Determining the appropriate size of near-term reserves and how to invest any remaining reserves is more art than science and requires careful consideration of a number of factors

- Sizing near-term reserve funds should be guided by analysis of cash flows, endowment reliance, available liquidity, and capital needs. Any reserve funds not needed in the near term can be considered longer-term capital.

- When investing reserves as long-term capital, institutions should consider the policies needed to support responsible reserve fund management, how compatible the funds invested together are, and whether such investments will jeopardize the long-term investment pool

“Right-sizing” reserves is challenging for many institutions, given the variety of ways in which such reserves can be classified, used, and invested. Virtually all endowed institutions have operating reserves, whether termed working capital, operating funds, depreciation reserves, stabilization funds, or any number of other names. Whatever named, reserves are assets that can provide working capital; fund operations, strategic plans, or capital initiatives; and/or serve as an inexplicit buffer for endowment volatility or operating revenue shortfalls.[1]Reserves differ from liquidity. Reserves are specific sets of assets that serve some or all of the purposes listed, while liquidity reflects capital available across multiple pockets of the … Continue reading

In this research note we explore the factors institutions should consider in determining the appropriate size for their near-term reserve (i.e., readily available assets to fund shortfalls and emergencies). Reserves not earmarked for near-term purposes can be invested alongside the long-term investment pool (LTIP) to earn returns that will further support the institution. We share results from our modeling that illustrate the risks and rewards institutions will need to consider when investing reserves as long-term capital. Finally, we highlight the policies institutions will need to effectively manage their reserve investments, and we discuss some of the challenges of investing reserves alongside the endowment in the LTIP.

Right-Sizing Readily Available Reserves

No universal formula generates a perfect answer for the size of near-term reserve funds needed at a given institution. The right size reflects specific institutional conditions. In contrast, where operations and funding sources are robust and resilient to market risks, an institution does not need substantial near-term reserves. Where operating and capital funding sources fluctuate, having capital at hand to fund shortfalls and emergencies is more important. In all cases, right-sizing should be guided by analysis of plausible stress scenarios. A thoughtful financial planning exercise informs reserve requirements and, in some places, policies. Questions institutions should ask as they look to right-size reserves include:

- What will cash flows from core operations be? Core operations are mission specific. Institutions should determine the revenues and expenses from core operations, which are before subsidies from endowment and operating gifts. By treating core operating results separately when analyzing reserve requirements, an institution can identify areas subject to competitive pressures within the markets for service activities that are part of their mission, such as education, research, and program delivery. Where projections suggest core operations will perform strongly, less may be needed in near-term reserves, and where core operations are challenged, institutions may wish to add to their near-term funds.

- How sturdy are endowment distributions and gifts? Is the institution particularly reliant on endowment distributions and annual gifts to fund operations? If so, these revenues are often correlated. Can the enterprise withstand a decline in these subsidies, or should a contingency be in place to backstop potential declines? Institutions should model scenarios that project endowment spending and gifts in the event of a market downturn, and consider their reserve requirements accordingly.

- How much liquidity is available? Working capital requirements can be met by reserves or by external access to liquidity, such as a line of credit or taxable debt. Other reserves may be available to fund particular areas of need. An understanding of all the resources the institution has to generate liquidity can inform the size of near-term reserves.

- What are the plans for institutional capital? How does the institution fund capital replacement, improvements, and additions? Is the physical plant in good condition, or does it need urgent repairs? Does the institution have funding mechanisms for capital investments such as capex reserves, debt financing, and gifts? Having a good understanding of needs for the physical plant and other capital goals and how those relate to reserve funds will help institutions right-size their reserves.

Taken together, the information and analysis gathered from asking these questions should bring the institution to a place where it can identify the right size of the near-term reserve pool. What should be done with the remaining funds in the reserve? They can be considered longer-term capital and marked for investing alongside the LTIP, a strategy that may allow the institution to improve returns relative to holding substantial assets in cash or other short-term instruments that provide low to no return. However, as institutions look to maximize the contributions of available capital toward mission-related activities, the lure of long-term returns should be balanced with the realities of long-term investing. If reserve funds are called upon in the near term, the downside could outweigh the upside for both the reserves and the long-term portfolio that is in place to preserve and grow the institution’s endowment funds. In the next section, we use an example institution to illustrate some of the factors institutional fiduciaries should consider when investing their reserves (or a portion of them) in the LTIP.

