Bond yields have fallen to extreme levels in 2016, with rate cuts and asset purchases by central banks playing a major role. Whether this intense monetary policy is working as intended is hotly debated; data on inflation and growth has been mixed in regions like the Eurozone and Japan, but might have been even worse in the absence of such efforts.

Please see Wade O’Brien et al., “Feeling Negative About Sub-Zero Interest Rates,” Cambridge Associates Research Brief, March 25, 2016.

Putting aside the questions about economic impacts, we have been concerned about the consequences of low rates on investors for some time. Low yields will imperil future returns for a variety of asset classes and create problems for firms like insurance companies and those with significant pension obligations. Interest rates are unlikely to sharply increase from today’s levels, though central bankers and investors are increasingly questioning the usefulness of more easing. Investors should understand how low rates have distorted both markets and company fundamentals and be prepared to take action if policymakers signal a shift in strategy.

Low Yields and High Asset Prices

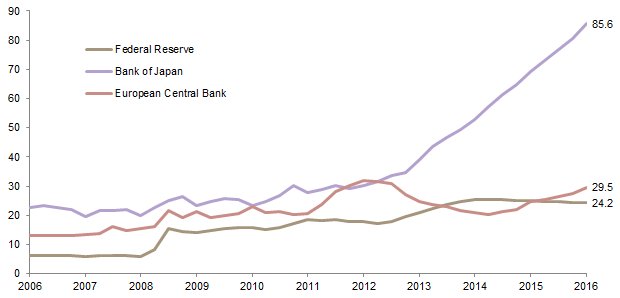

Quantitative easing efforts by central banks continue to push new boundaries. The Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) balance sheet has now swollen to ¥453 trillion in assets, while the European Central Bank (ECB) has been buying €80 billion a month (!) of assets and now owns around €3.4 trillion. Purchases have mainly been focused on sovereign bonds, but in a growing number of jurisdictions, central banks are also buying corporate bonds (and in some cases, equities). The volume of purchases is creating a shortage of eligible collateral—an astonishing fact obscuring that sovereign debt levels remain at or near historical highs. The BOJ already owns over 35% of outstanding Japanese government bonds and faces competition from banks and insurance companies that need to park their cash somewhere; the ECB owns roughly half this ratio but its massive purchases mean it will buy the equivalent of all net sovereign bond issuance this year by Eurozone governments.

Sources: Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Eurostat, Federal Reserve, Japan Cabinet Office, Thomson Reuters Datastream, and US Department of Commerce – Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Notes: GDP data are annualized figures reported on a quarterly basis. Central bank assets represent balance sheet values as of quarter-end.

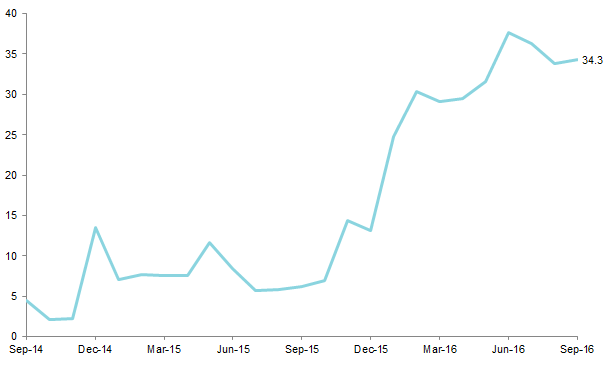

These asset purchases and cuts to benchmark interest rates have caused yields to steadily decline across developed and emerging sovereign bond markets since the start of 2016. The BOJ was first to embrace negative rates in January, and the ECB followed suit in March. Investors now must travel far out on the yield curve in these markets to pick up even a smidgen of carry; ten-year government bonds from both Germany and Japan featured sub-zero yields at the end of September. Globally, an astounding 34% of developed market sovereign bonds have negative interest rates, including around 80% of German equivalents and almost all Swiss government bonds. While the US Federal Reserve Bank actually hiked its main reference rate last December (to a still modest 0.375%) and has been out of the bond-buying business for some time, yields on US Treasuries have fallen this year as global investors cast their nets wider in a desperate hunt for assets with positive carry.

Rise of Negative Yielding Global Treasury Bonds

September 30, 2014 – September 30, 2016 • Percent of Total Market Value (%)

Sources: Barclays and Bloomberg L.P.

Notes: As of September 30, 2016, the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Treasury Bond Index held a market value of $26.4 trillion, $9.1 trillion (34%) of which carry a negative yield. The Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Treasury Bond index only contains bonds with maturities greater than one year.

