit more time to evaluate MiFID’s impact on their businesses and to build out new compliance functions.

MiFID II is a comprehensive regulation. It affects trading activities in a much wider range of instruments than Dodd-Frank (which focused on trading in OTC derivatives), including equities, bonds, and derivatives; establishes new trading venues; mandates expanded pre- and post-trade reporting; and requires registration of a broader range of market participants.

Importantly, MiFID II will apply to many market participants including US-based asset managers with EU-based clients, entities that trade with EU counterparties, or those investing in securities trading on EU venues. Industry sources also point out that compliance burdens could spread beyond that initial cohort as some EU jurisdictions may seek to “gold plate” their regulations by extending some MiFID II requirements to broader classes of managers, including UCITS management firms or alternative investment fund managers that do not manage discretionary accounts.

MiFID II also takes aim at business conduct and requires that firms provide better disclosure around trade execution costs (including providing documentation that clients have received “best execution”) and “unbundle” trading costs and costs for third party investment research. These requirements differ from and are more granular than US regulation. As a result, for firms operating globally, MiFID II’s mandates may become the defining standard for managers’ internal data collection and documentation systems. Ultimately, this will create cost barriers for management firms seeking to enter the EU market. And, of course, the regulation increases compliance costs and complexity for firms operating in the EU marketplace. Perhaps good news once again for managers with scale and outsourced compliance firms.

While MiFID II is not in sync with US regulations, regulators within the European Union are aiming for more harmony within the union. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) recently issued an opinion on moving toward a harmonized approach to loan origination funds across the EU, coinciding with renewed investor interest in distressed and lending strategies. ESMA’s opinion follows the European Commission’s September 2015 “Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union,” which identified “promoting diversified sources of financing to reduce dependency on bank loans” as a regulatory priority.

Regulatory authorities have acknowledged that non-bank lenders may become important players in filling the gap left by retrenching banks. This is especially the case in the European Union, where banks have historically provided more than 50% of corporate credit. Although several European member states have specific requirements for loan origination funds, the rules vary significantly from country to country.[2]Jurisdictions vary in terms of imposition of leverage limits, permitted fund structures, diversification requirements and the ability to invest in anything other than loans. By leveling the playing field across the EU, regulators hope to promote what could become an important source of corporate credit. For managers, any new, harmonized regulation may offer welcome simplicity for operations within the 28 EU member states. Further movement on this topic is expected this year.

Footnotes