Modeling the Risks and Rewards

Sample Institute has a $1.5 billion endowment and $85 million of reserve funds. The reserve level approximates one year of endowment distribution, which funds approximately 10% of the institution’s operating budget. This institution currently achieves positive operating margins, but certain programs are sputtering and staff are concerned that operations will result in a deficit in the near future. For the purpose of this analysis, we model a stressed example, where Sample Institute invests all of its reserves alongside the endowment in the LTIP and needs to use these reserves to backstop slumping operating results.

Using the Cambridge Associates portfolio/enterprise risk model,[2]The model projects an institution’s operating results (“bottom line”) given various asset allocations or investment risk profiles, various spending rules, and various capital market scenarios. … Continue reading we consider five years of projected operating results and portfolio performance in two different market scenarios:

- A return to normal scenario, where the portfolio achieves positive, but muted, returns.

- A negative market scenario, where the portfolio return is negative for each of the modeled years, illustrating the impact of a market downturn and loss of market value.[3]In the return to normal scenario, we incorporate current valuations and assume equity valuations revert to fair value over ten years. This scenario makes assumptions about the market environment … Continue reading

The model helps us assess the relationship between the assets and the enterprise, and informs the decisions about investing reserves in the LTIP. Specifically, we assess the effects on:

- Enterprise operating results,

- Reserve balances, and

- Performance and liquidity of the LTIP.

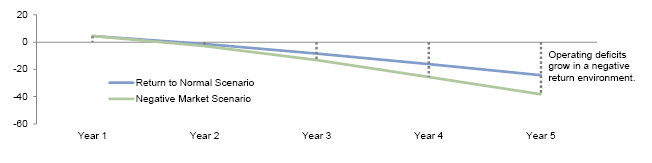

Enterprise Operating Results. Sample Institute is bracing for operating deficits. The gap between operating revenue and expenses widens in the negative market scenario, because a declining endowment market value results in a lower endowment distribution to operations (Figure 1).[4]Our model assumes a spending policy of 5% of average market value over three prior years. A constant growth rule may not respond as quickly to a market value decline unless a market value cap on … Continue reading This creates a greater demand for subsidy from reserve funds or other possible sources of liquidity.

Figure 1. Stress Testing Operating Revenues and Expenses: Operating Surplus/Deficit in Two Return Scenarios

US Dollar (Millions)

Source: Cambridge Associates portfolio enterprise/risk model.

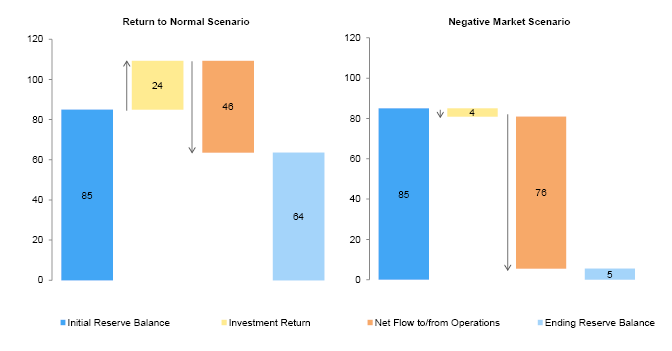

Reserve Balances. Positive investment performance in the LTIP over time will grow the reserve funds to higher levels than they would achieve in cash or cash-like instruments or even intermediate-term bonds. In the return to normal scenario, the $24 million from investment returns adds to the starting value of $85 million in reserves, and offsets some of the $46 million withdrawn to fund operations (Figure 2). However, even though diversified portfolios outperform in the long term, in shorter periods institutions must not forget that investments can decline. In the negative market scenario Sample Institute’s investment losses compound with reserve withdrawals to contribute to a rapidly declining reserve balance.

Source: Cambridge Associates portfolio enterprise/risk model.

The negative market scenario illustrates the links between the enterprise, reserves, and endowment. Reserves are nearly depleted over the five-year period because of the combined impact of investment losses and greater withdrawals required to fill deeper gaps in operating revenue when the endowment market value and its distributions to operations decline. This scenario reminds institutions that investing reserves in the LTIP is not a “free lunch,” particularly when all reserves are invested and withdrawals are required.

Performance and Liquidity of the LTIP. Reserve funds can grow with positive investment performance and decline with losses, but institutions should also think through the implications invested reserves present for the endowment funds that represent the bulk of the LTIP. If reserve funds are needed to fund operating deficits, how will those withdrawals from the portfolio affect the remaining investments? Would the LTIP have been better off had the needed reserves not been invested?