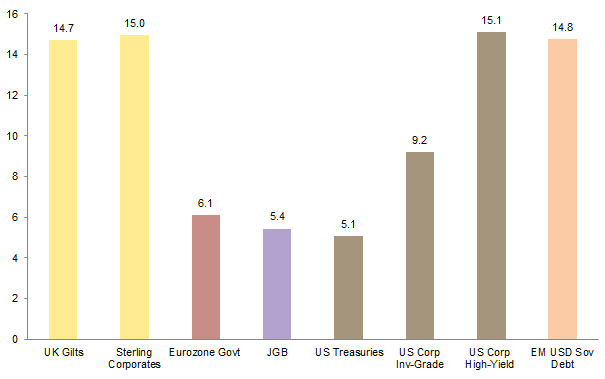

Low sovereign yields have in turn pulled down yields on many types of credit instruments, generating gains for bond investors. Some of the biggest gains have been in the United Kingdom, where yields on gilts plunged following the “Brexit” vote (and hints of a rate cut); the J.P. Morgan Gilt Index has returned nearly 15% year-to-date. Returns for higher-quality bonds in other regions have been respectable but lower, given starting yields. This will likely be the case for some time; euro-denominated investment-grade and high-yield bonds yielded just 0.66% and 4.03%, respectively, at the end of September.

Sources: Barclays, Bloomberg L.P., J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Performance based on total returns in local currency, except for emerging markets debt, which is denominated in US dollars. “UK Gilts” represented by the J.P. Morgan UK Government Bond Index; “Sterling Corporates” represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Sterling Aggregate Corporate Bond Index; “Eurozone Govt” represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Euro Government Bond Index; “JGB” represented by the J.P. Morgan Japan Government Bond Index; “US Treasuries” represented by the Bloomberg Barclays US Treasury Bond Index; “US Corp Inv-Grade” represented by the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Bond Index; “US Corp High-Yield” represented by the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High-Yield Bond Index; “EM USD Sov Debt” represented by the J.P. Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Bond Index.

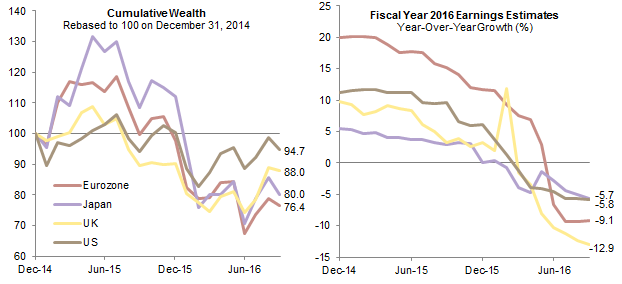

Higher-yielding fixed income asset classes like US high-yield bonds and emerging markets debt have also posted large gains in 2016 despite weakening fundamentals. Similar dynamics have played out in equity markets, where despite weak earnings growth (and high valuations in US equities), analysts have justified higher prices due in part to lower discount rates. Other beneficiaries from low rates include real estate (given the impact of lower financing costs and discount rates); some previously dovish members of the Federal Open Market Committee have specifically cited frothy conditions in property markets when making the case for tighter monetary policy in recent months.

What, Exactly, Do Low Rates Accomplish, Anyway?

Policymakers rationalized the move to low (and eventually negative) interest rates with arguments about their direct and indirect benefits for growth and inflation. Yet for the most part these policies have disappointed—both because the economic landscape has proven more challenging than expected and because of unintended consequences.

One argument was that lower borrowing costs would encourage companies to take on debt and expand capacity, in turn boosting employment. Seemingly overlooked in this line of thinking were the circumstances of corporate executives and their bankers. Facing lackluster demand and excess capacity in some industries, many companies in countries with negative rates have not been tempted to borrow. For example, despite near-zero borrowing costs, outstanding lending to Eurozone companies has continued to shrink for much of the past 18 months, and capital expenditure spending, while improving, remains below pre-crisis levels. Trends in Japanese investment had been more encouraging (as had their trend in rising profitability), but these companies were already cash rich and thus had little need for financing.

The willingness of banks (as opposed to investors via the capital markets) to play a role in expanding the supply of credit has been hindered by the way low rates have combined with increased regulatory demands to make lending less lucrative. Yields on loans have dropped while funding costs have proven stickier, reducing net interest margins for banks. While mark-to-market gains on existing assets and other dynamics may previously have masked the impact of low rates on profits, evidence is growing that payback is around the corner. Earnings expectations are falling for banks across developed markets, weighing on share prices. Quantifying the impact of falling rates is an inexact science and depends on many factors, but in one exercise Citibank estimated that every 10 basis points of rate cuts by the Bank of England will trim earnings per share by 1%–2% for the largest UK banks.

Sources: I/B/E/S, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Cumulative wealth data are based on total returns net of dividend taxes. All data are monthly and in local currency terms. Earnings for Japan are estimated for fiscal year ending March 31, 2017.