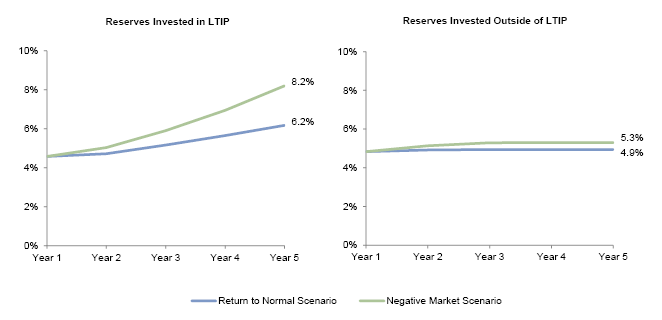

When reserves are invested in the portfolio and withdrawn, the LTIP’s exit rate[5]Exit rate equals the total annual withdrawals from the LTIP divided by the beginning-of-the-year market value. In the Cambridge Associates Annual Pool Returns Survey, we collect this information and … Continue reading exceeds the endowment’s spending policy rate, because the exit rate reflects all the withdrawals from the portfolio. Sample Institute’s endowment spending policy is 5% of the average endowment market value of prior three years, but the LTIP’s exit rate climbs to 6.2% in the return to normal scenario and to nearly 8.2% in year five of the negative market scenario (Figure 3). What if the Institute had not invested its reserves in the LTIP? In both return scenarios, exit rates are lower for the LTIP and much closer to the endowment spending policy. The higher exit rate in the negative market scenario reflects the declining market value in the denominator.

Source: Cambridge Associates portfolio enterprise/risk model.

For more detail on the net flow rate, see Ann Bennett Spence, Tracy Filosa, and Billy Prout, “The Missing Metric for Endowment Growth: Net Flow Rate,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, November 2014.

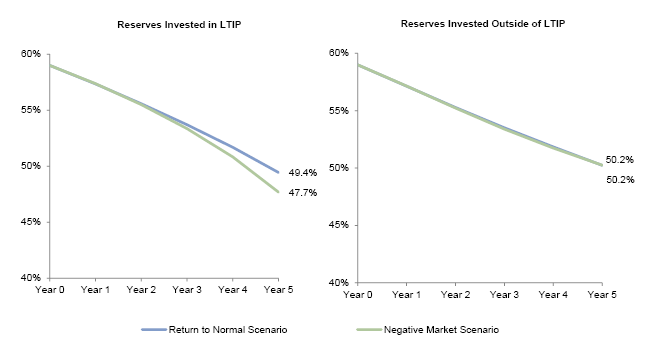

When reserves are invested in the LTIP and withdrawn, their withdrawals have a material impact on the liquidity of the remaining portfolio.[6]The Cambridge Associates portfolio/enterprise risk model evaluates liquidity by asset class categories. The model designates asset classes as liquid (e.g., equities and bonds), semi-liquid (e.g., … Continue reading The withdrawals from the portfolio come from the most liquid investments, so this component declines as a portion of the entire portfolio. The withdrawals for Sample Institute outpace any additions that may come from investment returns, capital distributions from private investments, or gifts to the endowment.[7]New gifts to the endowment are assumed to be $0 in our case study. Endowment gifts could offset some outflows from endowment. This is the impact of a portfolio’s net flow rate: the regular payout … Continue reading We call this the liquidity sacrifice. For the Sample Institute, both of our scenarios result in some portfolio liquidity sacrifice, whether reserves are invested in the LTIP or not (Figure 4). The liquidity sacrifice is greatest in the negative market scenario where the reserves are invested in the LTIP and the exit rate is highest.

Source: Cambridge Associates portfolio enterprise/risk model.

Did Sample Institute’s decision to invest reserves in the LTIP jeopardize the endowment funds in the LTIP?

- When returns are positive, endowment funds are only moderately impacted by the reserves invested alongside, as reserve withdrawals reduce the liquidity of the overall portfolio.

- In the negative market scenario the impact on the endowment funds is more pronounced, because the reserve investments increase the LTIP’s challenges. The significant withdrawals from the portfolio may require asset sales at market low prices, exacerbating losses and hampering recovery when markets rebound to positive territory. The lower portfolio liquidity also may limit buying and rebalancing opportunities.

This analysis assumes that the LTIP’s investment profile/policy does not change when reserves are invested alongside the LTIP. This approach may not be feasible or advantageous when investing reserve funds, depending on their exact profile and how large they are within the LTIP. As this analysis shows, if reserves will be tapped more during downturns and constitute a meaningful portion of the LTIP, the investment committee should consider adjusting investment policy and portfolio structure to better reflect the goals and needs of all the assets in the LTIP.