Record-setting bond issuance volume in 2016 suggests that borrowers have options other than bank loans, but the central bank purchases supporting these markets may be introducing new problems. Weakening sovereign and corporate credit fundamentals suggest investors are becoming less discriminating, increasing the likelihood of future problems. This may be a slow-burning fuse for some sovereigns (though Japanese debt-to-GDP at 250% already looks quite worrying), but problems could crop up more quickly for companies. Leverage ratios for US non-financial investment-grade companies have soared from around 1.6 times to around 2.3 times trailing 12-month EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization), in part because companies with weak profits are borrowing to fund dividends and share buybacks. More cautious (and parsimonious) European companies have seen fundamentals deteriorate more slowly, with current leverage rising to about 1.4 times. The story is similar but more pronounced for high-yield companies, though here the picture excluding commodity companies looks much better.

Low (and in some cases, negative) interest rates were intended to boost household and corporate spending by lowering their debt servicing cost. This boost has not materialized in many countries for a variety of reasons. Lower interest rates reduce income for savers, an especially large problem in aging economies—52% of Japanese household assets are in the form of cash and bank deposits, more than three times the equivalent percentage in the United States. This may help explain why Japanese consumer spending is still below the levels seen when Abenomics was first implemented, while US consumption in recent years has risen faster and, in fact, has been the only leg supporting the US recovery. The ratio of assets to liabilities also comes into play; even for equity and mutual fund–rich US households, the value of their savings accounts and other short-term investments (and thus their foregone interest) dwarfs the amount of liabilities.

Adverse Consequences for Investors

Weakening credit fundamentals and inflated equity valuations are generalized problems for all investors, but some are feeling even more pronounced stress. While insurance companies offer a variety of products, and thus the exact impact of lower rates will vary depending on their business mix, several things are clear. One is that because insurance companies tend to have much longer duration liabilities than assets, decreases in rates have a disproportionately negative impact on their solvency levels.[1]For more on this, see European Central Bank, “Financial Stability Review,” November 2015. Two, because insurance companies need to reinvest premiums during a period of declining rates in investments that are generating lower and lower amounts of yield, the impact on profitability and solvency can be drawn out. Estimates of the amount of foregone interest income for European and US insurance companies from lower yields are staggering—one from the Institute of International Finance recently put it at nearly half a trillion US dollars since 2008.[2]Hung Tran et al., “Capital Markets Monitor,” Institue of International Finance, September 2016. Insurance firms have various tools to try to respond (raising premiums where possible, moving into more aggressive investments, etc.) but these can entail new potential problems. Circling back to unintended consequences and citing one example, the eight million Americans who are seeing premiums soar on their long-term care policies will in many cases divert funds from other uses like consumption, weighing on economic growth.[3]For more detail on this, see Leslie Scism, “Low Rates Are Tormenting Insurers—and Their Customers,” The Wall Street Journal, March 20, 2016.

Pension funds face similar issues, as they typically use a discount rate like the yield on AA-rated corporate bonds to help value future liabilities. As these rates have fallen, huge holes have opened up in their balance sheets. According to Citigroup, Eurozone corporate yields have fallen in half (from 4% to 2%) over just the past four years. Citigroup estimates that the total value of unfunded corporate pension obligations stands at $403 billion and £84 billion for the S&P 500 and FTSE® 350, respectively. Looking at the total of unfunded and underfunded government defined benefit plans across OECD countries, the sum may reach a staggering $78 trillion.[4]Farooq Hanif et al., “The Coming Pension Crisis,” Citigroup, March 2016. This is a multi-faceted problem and many other drivers are at work (longevity, contributions, asset returns, etc.) but lower discount rates play a role. This problem is not abstract for investors; as companies with pension plans put more aside for future obligations, profitability and spending will be impacted.

The Bottom Line

Low rates are a symptom as much as a cause of slow growth. In rushing to solve today’s problems, policymakers may be sowing the seeds for even larger ones down the road. Negative rates have had a host of consequences, including: (1) pushing investors toward more aggressive investments despite weakening credit and equity fundamentals; (2) tempting companies, which see little reason to borrow to fund future growth, to use leverage to try to boost returns on equity and other metrics; (3) reducing the interest income of savers and hurting consumption; (4) eroding the profitability of banks and insurance companies; and (5) pushing pension plans onto increasingly shaky ground. A growing recognition of these consequences seems to have moved central bankers to press the pause button on lower rates in recent months. It will take even more courage for them to begin to reverse what are unprecedented interventions in bond and other markets. While such a step would undoubtedly trigger significant short-term volatility, it could ultimately clear the deck for more promising investment opportunities.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Stuart Brown, Investment Associate

Footnotes