Considerations for Investing Reserves

When investing reserves in the LTIP, institutions should consider what policies are needed to support responsible reserve fund management, how compatible the funds invested together in the LTIP are, and whether investing reserves will jeopardize the LTIP, as they did in the negative market scenario for Sample Institute. Forethought and consistent responses can improve the chances of investment success for the reserves and endowment assets in the portfolio.

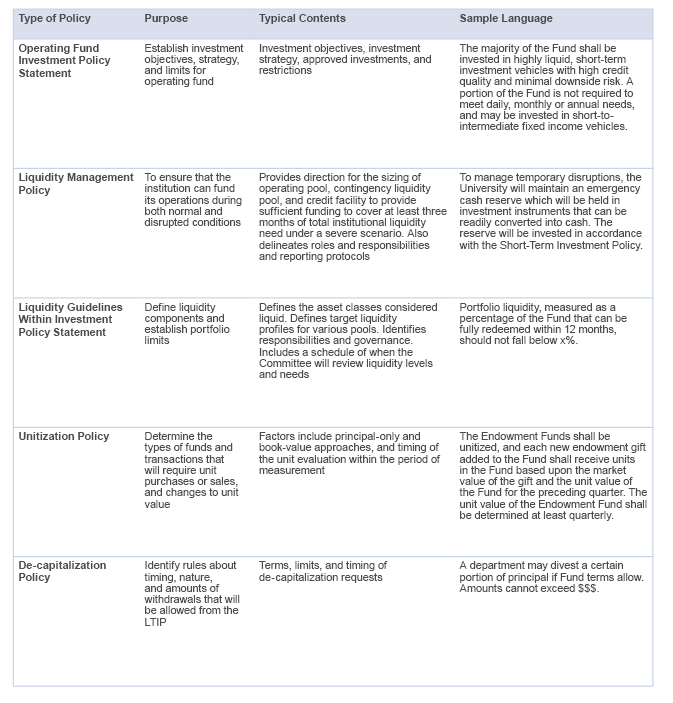

What policies should be in place to support responsible reserve fund management and investment? Institutions should consider establishing policies that document the investment objectives for the operating fund, determine the types of funds and transactions that will require unit sales or purchases, and identify rules about timing, nature, and amounts of withdrawals from the LTIP. In addition, institutions should review the liquidity guidelines within their investment policy statement (IPS) and ensure they have a liquidity management policy. Figure 5 summarizes the six key policies institutions should consider.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

How compatible are the funds invested together in the LTIP? While the LTIP can accommodate some diversity between endowment funds and reserves, drastic differences can undermine the long-term investment strategy. Compatibility among assets in the LTIP can be evaluated with the guidance of a robust IPS. The distribution policy and the target asset allocation outlined in the IPS will be most revealing.

To implement a shared investment policy, the institution will need to understand:

- Will the funds share similar inflow and outflow (net flow) rates?

- Does a common de-capitalization policy satisfy short-term needs and long-term investments?

- Do the funds share a similar risk profile and investment time horizon?

Do reserve funds in the LTIP jeopardize the long-term goals for endowment assets? The primary role of the LTIP is to preserve and grow the permanent endowment assets in perpetuity. The optimal investment strategy for endowment assets should be considered before the LTIP becomes a vehicle for other institutional capital–like reserves. The following questions help determine whether additional capital will augment endowment funds or weaken them:

- Do portfolio administration requirements (unitization, accounting, etc.) become overly complex and burdensome?

- Does the portfolio deviate from a long-term orientation and/or become de-risked (to an extent) to accommodate shorter-term assets or funds with larger and lumpier distribution requirements?

- Do withdrawals from the LTIP require undesirable asset sales or liquidity sacrifices for the funds that remain?

Conclusion

Sizing reserves appropriately is more art than science, and institutions have a number of factors to consider when sizing their near-term reserve pool, including operating projections, gifts and endowment, sources of available liquidity, and capital plans. After determining the appropriate near-term reserve size, an institution may discover more funds in its reserves than needed. Such funds can be invested alongside the LTIP to earn returns that will further support the institution. However, as we have shown, the decision to invest reserves with the LTIP is not a simple one. Modeling returns under different scenarios using a tool like the Cambridge Associates portfolio/enterprise risk model can help institutions understand whether their extra reserves can truly function as long-term capital. When this is the case, reserve funds can be invested in the LTIP, expanding the value of institutional resources, and contributing to the mission and the long-term financial health of the institution.

Tracy Filosa, Senior Investment Director

Sarah McIntosh, Associate Investment Director

Kelsey Sommers, Investment Associate

Footnotes